Spiritual Sunday

Yesterday the Sewanee community filled our parish hall to remember my mother. It was an emotional occasion and I found myself in tears for much of it. I led off with the following remarks, concluding with a Stevenson poem.

Welcome to this community celebration of Phoebe Robins Strehlow Bates—or “mama,” as her children called her. I am Robin Bates, the oldest of her four sons. I was three when Phoebe and Scott moved to Sewanee in 1954, so Jonathan, David, and Sam and I all grew up here, attending Sewanee Public School, as it was known at the time, and then the Sewanee Military Academy (later Sewanee Academy).

Many of you know about Phoebe’s intense dedication to making the Sewanee community work. How she helped start the Sewanee Chorale and the Sewanee Crafts Fair, how she and my father participated in the suit that integrated Franklin County Schools, how she founded the Sewanee Siren—now the Sewanee Mountain Messenger—and ran it for 18 years, laboriously typing it up on stencils every Wednesday night.

What you may not know is that she spent much of her life with back pain, having been in a car accident as a teenager and, even before that, having been told by a doctor that she would have back problems all her life. I was in awe at how she refused to let the pain get in her way and how she seldom complained. In addition to multiple back surgeries, she partly held the pain at bay by a vigorous swimming regimen—she’d been a champion swimmer in high school—and would sometimes swim a mile a day.

Since many of you know her chiefly through her “Bard to Verse” column in the Messenger, I thought I’d focus my remarks on her love of literature. She started the tradition of a weekly poem in the Siren, each issue of which started out with a poem, and she co-edited Bard to Verse in the Messenger for years until my father died, at which point she edited it herself up until two weeks before her death. She was also a voracious novel reader and especially loved 19th century novels, especially those of Jane Austen and Anthony Trollope. We once figured out that she’d read 17 of Trollope’s 51 novels.

I think what she loved about Trollope and Austen was their focus on community—about how, if you live a principled life, the community thrives, while if you don’t, things fall apart. She loved the extensive network of family and community relationships that is to be found in those novels. And while she was sweet and civil to everyone, she could be critical of people who were just out for themselves. She shared Austen’s and Trollope’s satiric eye for those who sacrificed others for their own convenience, and she also shared their wit. As she saw it, Sewanee was filled with colorful characters who could have stepped out of Austen’s Pride and Prejudice or Trollope’s Can Your Forgive Her.

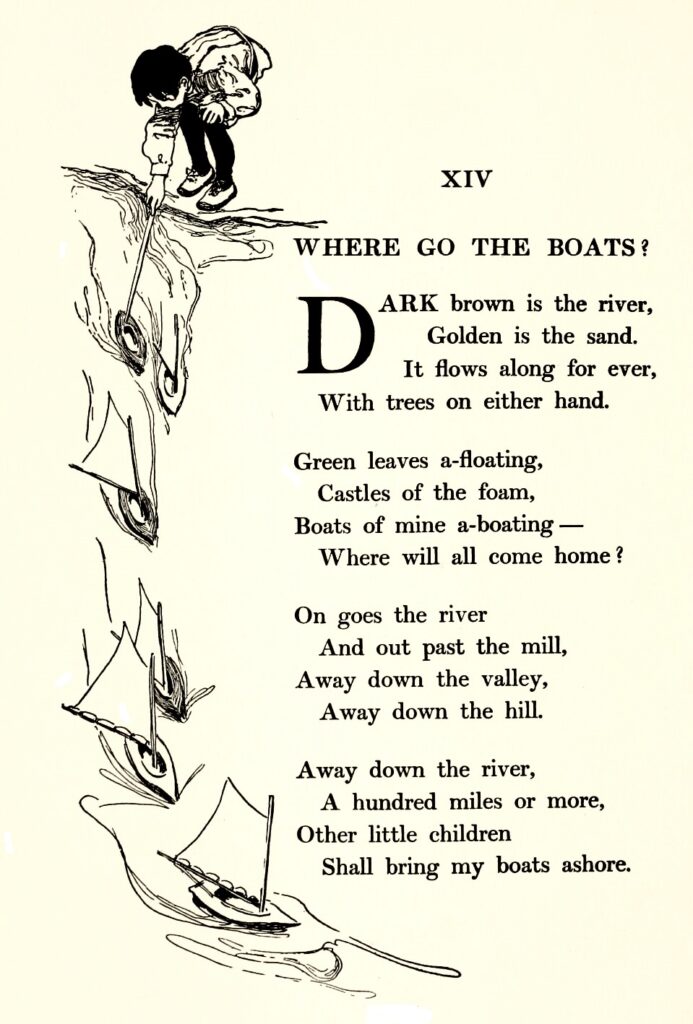

Returning to poetry, Mama used to say that she thought that people underestimated Robert Louis Stevenson’s poetry, especially the Child’s Garden of Verses. I’ve therefore chosen a poem from that collection. Although it’s about a child launching toy boats, I think it also sums up the way that what you do in life has ripple effects that continue on long after your death. I like to think this is my mother’s legacy:

Where Go the Boats?

By Robert Louis Stevenson

Dark brown is the river,

Golden is the sand.

It flows along for ever,

With trees on either hand.

Green leaves a-floating,

Castles of the foam,

Boats of mine a-boating –

Where will all come home?

On goes the river

And out past the mill,

Away down the valley,

Away down the hill.

Away down the river,

A hundred miles or more,

Other little children

Shall bring my boats ashore.

Bon voyage, mama.