Monday – Memorial Day

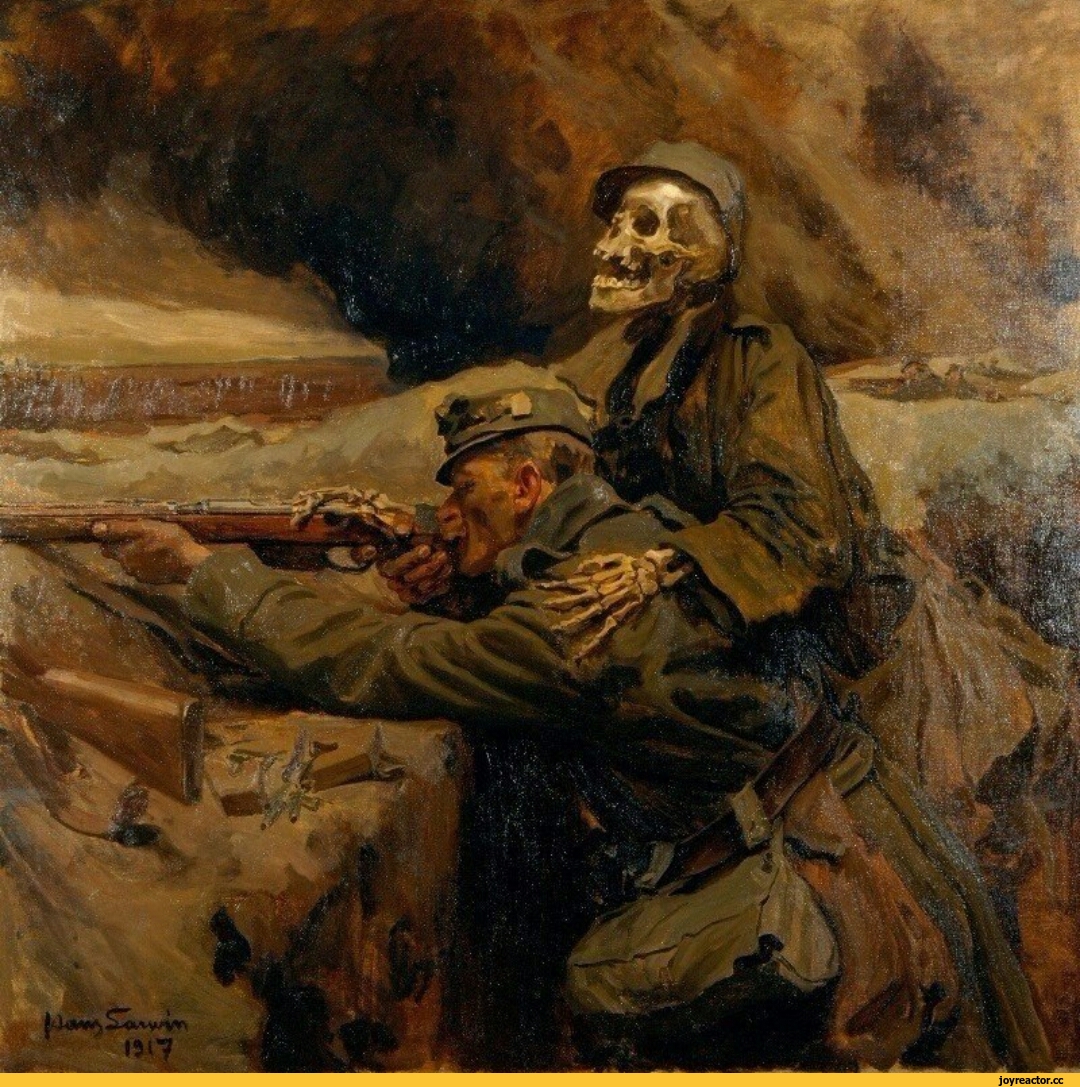

I’ve just discovered the poetry of Charles Hamilton Sorley, a World War I poet who died at 20 in the Battle of Loos (1915) and who anticipated the searing anti-war poetry of Wilfred Owen. Like Owen, Sorley is a far better poet than the romantic Rupert Brooke to honor our war dead since those deaths will be in vain if we romanticize them. Our challenge is to learn from them so that future soldiers will not die in meaningless wars.

I mention Brooke only because I’ve just come across a reference to him in May Sarton’s Magnificent Spinster (1985), which I’m currently reading. As World War I rages, the teenage protagonist at first embraces the poet in her support of the war:

Jane, ardent, fiercely partisan on France’s and England’s side, reciting poems by Rupert Brooke as the gospel, had been swept with millions of others into a passionate rejection of everything German.

To Jane’s credit, she soon awakens to the dangers of such partisanship when she encounters the pacifism of her heretofore silent sister:

Jane was much too passionate to be naturally tolerant as Martha seemed to be. For her, tolerance had to be learned, and learned through living out strong convictions and the inevitable collisions that take place when strong conviction is confronted by reality, when a person actually lives what he or she believes. It had been a shock when quiet, gentle Martha spoke with such force about pacifism. In her heart of hearts Jane had to admit that the sister who had always chosen to stay in the background had a strength she had not suspected. And of course she had been wrong to speak so hotly against the Germans…

And on an impulse she took out her violin, tuned it, and played a Beethoven violin sonata. It would always be Jane’s instinct to do something active to solve problems.

Sorley’s poem too confronts romantic conviction with reality. I have no doubt that it also would have tempered Jane, pulling her out of her jingoistic fantasies:

When you see millions of the mouthless dead

Across your dreams in pale battalions go,

Say not soft things as other men have said,

That you’ll remember. For you need not so.

Give them not praise. For, deaf, how should they know

It is not curses heaped on each gashed head?

Nor tears. Their blind eyes see not your tears flow.

Nor honor. It is easy to be dead.

Say only this, “They are dead.” Then add thereto,

“Yet many a better one has died before.”

Then, scanning all the o’ercrowded mass, should you

Perceive one face that you loved heretofore,

It is a spook. None wears the face you knew.

Great death has made all his for evermore.

This past week I heard a memorial service sermon (for longtime friend Boo Cravens) that was powerful in the way it made a similar point. When mourning the dead, we must resist resorting too quickly to comforting metaphors, which can function as facile consolations. Before all else, we must acknowledge that “great death has made all his for evermore.”

After that, we can search for some greater meaning. But take it from a young man who grew up far too quickly and died far too young: our first task on this day is to acknowledge the horrors of war.