Friday

Reposted with modifications from September 10, 2016

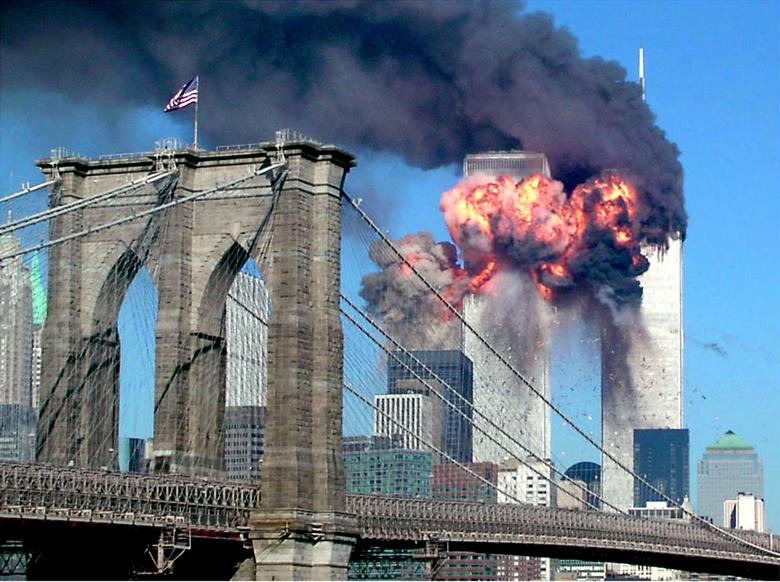

On September 11, 2001 and for six days afterwards, Lucille Clifton wrote poems exploring the attack. In other words, for a week she used poetry as a daily meditation to process what had happened.

At the time, Lucille was a colleague of mine at St. Mary’s College of Maryland, and we have posted all of them on plaques around St. John’s Pond, which sits in the middle of our campus. As one walks around the pond, one can read the sequence in its entirety.

The first poem turns on its head what it means to believe that God has blessed America. Often Americans assert that we are blessed because, as a wealthy and safe country, we are “exempt” from the suffering experienced “in otherwheres/israel ireland palestine.” Clifton notes that, with the attacks, we received a different kind of blessing, one that is in line with Jesus reaching out to the wretched of the earth: God has blessed us with the knowledge of what these “otherwheres” regularly experience:

1 Tuesday 9/11/01

thunder and lightning and our world

is another place no day

will ever be the same no blood

untouchedthey know this storm in otherwheres

israel ireland palestine

but God has blessed America

we singand God has blessed America

to learn that no one is exempt

the world is one all fear

is one all life all death

all one

In Wednesday’s poem, Clifton reminds us that Muslims no less than Christians are God’s children. God has multiple names and many tongues. This is not the time to focus on divisiveness, she says, either anger against Muslims or anger against those targeting Muslims. This is a time to pray together under one flag, “warmed by the single love/ of the many tongued God.”

2 Wednesday 9/12/01

this is not the time

i think

to note the terrorist

inside

who threw the brick

into the mosque

this is not the time

to note

the ones who cursed

Gods other name

the ones who threatened

they would fill the streets

with arab children’s blood

and this is not the time

i think

to ask who is allowed to be

american America

all of us gathered under one flag

praying together safely

warmed by the single love

of the many tongued God

Thursday’s poem uses a passage from Genesis (28:12) to honor the firemen who gave their lives. There we read that, while dreaming, Jacob “saw a stairway resting on the earth, with its top reaching to heaven, and the angels of God were ascending and descending on it.”

3 Thursday 9/13/01

the firemen

ascend

like jacob’s ladder

into the mouth of

history

Friday’s poem refers to the historical suffering of oppressed groups and passes along to all Americans an insight Clifton has struggled to learn as an African American woman: victims are not to blame for their suffering. While various rightwing preachers like Jerry Falwell said that the 9/11 attacks were in retribution for America’s toleration of homosexuality, Clifton reassures Americans that we have done nothing “to deserve such villainy.”

4 Friday 9/14/01

some of us know

we have never felt safeall of us americans

weepingas some of us have wept

beforeis it treason to remember

what have we done

to deserve such villainynothing we reassure ourselves

nothing

Saturday’s poem invokes Jesus and asks whether there is a higher purpose at work in our suffering. Lucille wonders whether there will be miracles of love in store for us, even as she acknowledges that the intention of “the gods” is difficult to understand:

5 Saturday 9/15/01

i know a man who perished for his faith.

others called him infidel, chased him down

and beat him like a dog. after he died

the world was filled with miracles.

people forgot he was a jew and loved him.

who can know what is intended? who can understand

the gods?

Sunday’s poem is dedicated to Lucille’s new granddaughter, born five days before the attacks. As she looks over the St. Mary’s River that flows by our campus, Lucille is struck by the calm, which is in marked contrast with the attacks. While she is well aware of humanity’s history of injustice and the many reasons to hate—she is “cursed with long memory”—she chooses to love instead.

Her granddaughter, she notes, is born innocent into a violent world. While Bailey will become aware of the bad, however, she will also become cognizant of the good. Buoyed by new life, Lucille talks about how she loves all of the world, despite “the hatred and fear and tragedy.” Ultimately, love trumps all.

6 Sunday Morning 9/16/01

for baileythe st. marys river flows

as if nothing has happenedi watch it with my coffee

afraid and sad as are we allso many ones to hate and i

cursed with long memorycursed with the desire to understand

have never been good at hatingnow this new granddaughter

born into a violent worldas if nothing has happened

and i am consumed with love

for all of itthe everydayness of bravery

of hate of fear of tragedyof death and birth and hope

true as this riverand especially with love

bailey fredrica clifton goinfor you

It so happened that Rosh Hashanah fell upon September 17 in 2001, prodding Lucille to find symbolic significance in the Jewish new year and the supposed anniversary of Adam and Eve. While human evil emerged from the Garden of Eden, so did human love. Lucille writes that “what is not lost” from that original connection with God “is paradise.” In the sweet and delicious image of “apples and honey,” we see that Lucille believes that not all has been lost:

7 Monday Sundown 9/17/01

Rosh Hashanah

i bear witness to no thing

more human than hatei bear witness to no thing

more human than loveapples and honey

apples and honeywhat is not lost

is paradise

And so we continue on, finding something to salvage in even the grimmest of times.