Friday

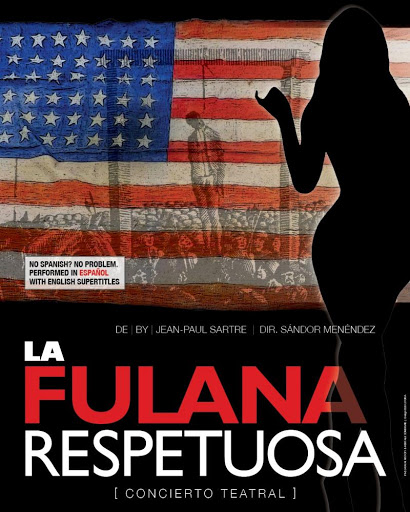

A hard-hitting essay about white privilege by Chicago Tribune columnist Dahleen Glanton brings to my mind Jean Paul Sartre’s play The Respectful Prostitute (1946). Sartre’s existential point is that we are always responsible for our actions, which is Glanton’s point as well.

After noting that “white people don’t like watching hardcore racism,” Glanton goes on to say,

But somehow, white people always find a way to get over it. You post your angst on social media to show which side you’re on.

Then before you know it, your drive-by rage is over.

You conclude that the terrible incident doesn’t affect you directly. So you drift back into oblivion, convinced there’s nothing you can do about racist cops or the racist society that breeds them.

In addition to posting on social media, Glanton could have mentioned the various groups piggybacking on Black Lives Matter to cause mayhem. When the disturbances end, they will go back to their white existences, leaving blacks to once again clean up the mess and suffer the consequences.

The column concludes,

Racists are counting on you to continue doing nothing. And you will not disappoint them.

Racists know some of you better than you know yourselves.

Inspired by the 1931 Scottsboro Incident, in which two prostitutes lied about being raped by nine black teenagers traveling through Alabama, Respectful Prostitute shows that whites always side with whites when push comes to shove, regardless of their professed principles.

In Respectful Prostitute, a black man has witnessed a white man shooting another African American, as has a white prostitute. To dispense with their testimony, the murderer’s brother (Fred Clarke) wants Lizzie to testify that the surviving black man has raped her. In that case, he will be lynched and the brother will escape prosecution.

Lizzie has principles, however, at least when it comes to causing the death of an innocent man. Clarke, who has slept with her the night before to set her up, starts pressuring her to change her story:

LIZZIE: What does that mean?

FRED: It means testifying against a white man in behalf of a nigger.

LIZZIE: But suppose the white man is guilty.

FRED: He isn’t guilty.

LIZZIE: Since he killed, he’s guilty.

FRED: Guilty of what?

LIZZIE: Of killing!

FRED: But it was a nigger he killed.

LIZZIE: So what?

FRED: If you were guilty every time you killed a nigger—

LIZZIE: He had no right.

FRED: What right?

LIZZIE: He had no right.

FRED: That right comes from up North. [A pause.] Guilty or not, you can’t punish a fellow of your own race.

LIZZIE: I don’t want to have anyone punished. They’ll just ask me what I saw, and I’ll tell them.

And further on:

FRED: What is there between you and this nigger? Why are you protecting him?

LIZZIE: I don’t even know him.

FRED: Then what’s the trouble?

LIZZIE: I just want to tell the truth.

FRED: The truth! A ten-dollar whore who wants to tell the truth! There is no truth; there’s only whites and blacks, that’s all.

As a prostitute, Lizzie is vulnerable to pressure, but she still manages to hold out against Fred. She’s less successful, however, against his senator father, who makes her feel sorry for the white killer, whose life will be upended by a murder charge. After softening her up by telling her about the murderer’s mother, he appeals to her patriotism:

THE SENATOR: Look: suppose Uncle Sam suddenly stood before you. What would he say?

LIZZIE [frightened]: I don’t suppose he would have much of anything to say to me.

THE SENATOR: Are you a Communist?

LIZZIE: Good Lord, no!

THE SENATOR: Then Uncle Sam would have many things to tell you. He would say: “Lizzie, you have reached a point where you must choose between two of my boys. One of them must go. What can you do in a case like this? Well, you keep the better man. Well, then, let us try to see which is the better one. Will you?”

LIZZIE [carried away]: Yes, I want to. Oh, I am sorry, I thought it was you saying all that.

THE SENATOR: I was speaking in his name. [He goes on, as before.] “Lizzie, this Negro whom you are protecting, what good is he? Somehow or other he was born, God knows where. I nourished and raised him, and how does he pay me back? What does he do for me? Nothing at all; he dawdles, he chisels, he sings, he buys pink and green suits. He is my son, and I love him as much as I do my other boys. But I ask you: does he live like a man? I would not even notice if he died.”

LIZZIE: My, how fine you talk.

THE SENATOR [in the same vein]: “The other one, this Thomas, has killed a Negro, and that’s very bad. But I need him. He is a hundred-per-cent American, comes from one of our oldest families, has studied at Harvard, is an officer—I need officers—he employs two thousand workers in his factory—two thousand unemployed if he happened to die. He’s a leader, a firm bulwark against the Communists, labor unions, and the Jews. His duty is to live, and yours is to preserve his life. That’s all. Now, choose.”

The African American man has a wife and kids as well, but he’s more of an abstraction whereas she can imagine the pain the white family will undergo. The same mental process helps explain why white juries often refuse to convict murdering cops. Nevertheless, after Lizzie signs the Senator’s statement, she feels that she’s “been had—but good!”

Her complicity isn’t at the end. Though he slept with her originally to entrap her, Fred finds that he needs her. He uses the full force of male and class entitlement to enforce his will, just as white entitlement has prevailed in the murder case. It’s enough to turn her.

In the final scene, Lizzie has just been hiding the black man—although another has been lynched for the shooting—and when Fred discovers him and tries to kill him, Lizzie is prepared to shoot Fred when he returns. He proves to be very persuasive:

FRED [approaching her slowly]: The first Clarke cleared a whole forest, just by himself; he killed seventeen Indians with his bare hands before dying in an ambush; his son practically built this town; he was friends with George Washington, and died at Yorktown, for American independence; my great-grandfather was chief of the Vigilantes in San Francisco, he saved the lives of twenty-two persons in the great fire; my grandfather came back to settle down here, he dug the Mississippi Canal, and was elected Governor. My father is a Senator. I shall be senator after him. I am the last one to carry the family name. We have made this country, and its history is ours. There have been Clarkes in Alaska, in the Philippines, in New Mexico. Can you dare to shoot all of America?

LIZZIE: You come closer, and I’ll let you have it.

FRED: Go ahead! Shoot! You see, you can’t. A girl like you can’t shoot a man like me. Who are you? What do you do in this world? Do you even know who your grandfather was? I have a right to live; there are things to be done, and I am expected to do them. Give me the revolver. [She gives him the revolver, he puts it in his pocket.] About the nigger, he was running too fast. I missed him [A pause. He puts his arm around her.] I’ll put you in a beautiful house, with a garden, on the hill across the river. You’ll walk in the garden, but I forbid you to go out; I am very jealous. I’ll come to see you after dark, three times a week—on Tuesday, Thursday, and for the weekend. You’ll have nigger servants, and more money than you ever dreamed of; but you will have to put up with all my whims, and I’ll have plenty! [She yields a bit to his embrace.] Is it true that I gave you a thrill? Answer me. Is it true?

LIZZIE [wearily]: Yes, it’s true.

FRED [patting her on the cheek]: Then everything is back to normal again. [A pause.] My name is Fred.

Normal for white America, as Glanton points out, is not having to think about police racism and white privilege. The police themselves are often Lizzies, used by those with money to clean up the messes left by egregious income inequality. In compensation, they are often given tacit permission to act out their power and racist fantasies within their limited domain.

Not that Sartre lets Lizzie, or anyone, off the hook, just as the cops must be held accountable for their brutality. We’re all responsible for our choices. As Sartre famously puts it, we are all condemned to be free.

His play, however, reveals that some are freer than others. It’s easier for privileged whites to exercise their freedom than for blacks and poor whites.

Respectful Prostitute has bearing on one other point that Glanton makes. Speaking of Alice Cooper, the Central Park stroller who claimed than a peaceful African American birdwatcher was attacking her after he called for her to leash her dog, Glanton notes that she’s not the real culprit:

Question why you allowed the Amy Cooper story to distract you from the issue of police brutality. Her lie about a black man attacking her in Central Park ws repulsive and she deserved to be rebuked, but it was only a blip in the larger arena of racism.

White women have been telling lies on black men since they were first brought to America in chains in 1619, and white women have been complicit. The most famous liar was Carolyn Bryant, who claimed Emmett Till whistled at her.

One of the main reason racism thrives is because white people too often miss the most important point. The biggest issues isn’t that a white woman lied. It’s the racist system that allowed Bryant’s husband his friends to drag Till out of bed, beat him to death and toss his body in the river—without repercussions.

It’s clear, in Respectful Prostitute, that the real villains are the white establishment, not the prostitute who lies under pressure.

Note also that what Lizzie gets from her surrender is another form of servitude. Her life will not be as hard as being black—with whiteness come certain privileges—but in her new life she’ll have to put up with Clarke’s whims (“and I’ll have plenty”).

Real freedom would come with Lizzy and the black man–the police and Black Lives Matter–joining forces against the Senator Clarkes of the world. What are the odds that will happen?