Acc. to the Southern Agrarians, slavery was peripheral to Southern history

Note: If you wish to receive, via e-mail, (1) my weekly newsletter or (2) daily copies of these posts, notify me at rrbates1951@gmail.com and indicate which you would like. I promise not to share your e-mail address with anyone. To unsubscribe, send me a follow-up email.

Wednesday

Recently I have been exploring my sudden fascination with William Faulkner, which has been furthered by Michael Gorra’s The Saddest Words: William Faulkner’s Civil War. Gorra compares Faulkner’s allusions to the war with what actually happened in order to figure out the accuracy and the honesty of the author’s vision of slavery and Jim Crow oppression. While occasionally Gorra catches the novelist sharing some of the South’s twisted versions of history, for the most part he says Faulkner gets things right.

He certainly is more accurate than the Southern Agrarians, a literary movement of poets and authors who celebrated the Lost Cause. I find Gorra’s reflections on the movement particularly interesting since I was personally acquainted with some of its leading figures, albeit only peripherally. Poet Alan Tate, one time editor of the Sewanee Review, became friends with my father after he retired to Sewanee, and Andrew Lytle, a later editor, was a prominent figure in Sewanee life. In fact, I was in a high school Latin class with Lytle’s daughter.

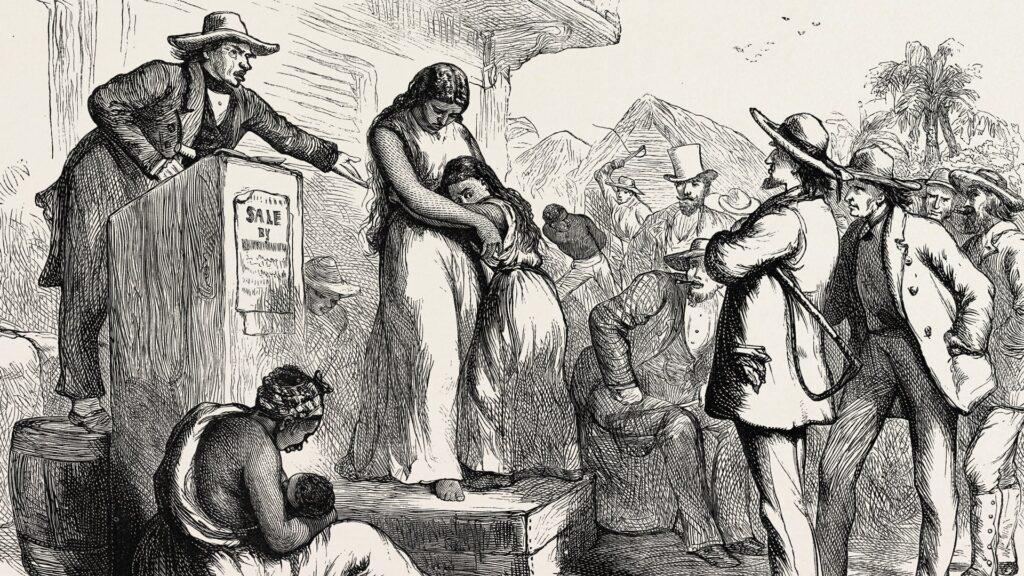

The Agrarians embraced the idea that the white rural South nobly resisted the encroachments of the North’s industrial capitalism. In doing so, Gorra says, the they downplayed or even ignored slavery, despite it having been the South’s primary economic engine:

[The Agrarians] made no apology for the Southern past or indeed for slavery itself, “a feature” that [poet John Crowe Ransom] described as “monstrous enough in theory, but, more often than not, humane in practice.” Instead, they pit a mythified Southern culture against what they saw as modernity’s dominant mode of life, defining an opposition between a pre-capitalist agricultural community on the one hand and a mechanical market-driven society on the other….They believed that the South [offered] the chance of a distinctive way of being, a separate line of historical development….Those who worked the soil remained identified with a particular spot of ground in a way that city folks could never be, and the Agrarians saw the subsistence farmer as the culture’s typical figure.

Gorra goes on to describe Lytle’s views after wryly observing that the novelist “spent far more of his own life in academia than he did on the farm.” Focusing on these farmers rather than on “the courtliness of plantation life,” Lytle portrayed them as having had “hardly anything to do with the capitalists and their merchandise.” In his idealized vision, they

work their own two hundred acres, churn their own butter, and make their own soap, and at midday they eat in such an unhurried fashion that an office worker would grow nervous. No “fancy tin-can salads…litter the table,” but there is always plenty of pot-likker.

Gorra notes that the Agrarians were influenced by Eliot and Yeats, who also dreamed of “a vanished wholeness, a lost organic world.” In other words, like Eliot (some of whose poetry the Sewanee Review published), they embraced poetic modernism to oppose modernity.

While Faulkner shared their enthusiasm for modernism (think how his narratives shift between different points of view and proceed often by doubling back on themselves), he had none of their sentimental nostalgia. Therefore, Gorra says Faulkner stayed away from the Agrarians, even though they admired him immensely:

[T]heir picture of the agricultural world is entirely without the extremity of his own: without the violence, or the sex, or the hatred, without the hunger and the bitter poverty; without the weather, and the laughter too. And their vision of the South lacks one thing more, one thing on which much though not all of the Yoknapatawpha cycle depends. Ransom writes that “abolition alone could not have effected any great revolution in society,” and the South that he and his fellows envision is in essence a South without black people. If abolition brought no change, then African-Americans are not an integral part of the culture; they can be simply written out, their presence suppressed in an appeal for tradition and stability.

In her book of essays Playing in the Dark, African American novelist Toni Morrison explains the effects of this suppression, noting how an “Africanist” presence is (I quote Gorra’s summation here)

deliberately pushed to the margins of American culture, a process that then allows that culture to be “positioned as white.” African Americans might be physically present but they carried no weight in the world that Ransom and his colleagues imagined: their very existence stood as an ideological blind spot, a fact of Southern life that the Agrarians worked hard to ignore.

If Morrison admires Faulkner as much as she does, it may be in part because he understands the fragility of White identity. As I’ve noted in recent posts, Faulkner shows how thin the line between White and Black is and how Whites often turned to acts of horrendous violence to bolster the distinction. Put another way, Whites used violence to back up their insistence on the separation of the races because they feared the separation was not as absolute as they claimed.

The Agrarian urge to minimize slavery helps explain how Sewanee Public School taught me Tennessee History in seventh grade. My teacher Fred Langford barely mentioned it and insisted that the war was caused by economic factors (as though slaves didn’t figure into the economy!). Although I have grappled with racism a lot since then, and even taught courses in Black literature, Faulkner is teaching me that there are even deeper levels of repression and denial than I realized.

Why should this be of interest to anyone other than a septuagenarian returning to his hometown in the South to retire? Well, the country as a whole still hasn’t faced up to its racial history, and currently there are reactionary forces everywhere that are trying to keep it that way. This is what people mean when they say that Critical Race Theory—by which they mean the country’s racial history—shouldn’t be taught in schools. It’s not only southerners saying this.

One last thought: I recently watched the Netflix Dutch series Ares, which (spoiler alert) deals with the corruption that arises when a culture represses a shameful history. In the Netherlands’ case, this history is the 17th and 18th century slave trade, which is at the basis of the nation’s current prosperity. Repressing this history has led to a monstrous black sludge, which monied interests attempt to keep hidden (it is in their interests to avoid an accounting). To lead the organization, one must kill whatever is pure or precious in oneself.

Closing our eyes to our racist past generates its own black sludge. What racists kill in themselves is the acknowledgment that their fellows are human beings, not monsters. Faulkner understood this in a way that great artists understand our essential being, and in his novels he seeks to find a language for it and to show its impact.

His fiction—unlike the works of the Agrarians—will be relevant for a long time to come.