Monday

When I was teaching Midnight’s Children recently, I challenged my students to set Salman’s Rushdie’s characters in the United States. Although post-colonial India is, of course, nothing like America, the author provides a useful framework for understanding some of our political mysteries, including our vertigo-inducing shift from Barack Obama to Donald Trump. Rushdie has insights into how societies normalize authoritarian behavior and (I say this thinking of the Parkland, Florida activists) points to the hopeful future that reality-hardened young people can help bring about.

Midnight’s Children imagines that the children born between midnight and one on India’s independence day (August 15, 1947) have special powers. Saleem Sinai, the book’s narrator, can telepathically link all the other children, which he proceeds to do when they all reach ten.

Some background on India is useful. To function as a nation, India must juggle over 2000 ethnicities and 22 different languages. When Great Britain ruled the country, it provided an illusory unity, if only by giving Indians a common enemy. (As Saleem writes of his grandfather, he started off as a Kashmiri but became Indian after a British massacre.) Once the English departed, however, the country immediately split into India and Pakistan, and it has periodically experienced language riots, attacks on others ethnicities by Hindu militants (Hindus comprise 80% of the population, Muslims 14%), and other internal difficulties.

Saleem dreams that, by talking to each other (through him), the midnight children will be able to create a loose federalism that will save the nation. He believes this mission has been given to him by India’s first prime minister, Jawaharial Nehru, who writes him a letter upon his birth:

Dear Baby Saleem,

My belated congratulations on the happy accident of your moment of birth! You are the newest bearer of that ancient face of India which is also eternally young. We shall be watching over your life with the closest attention; it will be, in a sense, the mirror of our own.

Saleem inherits his multicultural vision from his grandfather Aadam Aziz, who once dreamed of keeping Pakistan and India together. Inspired by a charismatic federalist advocate known as “the Hummingbird,” Aziz catches what Saleem calls “the optimism disease”—a disease because it naively relies on the better angels of our nature. Islamic fundamentalists soon put an end to the disease by assassinating Hummingbird.

Saleem’s vision has affinities with Obama’s “not red states or blue states but the United States” (itself a version of “e pluribus unum” that is foundational to our nation). Saleem quickly discovers the same problems that Obama did:

Children, however magical, are not immune to their parents; and as the prejudices and world-views of adults began to take over their minds, I found children from Maharashtra loathing Gujaratis, and fair-skinned northerners reviling Dravidian ‘blackies’; there were religious rivalries; and class entered our councils. The rich children turned up their noses at being in such lowly company; Brahmins began to feel uneasy at permitting even their thoughts to touch the thoughts of untouchables; while, among the low-born, the pressures of poverty and Communism were becoming evident… and, on top of all this, there were clashes of personality, and the hundred squalling rows which are unavoidable in a parliament composed entirely of half-grown brats.

In this way the Midnight Children’s Conference fulfilled the prophecy of the Prime Minister and became, in truth, a mirror of the nation

One child resists the Midnight’s Children Conference from the first, and he is important to understand in the contrast that I draw between Obama and Trump. Shiva, like Saleem, is born on the stroke of midnight, and, through a set of circumstances, is switched at birth with him. So Shiva, who should grow up in wealthy Islamic family, instead is raised in an impoverished Hindu one, and vice versa for Saleem. Rushdie plays with the mix-up throughout the novel, essentially seeing Shiva and Saleem as two sides of India. Saleem is the dream of a generous, multicultural nation, Shiva of an angry and divided one. Here’s Shiva pooh-poohing Saleem’s vision in one of their nightly conferences:

‘Brothers, sisters!’ I broadcast, with a mental voice as uncontrollable as its physical counterpart, ‘Do not let this happen! Do not permit the endless duality of masses-and-classes, capital-and-labour, them-and-us to come between us! We,’ I cried passionately, ‘must be a third principle, we must be the force which drives between the horns of the dilemma; for only by being other, by being new, can we fulfil the promise of our birth!’… But I could hear, behind my anxious broadcast, the amused laughter of my greatest rival; and there was Shiva in all our heads, saying scornfully, ‘No, little rich boy; there is no third principle; there is only money-and-poverty, and have-and-lack, and right-and-left; there is only me-against-the-world! The world is not ideas, rich boy; the world is no place for dreamers or their dreams; the world, little Snotnose, is things. Things and their makers rule the world…

Shiva will go on to dismiss Saleem’s idealism as “mush, like overcooked rice. Sentimental as a grandmother.”

America has learned these truths about itself over the past 10 years. We are both a country that welcomes the diversity of immigrants and a parochial one that lashes out against people not like ourselves. Saleem/Shiva represents the duality that we see in Obama/Trump.

Shiva, named for the Hindu god of destruction (also of creation but hold that thought for a moment), goes on to become a terrifying military figure who ultimately rounds up the midnight children and deprives them of their special powers, thereby ending Saleem’s federalist dream. Shiva works for Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, whose authoritarian seizure of power in 1976 spelled the end (in Rushdie’s mind) of India’s hopes. Rushdie uses Gandhi’s program of sterilization (8.3 million people were sterilized, most of them unwillingly) as a metaphor for the death of a hope.

The horror of Gandhi’s “emergency measures” become quickly normalized, an unsettling indication of how a nation can accept the once unthinkable. When Saleem returns to a reconstituted magicians’ ghetto after Shiva has broken it up and sterilized its members, he discovers that people can’t remember how they used to be:

[I]t rapidly became clear that the magicians, too, were losing their memories. Somewhere in the many moves of the peripatetic slum, they had mislaid their powers of retention, so that now they had become incapable of judgment, having forgotten everything to which they could compare anything that happened. Even the Emergency was rapidly being consigned to the oblivion of the past, and the magicians concentrated upon the present with the monomania of snails. Nor did they notice that they had changed; they had forgotten that they had ever been otherwise, Communism had seeped out of them and been gulped down by the thirsty, lizard-quick earth; they were beginning to forget their skills in the confusion of hunger, disease, thirst and police harassment which constituted (as usual) the present.

And yet, somehow, Saleem’s federalist vision survives and in ways from which Trump-discouraged Americans can draw hope. Although Saleem is sterilized, he has a son (actually he’s Shiva’s son but raised by Saleem in another one of the novel’s reversals), and young Aadam represents new possibility. Think of him as one of the Parkland, Florida teens:

I understood once again that Aadam was a member of a second generation of magical children who would grow up far tougher than the first, not looking for their fate in prophecy or the stars, but forging it in the implacable furnaces of their wills. Looking into the eyes of the child who was simultaneously not-my-son and also more my heir than any child of my flesh could have been, I found in his empty, limpid pupils a second mirror of humility, which showed me that, from now on, mine would be as peripheral a role as that of any redundant oldster: the traditional function, perhaps, of reminiscer, of teller-of-tales… I wondered if all over the country the bastard sons of Shiva were exerting similar tyrannies upon hapless adults, and envisaged for the second time that tribe of fearsomely potent kiddies, growing waiting listening, rehearsing the moment when the world would become their plaything.

Shiva, in spite of himself, has fathered young people throughout the land (Aadam is not the only one) who may save India from Ghandi’s authoritarian rule. Perhaps Trump, also in spite of himself, has given rise to the young people who will finally bring about sensible gun control, universal healthcare, protections against sexual harassment, and other progressive developments.

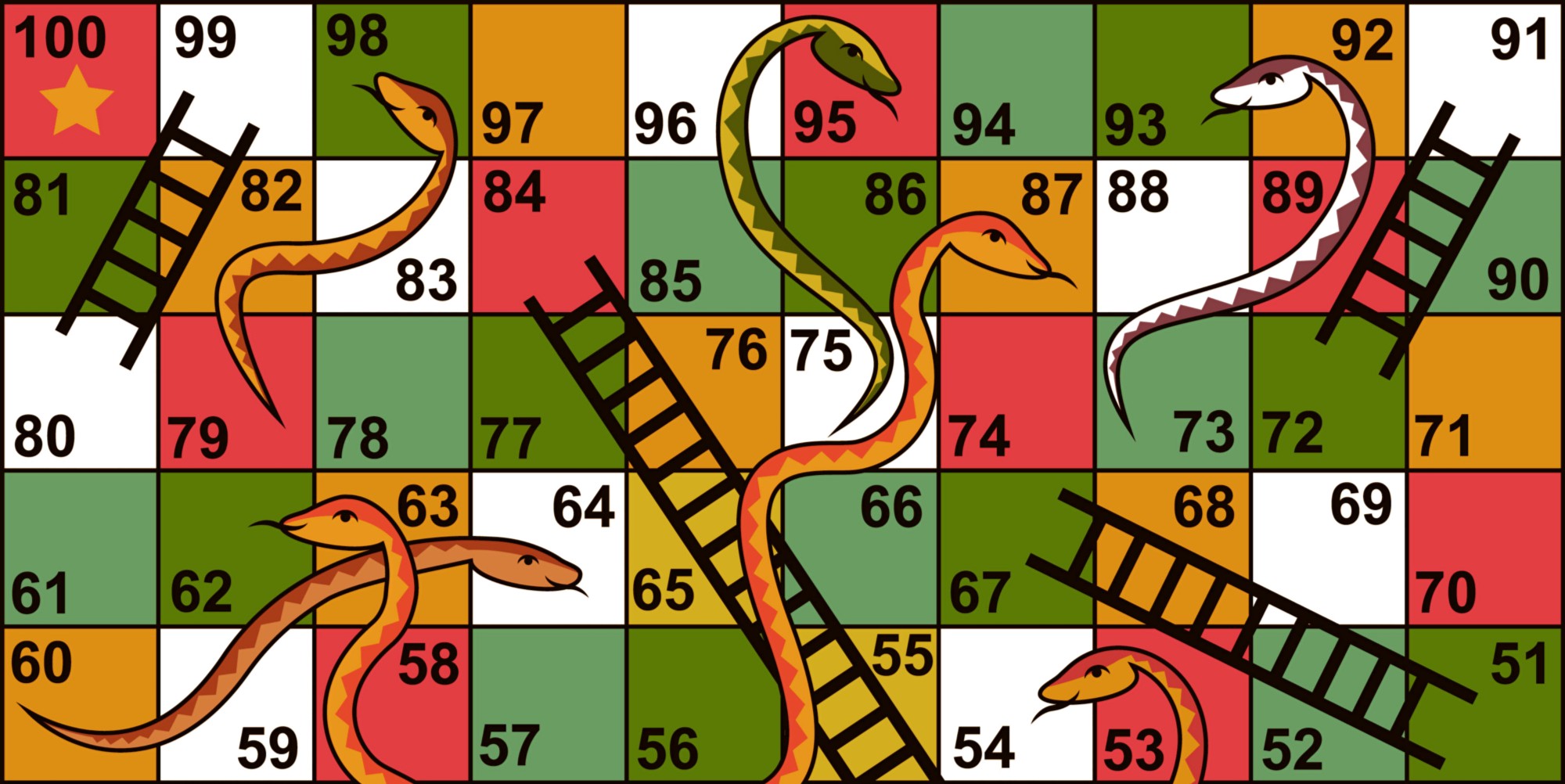

This would be in a line with a game that Saleem loves as a child called “Snakes and Ladders.” The game captures reversals of fortune, both in the novel and in our politics, and to it Saleem adds one crucial dimension: sometimes a snake can function as a ladder and a ladder as a snake:

All games have morals; and the game of Snakes and Ladders captures, as no other activity can hope to do, the eternal truth that for every ladder you climb, a snake is waiting just around the corner; and for every snake, a ladder will compensate. But it’s more than that; no mere carrot-and-stick affair; because implicit in the game is the unchanging twoness of things, the duality of up against down, good against evil; the solid rationality of ladders balances the occult sinuosities of the serpent; in the opposition of staircase and cobra we can see, metaphorically, all conceivable oppositions, Alpha against Omega…[B]ut I found, very early in my life, that the game lacked one crucial dimension, that of ambiguity–because, as events are about to show, it is also possible to slither down a ladder and climb to triumph on the venom of a snake…

Right now, Trump strikes many of us as a snake. In Saleem’s world, however, snakes don’t always get the last laugh.

Additional note: In a recent post I reported on Rusdie’s Golden House, which my book discussion group read. Rushdie brings his novelist’s eye to the 2016 American election. My group agreed that the book doesn’t really work, however. The explosive imagination that gave us Saleem and Shiva is missing and we don’t learn much we didn’t already know.