Monday

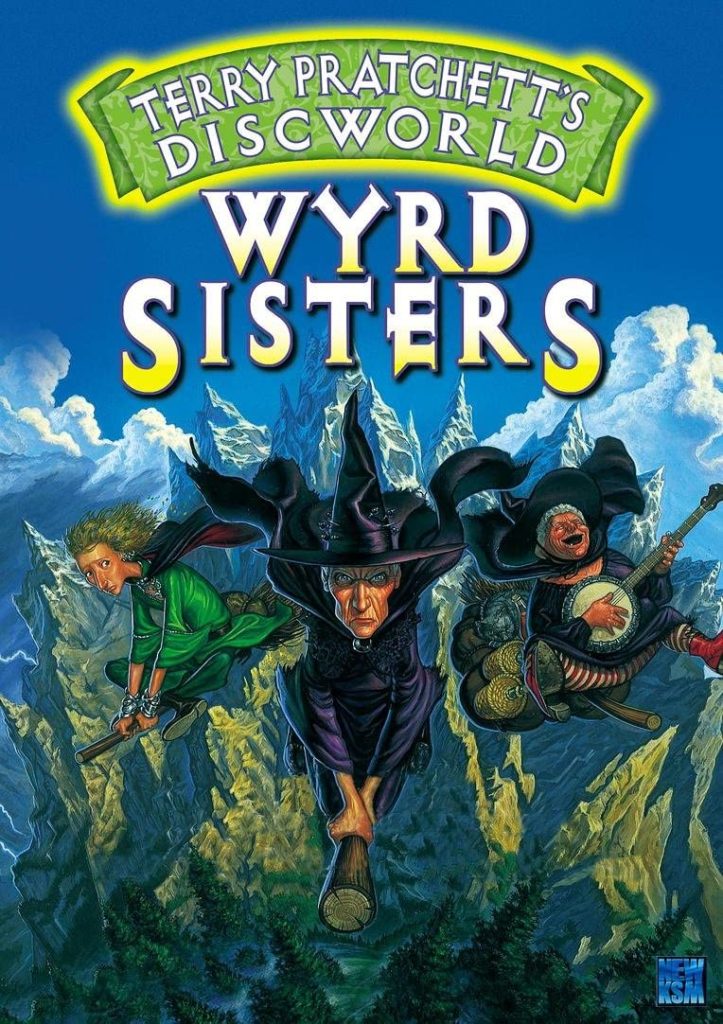

To stay sane during the pandemic, Julia and I have been working our way through Terry Pratchett’s Discworld series. Every few days we order the next batch from Sewanee’s library, picking them up from the front porch between 2-4. Pratchett’s unique blend of fantasy and comedy is a welcome relief from the madness.

Not that Pratchett avoid the world’s contentious issues. I’ve blogged on how well Pratchett uses the fantasy genre to grapple with bigotry and the challenges of living in a diverse society. He does as far better job on this score than either Tolkien or J.K. Rowling as humans, trolls, goblins, witches, vampires, dwarfs, leprechauns, and other creatures figure out how to coexist, even though they have radically different lifestyles and behaviors.

In Wyrd Sisters, the novel I’m reading at present, three Macbethian witches have saved the heir of King Verence, who has been assassinated by Duke Felmet. (The Shakespearean echoes are deliberate—it’s as though they’ve saved one of Macduff’s sons.) They then set cosmic wheels in motion so that he can be in a position to reclaim his throne. The usurping king’s relationship to the kingdom, meanwhile, reminds me of Donald Trump’s relationship to America.

Generally, Pratchett’s populace are fairly cynical about their kings, who have a long history of killing their predecessors to gain access to the throne. As witch Nanny Ogg explains, this is just politics as usual:

“Lots of people have killed each other to become king of Lancre. They’ve done all kinds of murder.”

“Don’t matter! Don’t matter!” said Granny, waving her arms. She started counting on her fingers. “For why,” she said. “One, kings go around killing each other because it’s all part of destiny and such and doesn’t count as murder, and two, they killed for the kingdom.”

Put in modern terms (and the terms Pratchett has in mind), although Tories and Labor or Democrats and Republicans battle for power—sometimes they even resort to dirty tricks—in the end they believe in the country. Obama, the Bushes, Clinton, Reagan, Carter, and even Nixon all were committed to the United States, even though they had different ideas of what was best for it. It’s different this time, however.

In Wyrd Sisters, the land itself rises up, sending signals to the nature-sensitive witches that something is amiss with Felmet. At one point, Granny Weatherwax opens her door and witnesses the following scene (the misspellings are deliberate):

Occupying the patch where the herbs grew in summer were the wolves, sitting or lolling with their tongues hanging out. A contingent of bears were crouched behind them, with a platoon of deer beside them. Occupying the metterforical stalls was a rabble of rabbits, weasels, vermine, badgers, foxes and miscellaneous creatures who, despite the fact that they live their entire lives in a bloody atmosphere of hunter and hunted, killing or being killed by claw, talon and tooth, are generally referred to as woodland folk.

They rested together on the snow, their normal culinary relationships entirely forgotten, trying to outstare her.

America’s own version of such a convergence is conservatives like William Kristol and George Conway making common cause with liberals like Nancy Pelosi and Rev. Al Sharpton.

The witches explore why the land is sending distress signals:

“I don’t reckon a lot of kingdoms do that sort of thing,” [Nanny Ogg] said. “You saw the theater. Kings and such are killing one another the whole time. Their kingdoms just make the best of it. How come this one takes offense all of a sudden?”

“It’s been here a long time,” said Granny.

“So’s everywhere,” said Nancy, and added, with the air of a lifetime student. “Everywhere’s been where it is ever since it was first put there. It’s called geography.”

“That’s just about land,” said Granny. “It’s not the same as a kingdom. A kingdom is made up of all sorts of things. Ideas. Loyalties. Memories. It all sort of exists together. And then all these things create some kind of life. Not a body kind of life, more like a living idea. Made up of everything that’s alive and what they’re thinking. And what the people before them thought.”

Incidentally, Robert Frost wrestles with a similar line of thought in “The Gift Outright,” the poem he recited at John F. Kennedy’s inauguration. “The land was ours before we were the land’s,” he writes. “She was our land more than a hundred years/Before we were her people.” At some point, however, we surrendered ourselves to the land and became, for better and for worse, inextricably entwined with it. America became “a living idea.”

Back to the witches:

“I can see you’ve been thinking about this a lot,” said Nanny, speaking very slowly and carefully. “And this kingdom wants a better king, is that it?”

“No! That is, yes. Look—” she leaned forward—”it doesn’t have the same kind of likes and dislikes as people, right?”

Nanny Ogg leaned back. “Well, it wouldn’t, would it,” she ventured.

“It doesn’t care if people are good or bad. I don’t think it could even tell, anymore than you could tell if an ant was a good ant. But it expects the king to care for it.”

Then she gets down to the difference in this case, which helps us understand how Trump differs from all previous presidents:

“[T]his new man just wants the power. He hates the kingdom.”

“It’s a bit like a dog, really,” said Magrat [the third witch]. Granny looked at her with her mouth open to frame some suitable retort, and then her face softened.

“Very much like,” she said. “A dog doesn’t care if its master’s good or bad, just so long as it likes the dog.”

“Well, then,” said Nanny. “No one and nothing likes Felmet. What are we going to do about it?”

This proves to be a difficult question because witches meddling in politics messes with nature’s laws. In this case, however, a foundational social contract is being violated, forcing the witches’ hand. On the other hand, the final result is totally unexpected.

The kingdom doesn’t get a perfect king, but we don’t need perfect kings. Applying Pratchett’s criteria of someone who cares about the kingdom, either Hillary Clinton or Jeb Bush would have been satisfactory presidents, and Joe Biden will certainly do. After all, the underlying commitment is there.