Note: If you wish to receive, via e-mail, (1) my weekly newsletter or (2) daily copies of these posts, write to me at rrbates1951@gmail.com. I’ll subscribe you via Mailchimp for the weekly or email you directly for the daily (your choice). Comments may also be sent to this address. I promise not to share your e-mail with anyone.

Tuesday

“In times like these, it will not be the politicians or the priests that save us, it will be the poets and the painters,” writes John Pavlovitz in a recent Substack essay that is well worth reading.

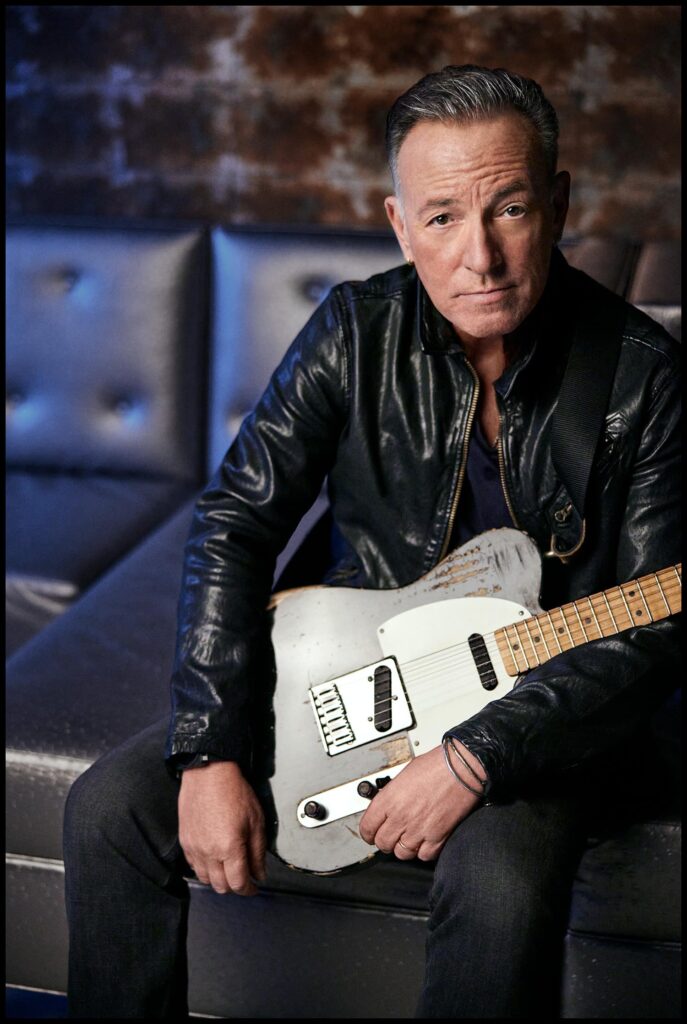

In this particular essay, he’s speaking about Bruce Springsteen, who lit into Donald Trump during his recent tour. I’ll get to Springsteen in a moment. But let’s look first at Pavlovitz’s essay, which notes how the Trump administration is more or less systematically attacking the arts:

There’s a reason Trump and his Administration are trying to financially cripple PBS and NPR, why they have infiltrated the Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts, why they’ve declared war on our libraries and museums, why they’re slashing funding for art, music, and theatre programs to young people:

Fascists are terrified of artists.

“Creativity,” Pavlovitz goes on to say

has always been one of the most powerful weapons against authoritarianism, against injustice, against dehumanization. Art is wild and unruly. It defies political proclamation, it does not respect authority, and it refuses subjugation.

Once released into the world, it cannot be contained or legislated away.

For evidence, Pavlovitz points to the various rights movements, which took off in the 1960s and 1970s, resulting in humanitarian advances that Trumpism is currently trying to reverse:

From the sustaining songs of Black people kidnapped and forced to build the scaffolding of this nation hundreds of years ago, to the clarion calls for justice in the ‘60s folk movement, to the Black Arts Movement, to the Chicano Mural Movement, to the LGBTQ+ Arts movements in the face of the AIDS crisis, to the Hip Hop movements, to Black Lives Matter, to this present Resistance movement—the hands and voices and bodies of artists have confronted injustice, awakened the souls of humanity, and fortified the fighters.

I’ve written about such artists—those who give voice to the previously voiceless—dozens if not hundreds of times in this blog over the past 16 years. While the artists do not necessarily talk about politics, their works by their very existence are political. If this was not clear before Trump launched into his assault on diversity, equity and inclusion, it’s clear now.

And because of Trump’s wholesale attacks on difference, all of today’s artists need to push back. As Pavlovitz asserts, “We need the plays and the songs and the murals and prophetic words that help us imagine a place better than this one. We need beauty and melody and drama and dissonance.”

Springsteen is doing his part, sometimes directly, sometimes through his art. His recent tour included the following indictment:

In my home, the America I love, the America I’ve written about, that has been a beacon of hope and liberty for 250 years, is currently in the hands of a corrupt, incompetent and treasonous administration.

And later in the session:

In America, the richest men are taking satisfaction in abandoning the world’s poorest children to sickness and death. This is happening now.

In my country, they’re taking sadistic pleasure in the pain they inflict on loyal American workers.

They’re rolling back historic civil rights legislation that has led to a more just and plural society.

They are abandoning our great allies and siding with dictators against those struggling for their freedom. They are defunding American universities that won’t bow down to their ideological demands.

They are removing residents off American streets and, without due process of law, are deporting them to foreign detention centers and prisons. This is all happening now.

A majority of our elected representatives have failed to protect the American people from the abuses of an unfit president and a rogue government. They have no concern or idea for what it means to be deeply American.

The America l’ve sung to you about for 50 years is real and regardless of its faults is a great country with a great people. So we’ll survive this moment. Now, I have hope, because I believe in the truth of what the great American writer James Baldwin said. He said, “In this world, there isn’t as much humanity as one would like, but there’s enough.” Let’s pray.

While endorsing such comments, Pavlovitz is more interested in Springsteen as a poet singer than as polemicist. “Land of Hope and Dreams,” he says, “paints a word picture of the journey to a place where equity and justice, and liberty are reached, where our destinies are tethered together”:

This train carries saints and sinners

This train carries losers and winners

This train carries whores and gamblers

This train carries lost souls

I said, this train, dreams will not be thwarted

This train, faith will be rewarded

This train, hear the steel wheels singin’

This train, bells of freedom ringin’

Another Substack blogger, the incomparable Greg Olear, has chosen another Springsteen song to make a similar point. “Badlands” may have been written in 1978 but it applies equally well today. (Olear includes a link to the song in his essay). About the opening stanza, Olear writes, “If there is a better metaphor for our collective emotional state, four months into the Trump Redux, I have yet to encounter it”:

Light’s out tonight

Trouble in the heartland

Got a head-on collision

Smashin’ in my guts, man

Caught in a crossfire

That I don’t understand

The next stanza, Olear says, brings to mind the worn-out oppositional tactics of the Democratic leadership:

But there’s one thing I know for sure, girl

I don’t give a damn

For the same old played out scenes

I don’t give a damn for just the in-betweens

Honey, I want the heart, I want the soul

I want control right now

And then the terror that many are currently feeling:

To talk about a dream, try to make it real

You wake up in the night

With a fear so real

You spend your life waiting

For a moment that just don’t come

Well don’t waste your time waiting

Springsteen follows up this description of our condition with a call to action. And while action may result in a broken heart of disappointment, we must undertake it nevertheless:

Badlands, you gotta live it everyday

Let the broken hearts stand

As the price you’ve gotta pay

Keep pushin’ ’til it’s understood

These badlands start treating us good

Those at the bottom of the social scale are the ones who are most straight on the facts:

Workin’ in the field

You get your back burned

Workin’ ‘neath the wheels

You get your facts learned

Baby, I got my facts

Learned real good right now

You better get it straight, darlin’

And what are these facts that we need to get straight? An insatiable hunger to possess and control is a driving force. Springsteen makes a subtle point here since the speaker’s longing for control can get out of hand. In America’s rags to riches story, too often the newly enriched seek to oppress those whose status they once shared:

Poor man wanna be rich

Rich man wanna be king

And a king ain’t satisfied

‘Til he rules everything

I wanna go out tonight

I wanna find out what I got

What then follows, Olear says, is “the exact energy I’ve tried all these years to summon with my ‘We shall prevail!’ sign-off. This—this right here—is the Apostles’ Creed of the capital-R Resistance”:

Well, I believe in the love that you gave me

I believe in the faith that could save me

I believe in the hope

And I pray that some day

It may raise me above these badlands.

And then, following a repeat of the refrain—”Let the broken hearts stand/ As the price you’ve gotta pay”—comes the finale. Olear says the song culminates in “a moment of pure, visceral defiance”:

For the ones who had a notion

A notion deep inside

That it ain’t no sin to be glad you’re alive

I wanna find one face

That ain’t looking through me

I wanna find one place

I wanna spit in the face of these badlands.

Pavlovitz notes that one of Springsteen’s earliest heroes was Woody Guthrie, whose inspiring depression-era songs helped usher in the great social welfare programs and income redistribution that have made our lives immeasurably better. Guthrie himself had to battle with “America First,” the MAGA of his day, and had etched on his guitar the words, THIS MACHINE KILLS FASCISTS.

As we face the biggest fascist threat since the 1930s, if not in our history, Pavlovitz all but prays,

May we stay connected to our muses, to our humanity, and one another.

May we in America arrive at that glorious place one day, and may the artists lead the way.

Amen.