Wednesday

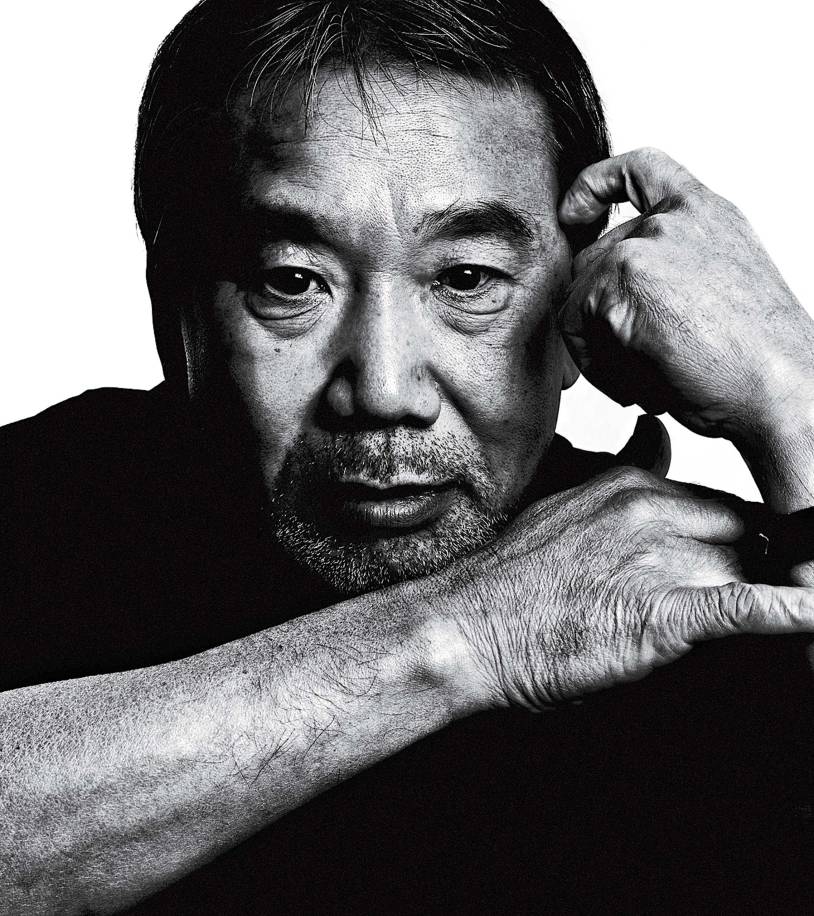

People are constantly making generalization about millennials, which is to say those born between 1982 and 2004. As a contribution to the discussion, I describe today my first year seminar “Haruki Murakami’s Existential Fantasies.” Don’t worry if you don’t know Murakami’s work as I’ll provide sufficient context. What’s important is how the students responded.

I can report that millennials aren’t much different than we were as boomers fifty years ago. They are fascinated by existentialism, as many of us were, because they are wrestling with life’s big issues, especially identity and purpose. Because of student debt and a less forgiving economic environment, they may feel more pressured about life after college than we were, but the same kinds of literary quests engage them. They find kindred souls in Murakami’s stressed-out protagonists.

Murakami’s novels work as existential parables. His protagonists begin as functionaries within a system but then break free—sometimes willingly, sometimes because they are pushed—to find more meaningful existences. Thoreau’s observation that “the mass of men lead lives of quiet desperation” summarizes the plight of many Murakami characters while his determination to “live life deliberately” becomes their quest as well. Murakami’s literary forebears are key figures in existentialism: Dostoevsky, Kafka, Camus, Raymond Carver, and hard-boiled detective novelists Dashiell Hammett and Raymond Chandler. Murakami once said in an interview, “So for me it’s the same thing, Dostoevsky and Raymond Chandler. Even now, my ideal for writing fiction is to put Dostoevsky and Chandler together in one book.”

To these western influences Murakami adds an element of Japanese fantasy, and his novels can be characterized as magical realist. To summarize the four novels we studied,

–in Wild Sheep Chase the protagonist must be jolted out of his soul-sucking job to defeat an authoritarian sheep god who wants to turn all Japanese into metaphorical sheep;

–in Hard Boiled Wonderland and the End of the World, a soulless “calcutec” must find refuge in an internal fantasy world to fight against his programming;

–in Wind-Up Bird Chronicle, the protagonist confronts the forces that are stupefying Japanese society and destroying the possibility of authentic relationships; and

–in Kafka on the Shore a 15-year-old runs away from home to escape the Oedipal destiny his emotionally abusive father has predicted for him.

In her essay on Wild Sheep Chase, Val quoted Thoreau as she talked about how the protagonist must be jolted out of his empty existence (he designs fliers advertising such items as margarine) in order to find a life that is meaningful. The protagonist must be stripped of everything familiar before he can confront his inner self. He learns at the end that he doesn’t want to live a sheep-like existence.

Genevieve took a similar approach with the novel, only in her view the protagonist is emotionally numb and must learn how to feel, which he learns how to do by connecting with nature. It’s as though the pressures of high-stress living have closed him down. Genevieve compared the novel to the movie Moonlight, where a tough environment has beaten the sensitivity out of the Chiron, who must find his way back to his humanity.

Writing about Hard Boiled Wonderland, Danielle, Cam2, and Andrew (an English, philosophy and physics major respectively) talked about how the nameless protagonist must get in touch with his shadow side (who is literally his shadow) in order to break from a life that consists entirely of work and meaningless hook-ups. Cam2 talked of his need for an authentic existence. When, in the protagonist’s fantasy world, his shadow instructs him to map the walled city in which he lives so that they can escape, his life suddenly becomes filled with potential meaning and he embarks on an adventure. Ultimately he discovers that genuine relationships, music, and writing are what make life worth living.

Seth, Olivia, and Lily all tackled Wind-Up Bird Chronicle, each from a different angle. For Seth, the novel is about how Japanese men suppress their feelings and, in the process, destroy their lives. (There is a gruesome image in the novel of a man skinned alive, which Seth said captures the fear of exposure.) The protagonist Toru tries to close his eyes to his inner anger but saves himself when he confronts it.

Olivia was interested in protagonist Toru’s marriage to Kumiko and how the forces of Japanese society are pulling them apart. Only by facing up to these forces do they salvage their relationship.

Lily was interested in a side character, a teenage girl who goes on her own identity quest. Living an aimless existence where she obsesses over death, she finally breaks with convention and goes on to live her own life.

Kafka on the Shore drew the most interest. For Rachel, the novel is about the need to leave home in order to find oneself (a classic college drama) whereas for Alexandra, a diplomat’s daughter, the drama was about 15-year-old Kafka never feeling he has a stable identity and having to forge one for himself. Eliana, an adopted Chinese orphan, was riveted by Kafka’s mother abandoning him and related to his need to construct a plausible explanation for why she did so (and to forgive her as well). Briana, an out lesbian with a trans girlfriend, was pleased to see a trans character undergoing his own identity quest. For Maia, Julia, and Cam1, the novel is about dealing with and moving past emotional childhood trauma.

As you can see, Murakami’s existential parables meant something special to each student. It helps explain why, world-wide, few authors have a bigger following amongst young people.