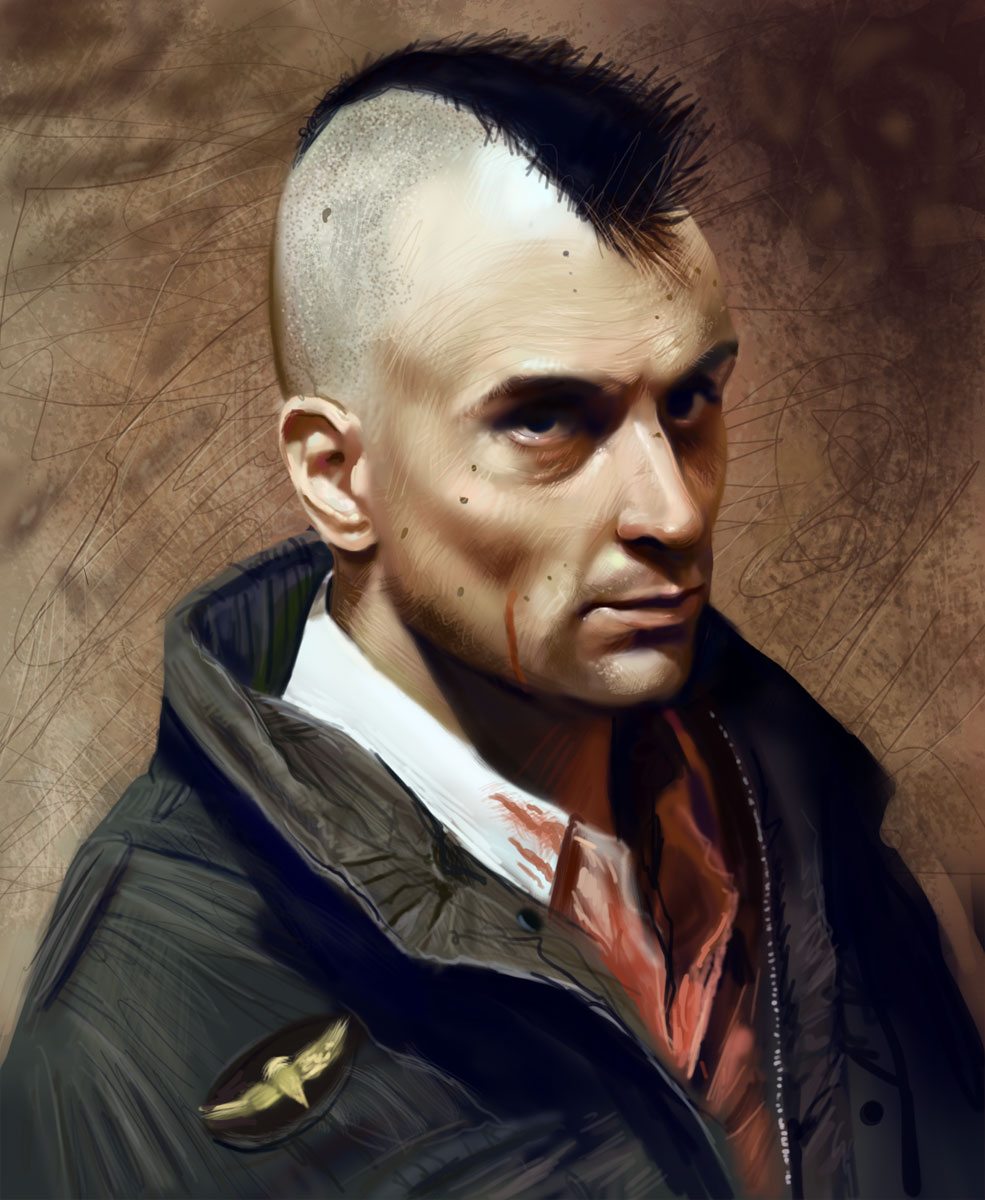

Robert DeNiro as Travis Bickle

Robert DeNiro as Travis Bickle

I continue here my discussion of three works that just happened to come together during one evening last week: John Updike’s novel Terrorist, Martin Scorcese’s film Taxi Driver, and George Bernard Shaw’s play Arms and the Man. My question is whether Shaw’s humanism is a sufficient answer to the undercurrent of American rage that Updike talks about in Terrorist and that Scorcese makes the subject of his 1976 film.

In the Scorcese film Travis Bickel (played by Robert DeNiro) becomes obsessed with urban blight and crime, the “scum” that he sees infesting America. Eventually he starts shooting people.

There were a number of vigilante movies that appeared in the 1970’s in response to all the upheavals in American society at that time. People could thrill to Charles Bronson acting out revenge fantasies (in Death Wish) and Dirty Harry/Clint Eastwood asking, “Do you feel lucky, punk?” as he points a gun that may or may not have one remaining bullet in its chamber

Scorcese’s film is a more intelligent treatment of the rage. Bickel is proclaimed a hero because he wipes out a prostitution ring and saves 12-year-old Jodie Foster. Yet it is only an accident that has him killing pimps rather than a politician. The movie would enter into John Hinckley’s thinking as he went on to in fact shoot a politician.

If Travis Bickel were driving his taxi today, I suspect he’d have his radio perpetually tuned to rightwing perpetual grievance stations. So does Shaw present an adequate response?

In the world of Shaw’s 1894 play, characters are trapped in preconceived notions of themselves and society. When something jolts them out of this stasis, however, they adjust, sometimes with good humor. Shaw seems to find everyone basically decent and open to reason. Sergius and Riana, while not wholeheartedly embracing change, recognize that their potential new partners will help them grow and so allow themselves to be pushed into marrying them.

If I seem to be mixing apples and oranges as I talk about Shaw and terrorism, allow me to explain where I’m coming from. I was raised on Shaw’s British humanism (coming as I do from a long line of British Bateses, Jacksons, Fulchers, and Scotts) and carry this background into the 21st century. Upon encountering political extremism of various sorts, I wonder if I am an archaism. How naïve is it of me to think that mutual respect and reasoned discourse across political divides is possible? Can humor keep conversation going and bridge conflict? How far can Shaw’s vision carry us?

As I look at the news these days, the challenges ahead seem daunting. An extremist might not take part in the kind of dialogue that is at the basis of Shaw’s dramas, including such hard-hitting political plays as Man and Superman, Major Barbara, and Heartbreak House. After all, entering into even contentious dialogue with another person implies a willingness to engage, however remote the possibilities of agreement.

Maybe Updike is similarly naïve when he has his Jewish guidance counselor make headway with the suicide bomber in Terrorist. Or maybe he has them talk because, without such human interaction, there can be no story. Only shouting and killing.

I know that I work in a sheltered environment that operates on the premise that reasoned discourse is key. As one who was periodically referred to as Mr. Chips by my past president, I may be rational to a fault. So am I indeed a relic of an earlier age, the English professor equivalent of Hilton’s benign and occasionally befuddled classics teacher? If so, it worries me.

That’s because I want to provide my students with the resources they need to survive, and flourish, in the world. I don’t want to be setting them up for a fall.

Literature, luckily, covers the range of human experience. There are plenty of characters acting irrationally in the stories that we rationally examine, and these stories can come to our aid in tumultuous times. So in that way it’s okay to keep doing what I’m doing.

But I need to be humble and take Shaw with a grain of salt, admiring his humanism while also viewing it with skepticism. I can teach my students to respect others and other points of view while warning them that they won’t always be respected in return. And then they can go out and learn it for themselves.