Thursday

I never would have anticipated that a host of literary issues would arise from a horrific conflict, but so it has been with Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Russia has one of the world’s great literary traditions—it rivals that of Great Britain’s—but it comes with a cost.

The cost is the suppression of other languages. Guilty of language chauvinism, Russia apparently has been ruthless in imposing its language on others. Some of the chauvinists, as a recent article in Literary Hub reveals, have been great authors.

“We must thank fate (and the author’s thirst for universal fame) for his not having turned to the Ukrainian dialect as a medium of expression, because then all would have been lost,” wrote Vladimir Nabokov in his 1959 study, Gogol. He continued: “When I want a good nightmare, I imagine Gogol penning in Little Russian dialect volume after volume….” What he calls the “Little Russian dialect” is none other than the Ukrainian language, which is about as close to Russian as Spanish is to Italian.

Author Askold Melnyczuk observes that Nabokov wasn’t alone but has been joined by countless Russian writers and intellectuals. This has me rethinking my recent interpretation of Joseph Brodsky’s poem “On Ukrainian Independence,” where the speaker describes the Ukrainian poet Shevchenko as a “bullshitter” when put up against the immortal Russian poet Alexander Pushkin. I argued for a distinction between the speaker and Brodsky, imagining that Brodsky was channeling the voice of a Russian chauvinist rather than expressing his own thoughts. While this might still be the case, I’m now wondering whether Brodsky himself doesn’t agree.

Ukraine certainly doesn’t regard Shevchenko as a bullshitter. Melnyczuk observes,

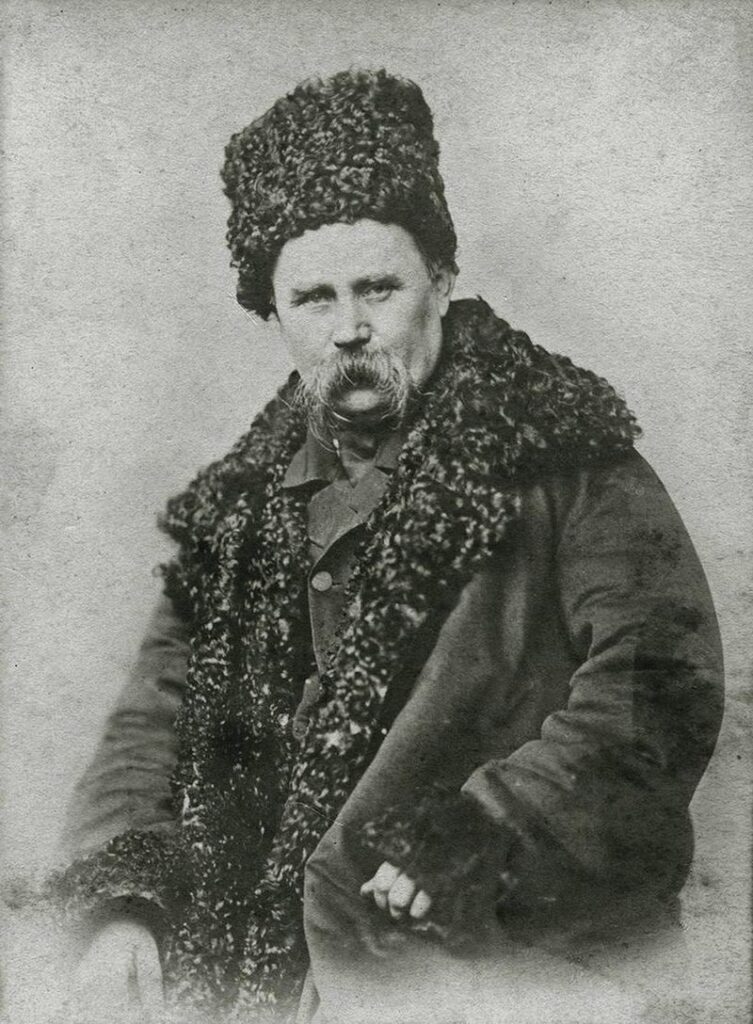

Ukraine is the only country I know of that was dreamed into existence by a poet. Born a serf in 1814, Taras Shevchenko was freed from slavery by the efforts of fellow artists. The painter-poet then took on himself the mission of telling the story of the indigenous people of Ukraine in their native tongue. For this the Russian empire punished him with decades of exile and imprisonment—this despite the fact that he wrote his prose in Russian. His Ukrainian-language poetry, however, had the effect of solidifying and fortifying the indigenous people’s sense of themselves. Ever since, poets have held a singular importance for the culture.

Actually, as I noted on Monday, Slovenia might be another such country. But set that aside. Melnyczuk says that, although Ukraine isn’t the only neighboring republic that has had Russian pushed down its throat, it has long been a particular target. First, two years after the abolition of serfdom in 1863, there was a ban on Ukrainian publications. Then, in 1876, Tsar Alexander

outlawed all publications in Ukrainian, including books imported from abroad. The policy also rendered illegal theater productions and performances of songs in Ukrainian. Russia feared that the indigenous peasant population might began to demand human rights and undermine Russia’s imperial claims.

Things then got particularly nasty in the 1930’s under Stalin in what Melnyczuk calls Ukraine’s “aborted Renaissance”:

In 1930 some 260 writers actively participated in the country’s literary life. By 1938 only 36 remained on the scene. Surveying the fates of the missing speaks volumes about the leitmotif of that decade: Of the 224 MIAs, 17 were shot; 8 committed suicide; 175 were arrested or interred; 16 disappeared without a trace. Only 7 died of natural causes. Belorussian culture was similarly decimated and thwarted by Stalin.

“The crime for which writers and intellectuals in former Soviet republics were punished,” Melnyczuk writes, “was that they dared aspire to autonomy and cultural independence.”

Russia is, of course, not the only country that has imposed its culture on others. France, England and others did so as well. Frantz Fanon, the legendary author of The Wretched of the Earth (1961), notes how the soft power of culture complements the hard power of state violence. Looking at how Europe colonized Africa, Fanon notes,

Every effort is made to bring the colonized person to admit the inferiority of his culture, which has been transformed into instinctive patterns of behavior, to recognize the unreality of his “nation.”

As a result, imported culture overwhelms native culture, which becomes “more and more shriveled up, inert, and empty.”

What Fanon says about national culture in general applies to literature. As African children are brought up reading, say, the French tragedies of Corneille and Racine, little is left of indigenous culture other than “a set of automatic habits, some traditions of dress, and a few broken-down institutions.” In these “remnants of culture,” Fanon says, “there is no real creativity and no overflowing life.” For instance, old folktales that grandparents tell their children, while they may survive, cannot address the issues of the day.

Fanon then goes on, however, to talk about a “literature of combat” in which a new sense of nation arises. Combative literature “calls on the whole people to fight for their existence as a nation,” Fanon says. As such, it “molds the national consciousness, giving it form and contours,” thereby opening up “new and boundless horizons.” Such literature Fanon characterizes as “the will to liberty expressed in terms of time and space.”

Such literature includes folk art, and Fanon notes that in Africa, the authorities, from 1955 on, began to systematically arrest storytellers. After all, the stories they told conflicted with the official colonialist narrative.

On Chris Hayes’s podcast Why Is This Happening?, Yale historian Tim Snyder, an expert on Russia and Ukraine as well as the author of the influential On Tyranny: Twenty Lessons from the Twentieth Century, recently spoke of Russia’s long history of cultural genocide. Russia, Snyder said, doesn’t acknowledge the existence either of the Ukrainian language or of Ukraine itself. To support his contention, he discussed a statement that appeared on Russia’s official state news agency site on April 3rd, just a few days after the discovery of the mass murders by Russian soldiers in Bucha.” Melnyczuk quotes Snyder in her article:

The Russian handbook is one of the most openly genocidal documents I have ever seen. It calls for the liquidation of the Ukrainian state, and for abolition of any organization that has any association with Ukraine. Such people, “the majority of the population,” …more than twenty million people, are to be killed or sent to work in “labor camps” to expurgate their guilt for not loving Russia. Survivors are to be subject to “re-education.” Children will be raised to be Russian. The name “Ukraine” will disappear.

But Ukraine can’t disappear if it has a vital literature, and Melnyczuk notes that “dozens of presses are rushing out translations of work by Ukrainian writers, whether they’re written in Ukrainian, Russian, Belarussian or Crimean Tatar.”

It’s ironic that the same language that has given us Pushkin, Tolstoy, Dostoevsky, Chekhov, Gogol, and Akhmatova should also be used to silence indigenous authors. And indeed, there has always been this push and pull in liberation movements: should Chinua Achebe write in Igbo or Salman Rushdie in Urdu, thereby limiting their readership—or should they write in the colonizers’ language, which expands their scope? By writing in English, Achebe was able to speak to much of Africa and Rushdie to all of India, but they gave up something in the process.

In his interview with Hayes, however, Snyder made an important point. Ukrainians have no difficulty moving between languages, which means that multiple literatures are available to them. Their multicultural nation is far more vibrant than monocultural Russia.

Which means that Gogol writing in Ukrainian might not have the nightmare that Nabokov feared.