Note: If you wish to receive, via e-mail, (1) my weekly newsletter or (2) daily copies of these posts, write to me at rrbates1951@gmail.com. Comments may also be sent to this address. I promise not to share your e-mail with anyone. To unsubscribe, write here as well.

Thursday

My postcolonial Anglophone literature courage at the University of Ljubljana got off to a good start yesterday as I taught an excerpt from Edward Said’s Orientalism and then applied it to excerpts from H. Rider Haggard’s She and Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness. Tomorrow I’ll report on our discussion of Rudyard Kipling’s “The Man Who Would Be King” as we wrap up the section of the course on the colonialists’ perspective.

To kick off the discussion, I showed the class “The Snake Charmer,” the 1879 painting by France’s Jean-Léon Gérôme that graces the cover of Said’s book and that I used in yesterday’s post. Because I was fortunate to have a Turkish student in the class, I asked her if the painting was at all an accurate depiction of life in 19th century Turkey. Her vigorous dissent drove Said’s point home: the fantasies we impose on other cultures tell us far more about ourselves than they do about those other cultures.

While cultures have been imposing such fantasies on the Other since the dawn of time, Said notes that they become particularly dangerous when there is a power imbalance. Nineteenth and twentieth century politicians could confidently make generalizations about the people whose lives they impacted because “novelists, poets, translators, and gifted travelers” had been describing “the Orient” for years. In other words, they didn’t invent Orientalism to justify their policies but drew on common assumptions about Middle Eastern people and cultures.

So what were some of these assumptions? Said writes that, in British minds, “the Oriental” was irrational, depraved, childlike, and “different” while “the European” was rational, virtuous, mature, and “normal.”

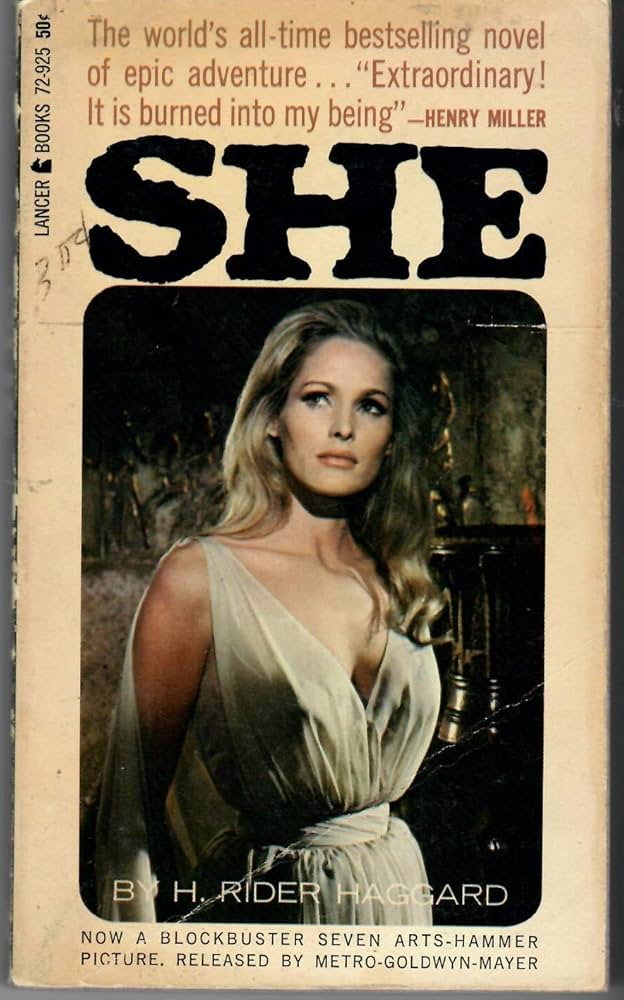

Our discussion of Said set up nicely our incursion into She, Haggard’s 1886 adventure novel where two British explorers, following an ancient map, make their way into deepest, darkest Africa and discover a beautiful but evil queen who has found the secret to eternal life and youth. The novel traffics in various racist tropes: while Ayesha rules over dark-skinned cannibals, she herself is white since who but white people could have built the engineering marvels in which she resides?

The excerpt we read allowed us to see Orientalizing, exoticizing and brutalizing at work. The dark savages make it clear that the country needs British civilization whereas the beautiful queen adds an emotional dimension to conquest: Brits prove their manhood by conquering the feminized landscape. One of the students noted British colonists venturing to the Americas in the 1600s were also fed this drama, seeing the New World almost as a virgin (Virginia) to be mastered. “Oh my America, my new found land,” rhapsodizes John Donne as he watches his lover strip down in his poem “To His Mistress Going to Bed.”

If our Orientalizing tells us more about ourselves than the colonized, what do we learn about 19th century Brits. Well, being sexually repressed, their sexual imaginations ran rampant when they learned about Middle Eastern polygamy and harems, even though—in real life—those were as tightly regulated as social regulations always are. Here’s Haggard’s own rampant imagining in a scene where She does a virtual striptease for the narrator:

Then all of a sudden the long, corpse-like wrappings fell from her to the ground, and my eyes travelled up her form, now only robed in a garb of clinging white that did but serve to show its perfect and imperial shape, instinct with a life that was more than life, and with a certain serpent-like grace that was more than human. On her little feet were sandals, fastened with studs of gold. Then came ankles more perfect than ever sculptor dreamed of. About the waist her white kirtle was fastened by a double-headed snake of solid gold, above which her gracious form swelled up in lines as pure as they were lovely, till the kirtle ended on the snowy argent of her breast, whereon her arms were folded. I gazed above them at her face, and—I do not exaggerate—shrank back blinded and amazed. I have heard of the beauty of celestial beings, now I saw it; only this beauty, with all its awful loveliness and purity, was evil—at least, at the time, it struck me as evil. How am I to describe it? I cannot—simply I cannot!

One of the students pointed out that Haggard is engaged in the kind of cataloguing of body parts that earlier poets practiced, most notably Andrew Marvell in “To His Coy Mistress.”

Although Haggard is fairly lightweight while Joseph Conrad is major talent, there are some surprising similarities. Conrad too talks about barbarous savages and beautiful women at the heart of “the dark continent.” First, barbarism. Conrad’s narrator imagines Romans, newly arrived after Julius Caesar’s conquest, gazing about in horrified fascination:

Imagine him here—the very end of the world, a sea the color of lead, a sky the color of smoke, a kind of ship about as rigid as a concertina—and going up this river with stores, or orders, or what you like. Sand-banks, marshes, forests, savages,—precious little to eat fit for a civilized man, nothing but Thames water to drink. No Falernian wine here, no going ashore. Here and there a military camp lost in a wilderness, like a needle in a bundle of hay—cold, fog, tempests, disease, exile, and death—death skulking in the air, in the water, in the bush. They must have been dying like flies here….He has to live in the midst of the incomprehensible, which is also detestable. And it has a fascination, too, that goes to work upon him. The fascination of the abomination—you know, imagine the growing regrets, the longing to escape, the powerless disgust, the surrender, the hate.

And then there’s an alluring female, although Conrad’s “wild and gorgeous apparition of a woman” has the same skin color as her subjects. So I guess that’s some progress:

She walked with measured steps, draped in striped and fringed cloths, treading the earth proudly, with a slight jingle and flash of barbarous ornaments. She carried her head high; her hair was done in the shape of a helmet; she had brass leggings to the knee, brass wire gauntlets to the elbow, a crimson spot on her tawny cheek, innumerable necklaces of glass beads on her neck; bizarre things, charms, gifts of witch-men, that hung about her, glittered and trembled at every step. She must have had the value of several elephant tusks upon her. She was savage and superb, wild-eyed and magnificent; there was something ominous and stately in her deliberate progress. And in the hush that had fallen suddenly upon the whole sorrowful land, the immense wilderness, the colossal body of the fecund and mysterious life seemed to look at her, pensive, as though it had been looking at the image of its own tenebrous and passionate soul.

Notice how Marlow sees her as a personification of “the immense wilderness” itself. She represents “mysterious and fecund life” whereas the “dark continent” possesses a “tenebrous and passionate soul.” For this woman, ivory hunter Kurtz has abandoned his angelic and ethereal fiancé, along with his mission to civilize and convert the heathen.

Back again to how Orientalizing, exoticizing, and barbarizing the Other is a self-reveal. The Victorians had tied their manhood to conquest, which is easy to do if your empire is expanding. The explorers in She are manly men—lion-like Leo Vince is compared to a god—and while Ayesha may dominate others, she falls all over herself to please him. At the same time, back at the home front, the suffragette movement was on the rise and many women were no longer willing to play “the angel in the home” (Kurtz’s fiancé excepted, which is why Marlow admires her so much). Furthermore, doubts were beginning to set in about empire-building itself, especially with the excesses of King Leopold in the Belgian Congo and with the expansionist Boer War in South Africa.

To be sure, Haggard’s novel has no problem with colonialism and doesn’t even mention its monetary benefits. But Conrad saw up close the greed and barbarism of the colonists, which seriously undermined the façade of bringing civilization and Christianity to Africa—just as, in Francis Ford Coppola’s remake of the novel, the on-the-ground reality of the Vietnam War brought into question America’s expressed intention to spread democracy. So where Haggard can treat British colonialism as a boyish lark, Conrad is plunged into existential despair.

There’s a problem, of course, with using another culture as mere backdrop for your anguished self-doubt. In a famous essay that we’ll be reading next week, Nigerian novelist Chinua Achebe takes Conrad to task for treating Africans as props in an internal drama. But Conrad is at least grappling with substantive issues. As I write in my book, “if you want to understand the crisis of capitalism, Heart of Darkness is a good book to study. Just don’t read it to understand Africa.”

The bottom line here is that literature of various sorts can be used both to support and to question colonialist projects—and also, as we will see next week with Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart, to push back against them. It’s why courses like this, putting students in touch with literature from different cultures around the globe, are so important.

On a personal note: It so turns out that I am one degree of separation from Cecil Rhodes, the great imperialist who dreamed of a continent-long British railway stretching “from Capetown to Cairo” and for whom Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe and Zambia) was named. So my own family history is tied up with the colonialist enterprise.

Here’s the story: My great grandfather, Edwin Fulcher, was an accountant for a South African diamond mine when Rhodes was there. Family lore has it that at one time they were the only two Englishmen in the small town where they resided.

This would have been in the 1890s when Rhodes was using his political power to expropriate land from Black Africans. He was also using his monopoly power to take over British-owned mines so I’m thinking it might have been more of a chance encounter, with my great grandfather seeing what Rhodes was up to. He was not a fan. My grandmother, who in some ways was a sweet and very Victorian woman–somewhat like Kurtz’s fiancé, come to think of it–would have been a little girl.

Eventually Fulcher’s accounting partner would run off with their funds, forcing the family to relocate. They ended up in Evanston, Illinois, where my grandmother met and married Alfred Bates.