Thursday

Weddings can be occasions for substantive conversations, and I had such a conversation with my eldest son this past weekend when we assembled for my nephew’s wedding. Our talk touched on some of his frustrations, including my failure to initiate phone calls—he usually calls me—and his desire for more substance when we do converse.

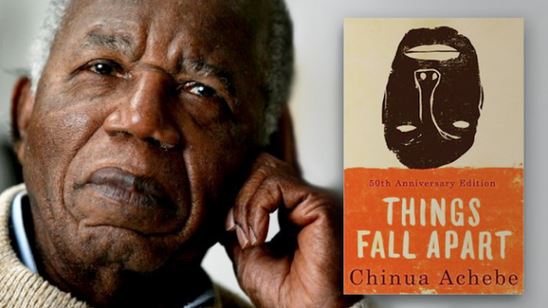

It was an important talk but, by the end, I felt like Okonkwo in Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart. Hang on while I explain.

First, I must point to an obvious contrast. Okonkwo despises his father, so much so that everything he does is motivated by his desire to prove he is different. So whereas Unoko is “lazy and improvident,” Okonkwo is a super achiever:

He had no patience with unsuccessful men. He had had no patience with his father.

Unoka, for that was his father’s name, had died ten years ago. In his day he was lazy and improvident and was quite incapable of thinking about tomorrow. If any money came his way, and it seldom did, he immediately bought gourds of palm-wine, called round his neighbors and made merry. He always said that whenever he saw a dead man’s mouth he saw the folly of not eating what one had in one’s lifetime. Unoka was, of course, a debtor, and he owed every neighbor some money, from a few cowries to quite substantial amounts.

It so happens that Unoka also dies a dishonorable death. The novel explains that he

had a bad chi or personal god, and evil fortune followed him to the grave, or rather to his death, for he had no grave. He died of the swelling which was an abomination to the earth goddess. When a man was afflicted with swelling in the stomach and the limbs he was not allowed to die in the house. He was carried to the Evil Forest and left there to die.

Throughout the novel, Okonkwo strives to be the anti-Unoka, and for a while it appears that he will succeed. Achebe notes that he is a self-made man, one who has—through dint of ambition and hard work—pulled himself up by his own bootstraps:

With a father like Unoka, Okonkwo did not have the start in life which many young men had. He neither inherited a barn nor a title, nor even a young wife. But in spite of these disadvantages, he had begun even in his father’s lifetime to lay the foundations of a prosperous future. It was slow and painful. But he threw himself into it like one possessed. And indeed he was possessed by the fear of his father’s contemptible life and shameful death.

Okonkwo’s fear of being weak like his father, however, gets him into trouble. At the end of the book, flexing his muscles, he kills one of the British colonists involved in “the pacification of the primitive tribes of the Lower Niger.” Then, realizing that the others will not join him in his rebellion, he hangs himself. Guess where suicides end up. As one of his fellow tribesmen explains to the British,

It is an abomination for a man to take his own life. It is an offense against the Earth, and a man who commits it will not be buried by his clansmen. His body is evil, and only strangers may touch it. That is why we ask your people to bring him down, because you are strangers.

We think we are not like our parents until we discover that we are.

Now, Darien and I do not a Unoko-Okonkwo relationship. Far from it, as I admire him tremendously, all the more so because he has taken a path far different from mine: I am a professor who found a position he loved and stayed there for 36 years whereas Darien is an entrepreneurial soul who will work for a company for only as long as he is learning new things. When the learning ends, he goes off in search of new opportunities. He only recently left a company where he was paid very well in order to start his own company. Yet for all his different interests, Darien admires my dedication to my students and my love of literature

As we talked, I found myself thinking back to frustrating telephone conversations with my own father, who was a professor of French literature. He too would not call me—I would always be the one to initiate the discourse—and he was always working conversations around to his own concerns. Furthermore, since I admired him tremendously, I could never figure out why our conversations never got as deep as I wanted them to get. Instead, I found myself listening to him discussing his course syllabi, just as Darien hears me talking about my book, my blog, and my tennis game. While I also express enthusiasm for his own endeavors (as my father did with mine), I’m not able to add much if anything to Darien’s understanding of them. He has ventured into waters that are unfamiliar to me.

In short, while I thought I had a different relationship with Darien than I had with my father, I find myself replicating the same patterns. Like Okonkwo.

Unlike Okonkwo, however, I have read Things Fall Apart and can learn from these frustrations. While I don’t know much about the world of business, I can (if I listen carefully) apply works of literature where appropriate. Darien is an avid reader—he read Moby Dick while commuting and, like his father, is a big Tom Jones fan—so if we discover useful parallels, we can both learn something. And have fun at the same time, with each bringing something to the table.

Anyway, I made a special point of calling him on Father’s Day. And we had (I think) a substantive conversation.