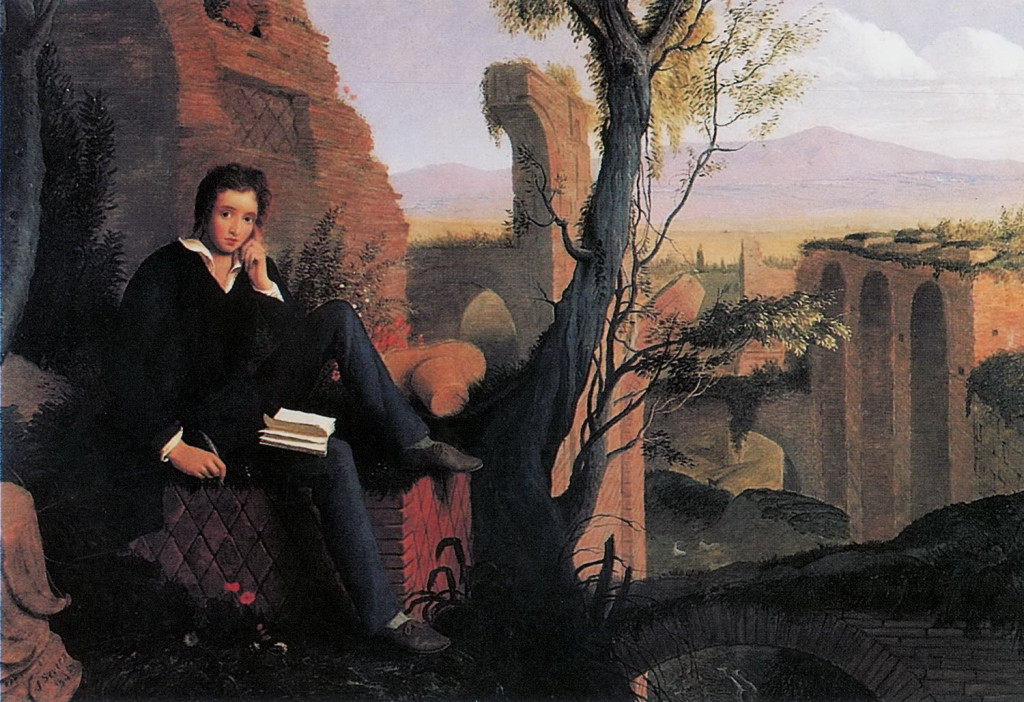

It’s often said that everything of importance has already been said, perhaps by Plato and Aristotle. As I look back at what thinkers of the past have written about literature’s power to change lives, I’m finding that there is some truth this. Rereading Shelley’s Defence of Poetry, for instance, I’ve discovered that ideas I thought were my own I actually borrowed from his famous 1821 essay 35 years ago.

I’ll share these in a moment. But first, I want to qualify my opening statement. Even if nothing is new under the sun, ideas don’t exist in a vacuum. They must constantly be reframed for the world we live in now. This is true of literature as well, which must be reinterpreted by each new generation. Our needs change, as do the obstacles we must surmount, and texts and ideas that were once timely can go in and out of relevance depending on the circumstances.

In other words, it doesn’t matter that no idea is entirely new. What matters is that we are on a ceaseless quest to make sense of the world, and thinkers of the past help us find our place in it.

I had forgotten that Shelley’s essay directly takes on the project that is at the center of this blog. As he sees it, the great authors change the way we see the world. Ethics may give us rules to live by but poetry enlarges the moral imagination:

Poetry lifts the veil from the hidden beauty of the world, and makes familiar objects be as if they were not familiar; it reproduces all that it represents, and the impersonations clothed in its Elysian light stand thenceforward in the minds of those who have once contemplated them, as memorials of that gentle and exalted content which extends itself over all thoughts and actions with which it coexists. The great secret of morals is love; or a going out of our nature, and an identification of ourselves with the beautiful which exists in thought, action, or person, not our own. A man, to be greatly good, must imagine intensely and comprehensively; he must put himself in the place of another and of many others; the pains and pleasure of his species must become his own. The great instrument of moral good is the imagination; and poetry administers to the effect by acting upon the cause. Poetry enlarges the circumference of the imagination by replenishing it with thoughts of ever new delight, which have the power of attracting and assimilating to their own nature all other thoughts, and which form new intervals and interstices whose void forever craves fresh food. Poetry strengthens the faculty which is the organ of the moral nature of man, in the same manner as exercise strengthens a limb.

It’s hard to sum up all that Shelley is saying here, but I take away that poetry puts us in touch with what is noblest in humanity, even as it also shows us where we fall short. Love for humankind, imagining ourselves in the place of others, is what elevates us. Through reading literature we move beyond our narrow prejudices and are inspired to achieve our potential as a species. In his concluding paragraph Shelley writes,

The most unfailing herald, companion, and follower of the awakening of a great people to work a beneficial change in opinion or institution, is poetry.

And in his final lines:

It is impossible to read the compositions of the most celebrated writers of the present day without being startled with the electric life which burns within their words. They measure the circumference and sound the depths of human nature with a comprehensive and all-penetrating spirit, and they are themselves perhaps the most sincerely astonished at its manifestations; for it is less their spirit than the spirit of the age. Poets are the hierophants [interpreters of sacred mysteries] of an unapprehended inspiration; the mirrors of the gigantic shadows which futurity casts upon the present; the words which express what they understand not; the trumpets which sing to battle, and feel not what they inspire; the influence which is moved not, but moves. Poets are the unacknowledged legislators of the world.

Whew!

I know that my own project doesn’t sound quite so elevated. And yet, even in my small and everyday examples, I see literature enlarging us in the ways that Shelley talks about. Our daily chores and interactions, our workplace frustrations and our political disagreements, our joys and our tragedies take on a larger dimension when they are viewed through literature’s lens. Or rather, literature opens us up to see their deeper significance.

Shelley describes what this world would look like without literature. He is describing “the dark ages” here, which doesn’t do full justice to that time in history. Think of it rather as any society which can’t think beyond its own smallness:

Whatever of evil their agencies [ medieval institutions] may have contained sprang from the extinction of the poetical principle, connected with the progress of despotism and superstition. Men, from causes too intricate to be here discussed, had become insensible and selfish: their own will had become feeble, and yet they were its slaves, and thence the slaves of the will of others: lust, fear, avarice, cruelty, and fraud, characterized a race amongst whom no one was to be found capable of creating in form, language, or institution.

Shelley makes another point that particularly intrigues me—the poetic vision is bigger than the poet, who can be just as prejudiced and narrow as the rest of us. Just as I become smarter and more sensitive when I am reading literature—so do poets when they are composing it:

The person in whom this power resides, may often, as far as regards many portions of their nature, have little apparent correspondence with that spirit of good of which they are the ministers. But even whilst they deny and abjure, they are yet compelled to serve, that power which is seated on the throne of their own soul.

The best poets, Shelley says, are those that rise above their local prejudices and give themselves over entirely to artistic vision, which he compares to participation in a cause. Poets like Homer, Dante, and Shakespeare have entirely joined this cause whereas some others fall short:

A poet therefore would do ill to embody his own conceptions of right and wrong, which are usually those of his place and time, in his poetical creations, which participate in neither By this assumption of the inferior office of interpreting the effect in which perhaps after all he might acquit himself but imperfectly, he would resign a glory in a participation in the cause. There was little danger that Homer, or any of the eternal poets should have so far misunderstood themselves as to have abdicated this throne of their widest dominion. Those in whom the poetical faculty, though great, is less intense, as Euripides, Lucan, Tasso, Spenser, have frequently affected a moral aim, and the effect of their poetry is diminished in exact proportion to the degree in which they compel us to advert to this purpose.

In other words, we need to keep reading and writing with courage and integrity to stay in touch with our deep nobility. Otherwise, we become slaves to the wills of others and our own base appetites.