Monday

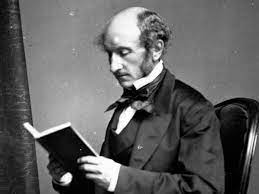

I’m currently looking into the work of John Stuart Mill, the great 19th century British philosopher who looked for ways to merge his utilitarian philosophy with the arts, especially literature. Utilitarians judge actions by the extent to which they bring about the greatest good to the most people. How literature enters into the discussion is not at first evident.

Except that, when he was a young man devoting himself to liberal causes, Mill hit a wall that plunged him into a deep depression. (I’ve written about that here.) While he could see that his cause was good—Mill advocated for broadening the British electorate, raising working wages, improving gender relations, and protecting free speech—something important seemed to be missing. That something missing was beauty, and Wordsworth came to the rescue. Mill tells us in his autobiography how the poet pulled him out of his depression:

What made Wordsworth’s poems a medicine for my state of mind, was that they expressed, not mere outward beauty, but states of feeling, and of thought colored by feeling, under the excitement of beauty. They seemed to be the very culture of the feelings, which I was in quest of. In them I seemed to draw from a source of inward joy, of sympathetic and imaginative pleasure, which could be shared in by all human beings; which had no connexion with struggle or imperfection, but would be made richer by every improvement in the physical or social condition of mankind. From them I seemed to learn what would be the perennial sources of happiness, when all the greater evils of life shall have been removed… I needed to be made to feel that there was real, permanent happiness in tranquil contemplation. Wordsworth taught me this…

Years later, when he had been named rector of Scotland’s University of St. Andrew’s, Mill talked about the importance of the arts, including poetry, to a well-rounded education. In today’s post I look at what he says in his inaugural address.

After singing the praises of math and the sciences, he turns to the arts. While he’s not quite ready to put them on the same level as those other disciplines, they are nevertheless essential:

There is a third division, which, if subordinate, and owing allegiance to the two others, is barely inferior to them, and not less needful to the completeness of the human being; I mean the aesthetic branch; the culture which comes through poetry and art, and may be described as the education of the feelings, and the cultivation of the beautiful.

Mill acknowledges that society accords the arts little respect. This has been especially the case with the so-called “fine arts” of painting and sculpture, which has been seen as

little more than branches of domestic ornamentation, a kind of elegant upholstery. The very words “Fine Arts” called up a notion of frivolity, of great pains expended on a rather trifling object—on something which differed from the cheaper and commoner arts of producing pretty things, mainly by being more difficult, and by giving fops an opportunity of pluming themselves on caring for it and on being able to talk about it.

The lack of respect extends even to poetry, Mill complains, despite its being “the queen of the arts.” Even though Shakespeare and Milton are praised, poetry is “hardly looked upon in any serious light, or as having much value except as an amusement or excitement…”

Among the culprits, Mill targets “commercial money-getting business,” which regards as “a loss of time” whatever does not contribute to profit. The businessman he characterizes as one

whose ambition is self-regarding; who has no higher purpose in life than to enrich or raise in the world himself and his family; who never dreams of making the good of his fellow-creatures or of his country an habitual object…

If we wish such people to practice virtue, Mill says, we must find a way to get them to experience virute as”an object in itself, and not a tax paid for leave to pursue other objects.” If we want them to develop an “elevated tone of mind” and see that there is more to life than mere self,” we can call on poetry, which instills in us lofty or heroic feelings while also “calming the soul.” Poetry, he says,

brings home to us all those aspects of life which take hold of our nature on its unselfish side, and lead us to identify our joy and grief with the good or ill of the system of which we form a part; and all those solemn or pensive feelings, which, without having any direct application to conduct, incline us to take life seriously, and predispose us to the reception of anything which comes before us in the shape of duty.

Mill then names names:

Who does not feel himself a better man after a course of Dante, or of Wordsworth, or, I will add, of Lucretius or the Georgics, or after brooding over Gray’s “Elegy [Written in a Country Churchyard]” or Shelley s “Hymn to Intellectual Beauty”?

After mentioning the other arts as equally worthy of respect, Mill returns to the topic of beauty in general, including the beauty of nature:

[T]he mere contemplation of beauty of a high order produces in no small degree this elevating effect on the character. The power of natural scenery addresses itself to the same region of human nature which corresponds to Art. There are few capable of feeling the sublimer order of natural beauty, such as your own Highlands and other mountain regions afford, who are not, at least temporarily, raised by it above the littlenesses of humanity, and made to feel the puerility of the petty objects which set men’s interests at variance, contrasted with the nobler pleasures which all might share.

Regardless of what profession we end up in, we must cultivate “these susceptibilities within us,” seeking out “opportunities of maintaining them in exercise.” If we have dull jobs, then it’s even more important to seek out art, which will show us how we are ennobled by “useful and honest work—which, “if ever so humble, is never mean but when it is meanly done…”

And there’s more. “He who has learnt what beauty is,” Mill says, “if he be of a virtuous character, will desire to realize it in his own life—will keep before himself a type of perfect beauty in human character, to light his attempts at self-culture.” To which end Mill cites Goethe, who believes that the Beautiful adds something essential to the Good:

Now, this sense of perfection, which would make us demand from every creation of man the very utmost that it ought to give, and render us intolerant of the smallest fault in ourselves or in anything we do, is one of the results of Art cultivation. No other human productions come so near to perfection as works of pure Art.

Beauty, Mill concludes,

trains us never to be completely satisfied with imperfection in what we ourselves do and are: to idealize, as much as possible, every work we do, and most of all, our own characters and lives.

In short, if you want to excel in your job and find meaning in your life, read literature.