It has been horrifying to see the many instances of young unarmed black men being killed by vigilantes and police. Several times have we heard the police explain that the victims, including Michael Brown in Ferguson, were reaching for their guns. As MSNBC’s Joy Reid said the other night on All in with Chris Hayes, however, either this is a cover story that police use because they can always get away with it or there’s an epidemic of unarmed black men reaching for police firearms.

Sometimes the story takes novel twists—like the Louisiana black youth who “committed suicide” by shooting himself in the chest with a police revolver in a squad car while his hands were cuffed behind his back. Or the Walmart shopper who picked up a BB gun in a Walmart while talking on a cell phone and was gunned down.

This depressing news has me revisiting Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man since it’s one of the great books about how whites can’t see anything other than their own fears when they look at black men. The “stand your ground” laws have grown out of these fears, as have the juries’ decisions to find vigilante killers like George Zimmerman and Michael Dunn justified in killing innocent teenagers. After all, if the jurors can identify with the fears, then the killers are a step closer to reasonable doubt.

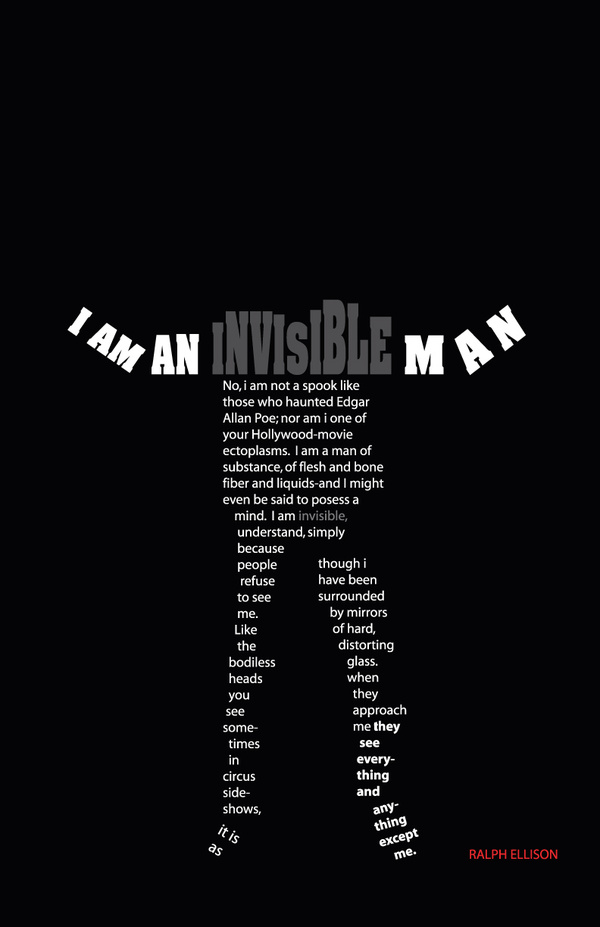

Here’s the famous opening of Invisible Man. Think of it as Projection 101:

I am an invisible man. No, I am not a spook like those who haunted Edgar Allan Poe; nor am I one of your Hollywood-movie ectoplasms. I am a man of substance, of flesh and bone, fiber and liquids — and I might even be said to possess a mind. I am invisible, understand, simply because people refuse to see me. Like the bodiless heads you see sometimes in circus sideshows, it is as though I have been surrounded by mirrors of hard, distorting glass. When they approach me they see only my surroundings, themselves, or figments of their imagination — indeed, everything and anything except me.

Nor is my invisibility exactly a matter of a bio-chemical accident to my epidermis. That invisibility to which I refer occurs because of a peculiar disposition of the eyes of those with whom I come in contact. A matter of the construction of their inner eyes, those eyes with which they look through their physical eyes upon reality. I am not complaining, nor am I protesting either. It is sometimes advantageous to be unseen, although it is most often rather wearing on the nerves. Then too, you’re constantly being bumped against by those of poor vision. Or again, you often doubt if you really exist.

You wonder whether you aren’t simply a phantom in other people’s minds. Say, a figure in a nightmare which the sleeper tries with all his strength to destroy.

Ellison then goes on to talk how frustrating it is to live as an invisible man. At one point he lashes out with violence to convince himself that he is real:

It’s when you feel like this that, out of resentment, you begin to bump people back. And, let me confess, you feel that way most of the time. You ache with the need to convince yourself that you do exist in the real world, that you’re a part of all the sound and anguish, and you strike out with your fists, you curse and you swear to make them recognize you. And, alas, it’s seldom successful.

He describes how he bumps into a white man and beats him up after he is called an insulting name. It’s worth noting such violent reactions have been the exception rather than the rule with most of the recent killings, even in Ferguson. True, there was some looting and some throwing of Molotov cocktails, but moderates worked to keep these to a minimum, even as the police seemed to go out of their way to provoke residents.

The Invisible Man says that his own violence is also the exception. I thought of President Obama’s muted response to Ferguson in the narrator’s description of his normal response:

Most of the time (although I do not choose as I once did to deny the violence of my days by ignoring it) I am not so overtly violent. I remember that I am invisible and walk softly so as not to awaken the sleeping ones. Sometimes it is best not to awaken them; there are few things in the world as dangerous as sleepwalkers.

I think Obama’s strategy has been to avoid stirring up racist whites. Instead, he tries to do things behind the scenes, sending his attorney general to investigate Ferguson and working towards incremental change.

Many of his black followers are frustrated, however. After all, he has many more options than the Invisible Man, who is in retreat at this point in the book, hibernating until he can find a basis upon which to act. Obama, by contrast, is supposedly the most powerful man on the planet. The president knows, however, that racism remains a powder keg that can still go off. He walks carefully.

In some ways, he is like President Bledsoe in the novel who knows his college will survive only if he doesn’t offend the white establishment too much. The narrator must be expelled from the school because he threatens to upset the delicate balance that the president is trying to maintain.

In our own time, rightwing commentators are doing everything they can to wake the sleepers up and get them to lash out at their nightmares. As a society, we still have a long way to go.

A note on the artist: Walter Logan’s design can be found at https://www.behance.net/gallery/3476483/The-Invisible-man-by-Ralph-Ellison