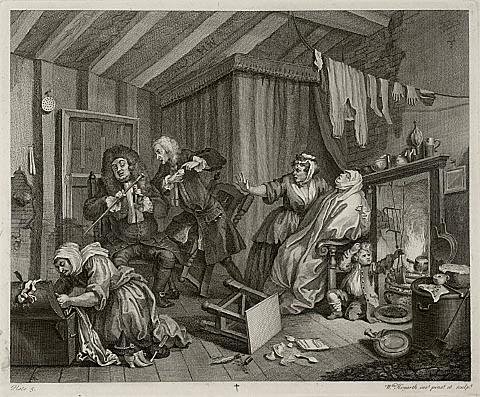

Doctors debate while patient dies in Hogarth’s “Harlot’s Progress,” plate V

Doctors debate while patient dies in Hogarth’s “Harlot’s Progress,” plate V

I’ve talked several times about my friend Alan, who has been battling cancer for a while now. At present he is still alive, still working out at the gym, and still in the dark about what kind of cancer he has. He longs for definite answers, and he has received a variety of diagnoses, predictions, and medical suggestions.

How is one to respond to such confusion? One resource is laughter, and some of the best comic depictions of doctors that I know appear in Henry Fielding’s Tom Jones. I’ll share a few passages in a moment.

But first to Alan. At one point he had a doctor saying that statisically it was unlikely that he would live beyond May of 2009. Now that he’s still alive, the cancer is being rediagnosed. Sometimes it seems to manifest itself as squamous cell, other times as adenocarcinoma, still other times as neuroendocrine cancer. Whatever it is, the cancer does have stem cell attributes, which make it very dangerous and easily spreadable. Then again, the tumors that once were growing in Alan’s lungs (and which have been removed surgically and by high intensity (‘Cyberknife’) radiation) have not (at least detectably) multiplied, as was once predicted.

One doctor has been impressed with my friend’s special nutritional diet. Another has been put off by it. One doctor has pushed hard for surgery, another for chemotherapy, a third originally recommended chemo but has expressed gratitude to Alan for getting him to rethink ways that cancer should be treated.

So Alan lives in perpetual uncertainty.

When I say that, however, a scene comes to me from Blade Runner, the film noir science fiction masterpiece by Riddley Scott. Harrison Ford has rescued a beautiful cyborg whose “termination date” (all the cyborgs have them) is unclear. “It’s too bad she won’t live!” shouts out a police official who is in the know, before adding, “But then again, who does?” Who does indeed? It’s not only cyborgs, after all, that have built-in termination dates.

As I share Fielding’s satire, I hope it doesn’t sound as though I’m taking cheap shots at doctors. In fact, all professions benefit from clever satirists, whose design is to keep them honest. (We English professors can benefit from satiric campus novels, often written by writers dissatisfied with their academic jobs.) As far as I can tell from watching Alan’s encounters with doctors, there are some who have weak patient skills, some who resent being questioned by patients, and some who don’t like to admit they might be wrong. On the other hand, he has also had doctors who have acknowledged his distress while admitting the uncertainties of medical science. Those doctors have joined him in a collaborative exploration of the great unknown that cancer still is, despite all that we’ve learned about it. They have learned as well as taught. These are the doctors we should all want.

After the jump are some doses of “the best medicine” from one of England’s comic geniuses:

Unwarranted pessimism

Towards the end of Tom Jones, the hero is told that a man who attacked him is at the point of death (following their duel), which means that he could be hanged. Later he learns the true story:

The surgeon, indeed, who first dressed him was a young fellow, and seemed desirous of representing his case to be as bad as possible, that he might have the more honor from curing him . . .

Dueling diagnoses

Two doctors are called to aid of the obnoxious Captain Blifil. As he has already died, there’s nothing they can do so they engage in a spirited debate about what killed him:

These two doctors, whom, to avoid any malicious applications, we shall distinguish by the names of Dr Y. and Dr Z., having felt his pulse; to wit, Dr Y. his right arm, and Dr Z. his left; both agreed that he was absolutely dead; but as to the distemper, or cause of his death, they differed; Dr Y. holding that he died of an apoplexy, and Dr Z. of an epilepsy.

Hence arose a dispute between the learned men, in which each delivered the reasons of their several opinions. These were of such equal force, that they served both to confirm either doctor in his own sentiments, and made not the least impression on his adversary.

To say the truth, every physician almost hath his favorite disease, to which he ascribes all the victories obtained over human nature. The gout, the rheumatism, the stone, the gravel, and the consumption, have all their several patrons in the faculty; and none more than the nervous fever, or the fever on the spirits. And here we may account for those disagreements in opinion, concerning the cause of a patient’s death, which sometimes occur, between the most learned of the college; and which have greatly surprized that part of the world who have been ignorant of the fact we have above asserted.

The reader may perhaps be surprized, that, instead of endeavouring to revive the patient, the learned gentlemen should fall immediately into a dispute on the occasion of his death; but in reality all such experiments had been made before their arrival: for the captain was put into a warm bed, had his veins scarified, his forehead chafed, and all sorts of strong drops applied to his lips and nostrils.

The physicians, therefore, finding themselves anticipated in everything they ordered, were at a loss how to apply that portion of time which it is usual and decent to remain for their fee, and were therefore necessitated to find some subject or other for discourse; and what could more naturally present itself than that before mentioned?

Underprescribing

The satire in this instance is less applicable to modern times, where often doctors overprescribe rather than underprescribe (thereby running up medical costs). But it’s witty enough to include here:

There is nothing more unjust than the vulgar opinion, by which physicians are misrepresented, as friends to death. On the contrary, I believe, if the number of those who recover by physic could be opposed to that of the martyrs to it, the former would rather exceed the latter. Nay, some are so cautious on this head, that, to avoid a possibility of killing the patient, they abstain from all methods of curing, and prescribe nothing but what can neither do good nor harm. I have heard some of these, with great gravity, deliver it as a maxim, “That Nature should be left to do her own work, while the physician stands by as it were to clap her on the back, and encourage her when she doth well.”

Bad bedside manners

The physician who attends to Tom for a broken arm (sustained while saving Sophia from a horse accident) appears more interested in demonstrating his knowledge than in making the patient feel comfortable:

The surgeon now ordered his patient to be stript to his shirt, and then entirely baring the arm, he began to stretch and examine it, in such a manner that the tortures he put him to caused Jones to make several wry faces; which the surgeon observing, greatly wondered at, crying, “What is the matter, sir? I am sure it is impossible I should hurt you.” And then holding forth the broken arm, he began a long and very learned lecture of anatomy, in which simple and double fractures were most accurately considered; and the several ways in which Jones might have broken his arm were discussed, with proper annotations showing how many of these would have been better, and how many worse than the present case.

Having at length finished his labored harangue, with which the audience, though it had greatly raised their attention and admiration, were not much edified, as they really understood not a single syllable of all he had said, he proceeded to business, which he was more expeditious in finishing, than he had been in beginning.

Patient advocates

Tom’s problem in the above scene here is that he has no patient advocate—unlike Alan, who was an advocate for himself (which meant that he avoided incorrect chemotherapy, got doctors to look at tests they would have missed, and had doctors collaborating in ways that they otherwise might not have) and who also enlisted one of our colleagues in the biology department to help him sort through the information he was receiving.

Here’s an instance of heroine Sophia Western benefitting from a patient advocate, who saves her from an unnecessary bloodletting. The advocate is her father, who makes sure that the doctor handles her with far more care and sensitivity than he handles Tom:

While the servants were busied in providing materials, the surgeon, who imputed the backwardness which had appeared in Sophia to her fears, began to comfort her with assurances that there was not the least danger; for no accident, he said, could ever happen in bleeding, but from the monstrous ignorance of pretenders to surgery, which he pretty plainly insinuated was not at present to be apprehended. Sophia declared she was not under the least apprehension; adding, “If you open an artery, I promise you I’ll forgive you.” “Will you?” cries Western: “D–n me, if I will. If he does thee the least mischief, d–n me if I don’t ha’ the heart’s blood o’un out.” The surgeon assented to bleed her upon these conditions, and then proceeded to his operation, which he performed with as much dexterity as he had promised; and with as much quickness: for he took but little blood from her, saying, it was much safer to bleed again and again, than to take away too much at once.

Doctorspeak

I end this post with one final satirical jab that goes after doctorspeak, doctor equivocation, and doctor greed. It’s lengthy but you may find it enjoyable. I like the part where a friend of Tom’s, after having listened to a supposedly learned disquisition about Tom’s injury and asked if he has followed it, replies, “I cannot say I understand a syllable.” Here it is:

She [the landlady] was proceeding in this manner when the surgeon entered the room. The lieutenant immediately asked how his patient did. But he resolved him only by saying, “Better, I believe, than he would have been by this time, if I had not been called; and even as it is, perhaps it would have been lucky if I could have been called sooner.”–“I hope, sir,” said the lieutenant, “the skull is not fractured.”–“Hum,” cries the surgeon: “fractures are not always the most dangerous symptoms. Contusions and lacerations are often attended with worse phanomena, and with more fatal consequences, than fractures. People who know nothing of the matter conclude, if the skull is not fractured, all is well; whereas, I had rather see a man’s skull broke all to pieces, than some contusions I have met with.”–“I hope,” says the lieutenant, “there are no such symptoms here.”–“Symptoms,” answered the surgeon, “are not always regular nor constant. I have known very unfavorable symptoms in the morning change to favourable ones at noon, and return to unfavorable again at night. Of wounds, indeed, it is rightly and truly said, Nemo repente fuit turpissimus. I was once, I remember, called to a patient who had received a violent contusion in his tibia, by which the exterior cutis was lacerated, so that there was a profuse sanguinary discharge; and the interior membranes were so divellicated, that the os or bone very plainly appeared through the aperture of the vulnus or wound. Some febrile symptoms intervening at the same time (for the pulse was exuberant and indicated much phlebotomy), I apprehended an immediate mortification. To prevent which, I presently made a large orifice in the vein of the left arm, whence I drew twenty ounces of blood; which I expected to have found extremely sizy and glutinous, or indeed coagulated, as it is in pleuretic complaints; but, to my surprise, it appeared rosy and florid, and its consistency differed little from the blood of those in perfect health. I then applied a fomentation to the part, which highly answered the intention; and after three or four times dressing, the wound began to discharge a thick pus or matter, by which means the cohesion–But perhaps I do not make myself perfectly well understood?”–“No, really,” answered the lieutenant, “I cannot say I understand a syllable.”–“Well, sir,” said the surgeon, “then I shall not tire your patience; in short, within six weeks my patient was able to walk upon his legs as perfectly as he could have done before he received the contusion.”–“I wish, sir,” said the lieutenant, “you would be so kind only to inform me, whether the wound this young gentleman hath had the misfortune to receive, is likely to prove mortal.”–“Sir,” answered the surgeon, “to say whether a wound will prove mortal or not at first dressing, would be very weak and foolish presumption: we are all mortal, and symptoms often occur in a cure which the greatest of our profession could never foresee.”–“But do you think him in danger?” says the other.–“In danger! ay, surely,” cries the doctor: “who is there among us, who, in the most perfect health, can be said not to be in danger? Can a man, therefore, with so bad a wound as this be said to be out of danger? All I can say at present is, that it is well I was called as I was, and perhaps it would have been better if I had been called sooner. I will see him again early in the morning; and in the meantime let him be kept extremely quiet, and drink liberally of water-gruel.”–“Won’t you allow him sack-whey?” said the landlady.–“Ay, ay, sack-whey,” cries the doctor, “if you will, provided it be very small.”–“And a little chicken broth too?” added she.–“Yes, yes, chicken broth,” said the doctor, “is very good.”–“Mayn’t I make him some jellies too?” said the landlady.–“Ay, ay,” answered the doctor, “jellies are very good for wounds, for they promote cohesion.” And indeed it was lucky she had not named soup or high sauces, for the doctor would have complied, rather than have lost the custom of the house.

One Trackback

[…] Satirizing Doctors, the Best Medicine […]