Tuesday

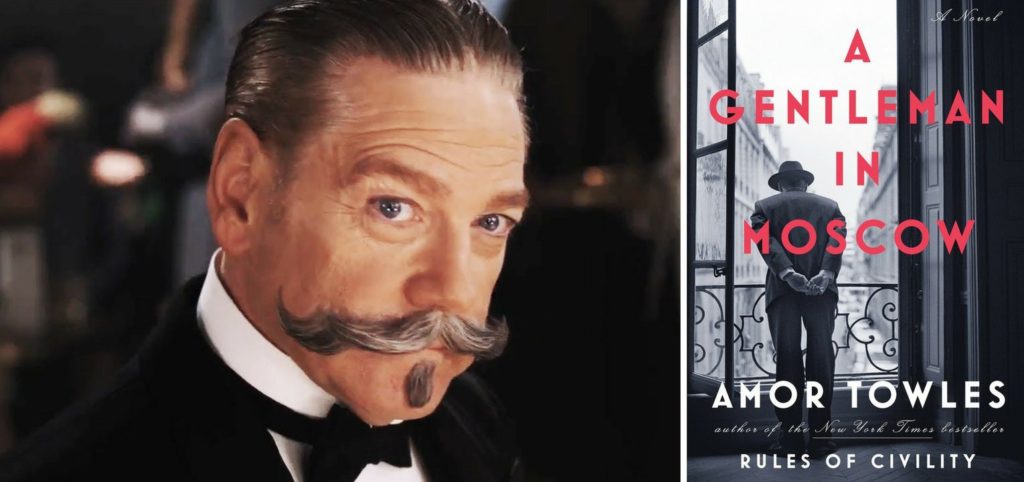

I’ve just begun reading Amor Towles’s A Gentleman in Moscow, which seems just the book for those confined to their apartments because of the coronavirus pandemic (or perhaps not). In 1922 Count Alexander Rostov is deemed to be an unrepentant aristocrat and condemned to settle in place in the grand Moscow hotel where he lives, although he must relocate from his sumptuous apartment to much smaller quarters in the attic. If he ever leaves the Metropol, the Bolsheviks say they will shoot him.

Like many in these days of Covid-19, Rostov turns to a much-delayed project, in his case reading Montaigne’s Essais. The work at first appears well chosen (for us as well as for Rostov) as Montaigne himself was confined to his tower while writing parts of it because of the plague.

At the point where I currently am, however, Rostov is finding the work a tough slog. I wonder how many of my students over the years have gone through some version of what he experiences:

It was somewhere in the middle of the third essay that the count found himself glancing at the clock for the fourth or fifth time. Or was it the sixth? While the exact number of glances could not be determined, the evidence did seem to suggest that the Count’s attention had been drawn to the clock more than once.

We thereupon get a detailed description of the clock:

Made to order for the Count’s father by the venerable firm of Breguet, the twice-tolling clock was a masterpiece in its own right. Its white enamel face had the circumference of a grapefruit and its lapis lazuli body sloped asymptotically from its top to its base, while its jeweled inner workings had been cut by craftsmen known the world over for an unwavering commitment to precision. And their reputation was certainly well founded. For as he progressed through the third essay (in which Plato, Aristotle, and Cicero had been crowded onto the couch with the Emperor Maximilian), the Count could hear every tick.

Ten twenty and fifty-six seconds, the clock said.

Ten twenty and fifty-seven.

Fifty-eight.

Fifty-nine.

Why, this clock accounted the seconds as flawlessly as Homer accounted his dactyls and Peter the sins of the sinner.

But where were we?

Ah, yes: Essay Three.

The Count shifted his chair a little leftward in order to put the clock out of view, then he searched for the passage he’d been reading. He was almost certain it was in the fifth paragraph on the fifteenth page. But as he delved back into the paragraph’s prose, the context seemed utterly unfamiliar; as did the paragraphs that immediately preceded it. In fact, he had to turn back three whole pages before he found a passage that he recalled well enough to resume his progress in good faith.

I’m predicting that Montaigne will grow on Rostov as they have kindred sensibilities. Both are humane, cosmopolitan, curious about the world, and interested in others. At the moment, however, it’s not getting better:

But as the Count advanced through Essays Eleven, Twelve, and Thirteen his goal seemed to recede into the distance. It was suddenly as if the book were not a dining room table at all, but a sort of Sahara. And having emptied his canteen, the Count would soon be crawling across sentences with the peak of each hard-won page revealing but another page beyond….

Well then, so be it. Onward crawled the Count.

At another point in those early days, Rostov worrisomely finds himself counting the minutes between meals:

For several days…he had been fending off a state of restlessness On his regular descent to the lobby, he caught himself counting the steps. As he browsed the headlines in his favorite chair, he found he was lifting his hands to twirl the tips of moustaches that were no longer there. He found he was walking through the door of the piazza at 12:01 for lunch. And at 1:35, when he climbed the 110 steps to his room, he was already calculating the minutes until he could come back downstairs for a drink. If he continued along this course, it would not take long for the ceiling to edge downward, the walls to edge inward, and the floor to edge upward, until the entire hotel had been collapsed into the size of a biscuit tin.

Looking for models, Rostov thinks of others sentenced to a life of confinement, some fictional, some real:

For Edmond Dantes in the Chateau d’If [Dumas’s Count of Monte Cristo], it was thoughts of revenge that kept him clear minded. Unjustly imprisoned, he sustained himself by plotting the systematic undoing of his personal agents of villainy. For Cervantes, enslaved by pirates in Algiers, it was the promise of pages as yet unwritten that spurred him on. While for Napoleon on Elba, strolling among chickens, fending off flies, and sidestepping puddles of mud, it was visions of a triumphal return to Paris that galvanized his will to persevere.

Rostov ultimately settles on Daniel Defoe’s most famous creation:

But the count hadn’t the temperament for revenge; he hadn’t the imagination for epics; and he certainly hadn’t the fanciful ego to dream of empires restored. No. His model for mastering his circumstances would be a different sort of captive altogether: an Anglican washed ashore. Like Robinson Crusoe stranded on the Isle of Despair, the Count would maintain his resolve by committing to the business of practicalities. Having dispensed with dreams of quick discovery, the world’s Crusoes seek shelter and a source of fresh water; they teach themselves to make fire from flint; they study their island’s topography, its climate, its flora and fauna, all the while keeping their eyes trained for sails on the horizon and footprints in the sand.

Rostov thereupon counts up his assets, especially the many gold coins he has squirreled away in the legs of his desk, and figures out how to convert them into useful items.

Like Betteredge in Wilkie Collins’s Moonstone, Rostov has discovered better living through Robinson Crusoe.