Note: If you wish to receive, via e-mail, (1) my weekly newsletter or (2) daily copies of these posts, notify me at rrbates1951 at gmail dot com and I will send it/them to you. I promise not to share your e-mail address with anyone. To unsubscribe, send me a follow-up email.

Wednesday

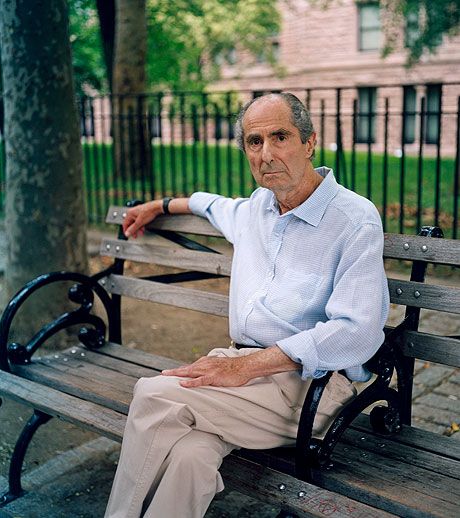

When my sons and their children were visiting us over Christmas, I had a moment of revelation that I connected with a small moment that occurs in Philip Roth’s The Human Stain. It’s not related to any of the novel’s main themes, but that’s the thing about literature: sometimes it provides tiny but useful windows for individual readers.

Before sharing it, however, allow me a detour about how the novel applies to a recent event that occurred at Hamline University. As Jill Filipovic reports the story,

In a course on global art history, adjunct professor Erika López Prater showed an image of a 14th-century painting that depicted the prophet Muhammad. On the class syllabus, she noted that the course would include images of religious figures, including Buddha and Muhammad, and that students could reach out if they had concerns—none did. Before showing the image, she told students that she was going to show it, and gave them the option to opt out—none did.

And yet for showing the image, she was essentially let go.

The Hamline administration, responsible for maintaining a diverse community, has since tied itself into explanatory knots, with respect for minority students seeming to clash with intellectual freedom and freedom of speech. In my mind, the professor handled the situation well while the administration botched the response, but liberalism has always had a tough time in such situations. Authoritarian conservatives may think they have more moral clarity, but Governor Ron DeSantis’s attempts to censor academics in Florida’s state universities reveal their true colors: such people just ignore or ride roughshod over the sensibilities of people who don’t think like them.

Anyway, there’s a college kerfuffle in Human Stain as well. Coleman Silk, a former revered dean and now professor, refers to a couple of African American students as “spooks” when they start missing his classes. “Spooks” was once a derogatory term applied to African Americans—I don’t know if racists still use it—but it’s unclear that the teacher knows this. And it’s not like Silk has used the n-word. It appears that the situation will be resolved until, unexpectedly, he angrily resigns.

At first glance, the spooks incident seems to be Roth indulging in a not very interesting caricature of academe, a case of political correctness run amok featuring overly sensitive students and cowed colleagues and administrators. Roth being Roth, however, there are layers upon layers to the story, the major one being that Silk himself is a Black man who has successfully passed as White for his entire professional life. Issues of motivation arise, including the question of whether he applied a racist term to Black students because of his own self-contempt. And what does it mean that Silk has also passed himself off as Jewish? Suddenly the narrative has morphed from a story about oversensitivity to a profound exploration of American identity.

What could Hamline learn from Human Stain? Well, college is an opportunity to engage in a similarly complex exploration of values and traditions, and that’s what the administration could have done. For instance, it could have set up a forum exploring, among other things, why many (although not all) Muslims object to portraits of Mohammed. Perfunctorily firing a teacher just looks like the college was siding with the most trenchant strains of Islam.

But all this is taking me away from my original thought, so back to that. When my sons showed up for Christmas, I was astounded at how they walked in, confident and self-assured in how they were taking on the world’s challenges. I watched in awe as Darien negotiated million-dollar contracts for a company he has just started and the same as English professor Toby articulated teaching insights and book ideas (and all this while managing his four children). Gazing at these two men, I was put in mind of Silk’s sons when they show up for his funeral.

Narrator Nathan Zuckerman reports that the Silk sons succeed beyond his wildest expectations:

The service for Coleman had been arranged by his children…The idea to bury him out of Rishanger, the college chapel, was a family decision, the key component of what I realized was a well-planned coup, an attempt to undo their father’s self-imposed banishment and to integrate him, in death if not in life, back into the community where he had made his distinguished career.

The funeral service includes one of Coleman’s colleagues, the college’s first Black professor, coming to Silk’s defense—“The alleged misconduct never took place. Never.”—and apologizing for not having stood up for him. Zukerman realizes that the turnout and the apology have also been engineered by Silk’s extremely competent sons:

That the place was nearly full was probably no chance occurrence. They must have been on the phone ever since the crash, mourners being rounded up the way voters used to be herded to the polls when the old Mayor Daley was running Chicago. And how they must have worked over Keble, whom Coleman had especially despised, to induce him voluntarily to proffer himself as the scapegoat for Athena’s sins. The more I thought about these Silk boys twisting Keble’s arm, intimidating him, shouting at him, denouncing him, perhaps even outright threatening him because of the way he had betrayed their father two years back, the more I liked them—and the more I liked Coleman for having sired two big, firm, smart fellows who were not reluctant to do what had to be done to turn his reputation right side out.

And further on:

It was hard to believe, given the ardor and the resolve, that out in California they were college science professors. You would have thought they ran Twentieth Century Fox.

Okay, so I can’t imagine Darien and Toby twisting arms to this extent. But yes, they are two big, firm, smart fellows.

Further thought on Hamline: Whether coerced or not, parts of Professor Keble’s funeral oration remind us of the purpose of college. The liberal arts goal is to get students to think for themselves:

Here, in the New England most identified, historically, with the American individualist’s resistance to the coercions of a censorious community—Hawthorne, Melville, and Thoreau come to mind—an American individualist who did not think that the weightiest thing in life were the rules, an American individualist who refused to leave unexamined the orthodoxies of the customary and of the established truth, an American individualist who did not always live in compliance with majority standards of decorum and taste—an American individualist par excellence was once again so savagely traduced by death, robbed of his moral authority by their moral stupidity.

Then again, Coleman Silk’s belief that he could assert his individuality by denying his skin color—by which means he escaped rather than fought back against a censorious community—shows that these things are never easy. And fighting for the right to use the word “spooks” is not quite as heroic as Keble makes it sound.

Still, college should indeed be all about examining “the orthodoxies of the customary and of the established truth.” And these include Muslim orthodoxies, Christian orthodoxies, and liberal orthodoxies.