Monday

My friend Rebecca Adams has alerted me to an article, “Opportunity Knocks for Liberal Education,” by political science professor Matthew Moen. A liberal arts education, the author argues, will save us from authoritarianism because it specializes in the two things that counteract it: truth and citizenship formation.

While Moen’s heart is in the right place, I have my doubts about his idealism. About truth and citizenship, here’s what he has to say:

The search for truth is right now the only antidote to the poison of disinformation in America. The creation of virtuous citizens is central to building a new, more inclusive democracy.

Because truth addresses what “ails our nation” and citizenship is “what is required to fix it,” a liberal arts education, he contends, is perfect. The job of liberal arts advocates, therefore, is to be very clear in their messaging: “we just have to effectively convey that to the public.”

There’s an implied criticism of how academe is going about this at the moment.

It will take faculty members and administrators speaking effectively and repeatedly to the public about liberal education — which doesn’t fit easily into anyone’s job description on campus. It will require deliberate outreach to a broad swath of Americans who have come to believe that colleges and universities are primarily places of political indoctrination. Our message needs to be that colleges and universities have always been and will always remain — no matter what else they may do — institutions where students and faculty search for truth in classrooms and labs, in courses as divergent as biology, philosophy and politics.

Instead of getting involved in intricate conversations, the academy, he says, should just be pounding one message over and over:

Hey, America, liberal education teaches students to discern truth and be good citizens, and those are needed to help heal our nation.

I’ve written numerous times about how literature does both. In one column, for instance, I quoted Indian novelist Salman Rushdie describing literature as, essentially, a “no bullshit zone.” The classics, he says, are especially critical these days (he’s writing during the Trump administration) given constant political lying:

[W]hen we read a book we like, or even love, we find ourselves in agreement with its portrait of human life. Yes, we say, this is how we are, this is what we do to one another, this is true. That, perhaps, is where literature can help most. We can make people agree, in this time of radical disagreement, on the truths of the great constant, which is human nature.

At different times on this blog, I’ve noted that figures like Aristotle, Sir Philip Sidney, Samuel Johnson, Percy Shelley, Frederic Engels, and W.E.B. Du Bois have all held up literature’s truth-telling at its most important aspect, with the last three willing to embrace even authors they politically disagreed with if they told the truth about the human condition.

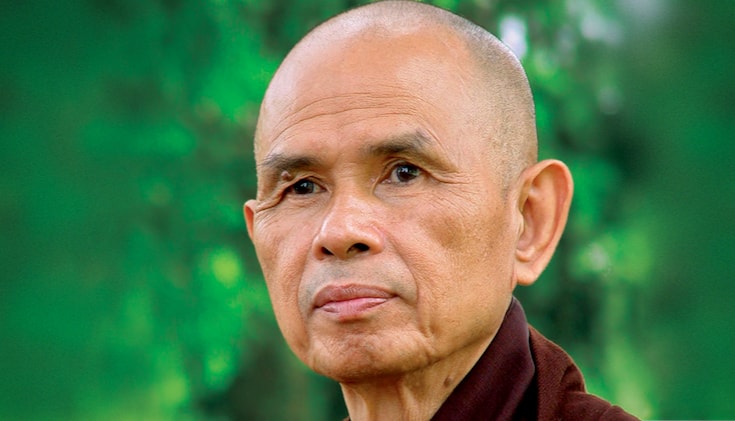

As for citizenship, I’ve also written several posts about how literature can help forward that end, especially a post on philosopher Nussbaum, who sees a literary education as essential in the formation of responsible voters.

But while I wholeheartedly embrace Moen’s ideals, I question how well this political scientist has really sized up the opposition. Everything he sees as wrong with America he attributes to some vague malaise as opposed to a deliberate neo-fascist strategy. He talks about “a new, more inclusive democracy” as something we should all want (and indeed we should) whereas it’s this very inclusiveness that is under attack. He wants liberal arts discussions that are free of politics whereas rightwing authoritarians see the liberal arts themselves as the problem. In other words, the right has already politicized the liberal arts, characterizing what colleges do as unchristian, anti-white, and socialist.

That’s because, to use Moen’s verb, they see the liberal arts university “indoctrinating” its students when it teaches them to respect difference (including gender, sexual race, ethnic, and class difference); to trust the scientific method; to engage in reasoned discourse; and to follow the truth wherever it takes them. A clear statement of the university’s truth-telling and citizen-forming goals, rather than bringing such people around, will only convince them that the university is the enemy. After all, we’ve seen climate scientists, immunologists, and others being drawn, against their will, into political battles. They’ve found themselves attacked by people who hate the very Enlightenment principles upon which their fields rest.

In short, better messaging is not going to do the trick.

Moen also wants academe to promote “civic/civil education.” While I like the idea, prepare for fierce resistance. If good citizens, as he believes, will engage in reasoned discourse about “voter suppression and intimidation, voter registration, mail-in ballots, election security, judicial intervention, redistricting, gerrymandering, and the Electoral College,” then those who don’t want reasoned discourse on these matters are not going to want good citizens. They’ll do everything in their power to either undermine such education or corrupt it.

So while I agree that we should proclaim the values that Moen embraces, I want us to act as well. We’re going to have to engage in politics, whether it’s over school library collections; history, English, biology and social science curricula; enlightened public policy; or a host of other areas. The liberal arts will either enter the fray or get buried.