Wednesday

I continue to write about the Romantic imagination for my book (Better Living through Literature: A 2500-Year-Old Debate), exploring how the movement helped change the way we see nature. As we deal with the dire consequences of climate change—the recent U.N. report should scare the bejeezus out of all of us–I find it useful to review the role that literature can play in spurring us to action.

I’ve visited the issue regularly in this column but I look today at the origins of poetic warnings. The 18th century’s scientific and technological breakthroughs, which allowed allowed humans to control nature in unprecedented ways, also led to a separation. It’s easier to regard Nature as an object of Romantic reflection, after all, when it’s not starving, freezing, or otherwise killing you. Poets picked up on our growing separation from nature early, with William Blake talking of “dark Satanic mills” befouling England’s “green and pleasant land” and Wordsworth lamenting that we are out of tune with nature because “getting and spending we lay waste our powers.”

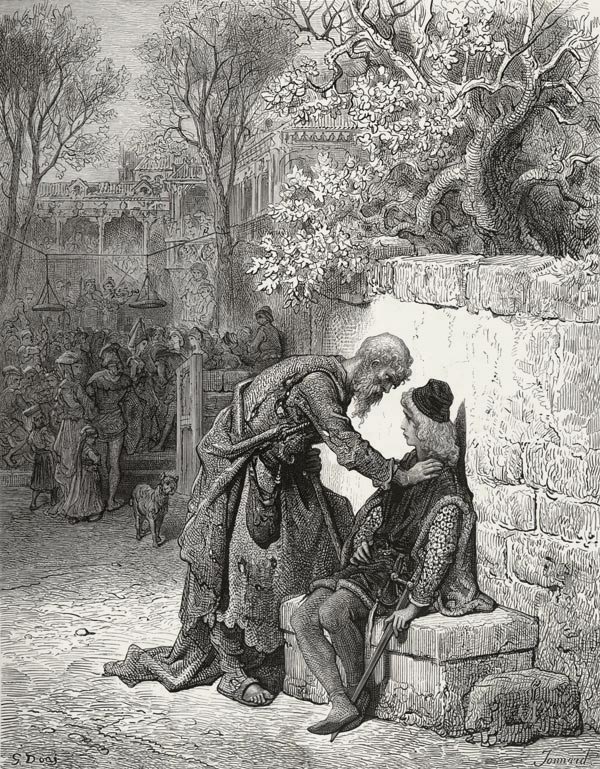

Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s Rime of the Ancient Mariner is particularly illuminating because it foregrounds the interaction between environmental poet and public. In the poem, an apparently mad prophet enters the scene and tells a compelling story about our alienation from nature. The story is so powerful that the young man he picks out as his audience “cannot choose but hear.”

Caught up in the excitement of exploring new lands that marked the age, the mariner sets out on a journey to the southern hemisphere. This apparent openness to new experience, however, is contradicted by an act of domination: the Mariner gratuitously kills a wandering albatross that the sailors have befriended. Having thereby announced his separation from the natural order, he experiences a spiritual sterility:

Water, water, everywhere,

And all the boards did shrink;

Water, water, everywhere,

Nor any drop to drink.

The very deep did rot: O Christ!

That ever this should be!

Yea, slimy things did crawl with legs

Upon the slimy sea.

Living a nightmarish death-in-life with his heart “as dry as dust,” the Mariner finds himself unable to pray. The albatross, meanwhile, has been hung around his neck, both as a punishment from his shipmates and a sign of the internal weight he is carrying. He is saved, however, by the sudden realization that he has a kinship with even the foulest of Nature’s creatures. In this transformation, the slimy things become marvelous creatures moving in shining tracks:

Within the shadow of the ship

I watched their rich attire:

Blue, glossy green, and velvet black,

They coiled and swam; and every track

Was a flash of golden fire.

O happy living things! no tongue

Their beauty might declare:

A spring of love gushed from my heart,

And I blessed them unaware:

Sure my kind saint took pity on me,

And I blessed them unaware.

The self-same moment I could pray;

And from my neck so free

The Albatross fell off, and sank

Like lead into the sea.

Having had this epiphany, he feels compelled to share his insight with others:

Since then, at an uncertain hour,

That agony returns:

And till my ghastly tale is told,

This heart within me burns.

I pass, like night, from land to land;

I have strange power of speech;

That moment that his face I see,

I know the man that must hear me:

To him my tale I teach.

In this particular instance, he has chosen a callow youth to hear what he has to say, a member of a wedding party who is intent on drinking and carousing. The mariner’s message has a Sunday school simplicity to it:

Farewell, farewell! but this I tell

To thee, thou Wedding-Guest!

He prayeth well, who loveth well

Both man and bird and beast.

He prayeth best, who loveth best

All things both great and small;

For the dear God who loveth us,

He made and loveth all.

Were he to deliver the message without the narrative or the poetry, however, it would fail to impress and we could not expect a change in behavior. It is the poetic imagination that draws the young man and holds him transfixed:

He holds him with his glittering eye—

The Wedding-Guest stood still,

And listens like a three years’ child:

The Mariner hath his will.

The Wedding-Guest sat on a stone:

He cannot choose but hear;

And thus spake on that ancient man,

The bright-eyed Mariner.

We also learn that the Mariner’s story has had an impact:

The Mariner, whose eye is bright,

Whose beard with age is hoar,

Is gone: and now the Wedding-Guest

Turned from the bridegroom’s door.

He went like one that hath been stunned,

And is of sense forlorn:

A sadder and a wiser man,

He rose the morrow morn.

In exploring humans’ relationship with nature, the Romantic poets increased our awareness of what it means to be human. In the rich tradition of nature literature that has followed, along with the exciting field of ecocriticism, our thinking has moved beyond daffodils and storms (Wordsworth, Byron) to what ecocritics call an “earth-centered approach.”

As a result, we no longer makes simple distinctions between the environment and culture, between “the natural” and the human, but examine how they are inextricably linked. If today we have an ever-growing list of authors using the full powers of the imagination to address the challenges of a rapidly changing environment—Wendell Berry, Barbara Kingsolver, and Margaret Atwood come immediately in mind—it’s because poems like Rime of the Ancient Mariner showed the way.

Literature alone won’t save us, of course. In the five-alarm fire we are confronting, we need all hands on deck, civic leaders, scientists, academics, activists, business leaders, military leaders, etc. The fate of our species hangs in the balance. But poets too have an important role to play, conveying the urgency in ways that other forms of rhetoric may not. May it lead all of us to rise sadder and wiser men and women.