Friday

After today, I’ll stop writing posts about how Donald Trump conned his way into the American presidency. From here on out, we’ll be dealing with a man who is president and so will be able to focus on his actual body of work. The reality show is about to end as reality itself walks through the door.

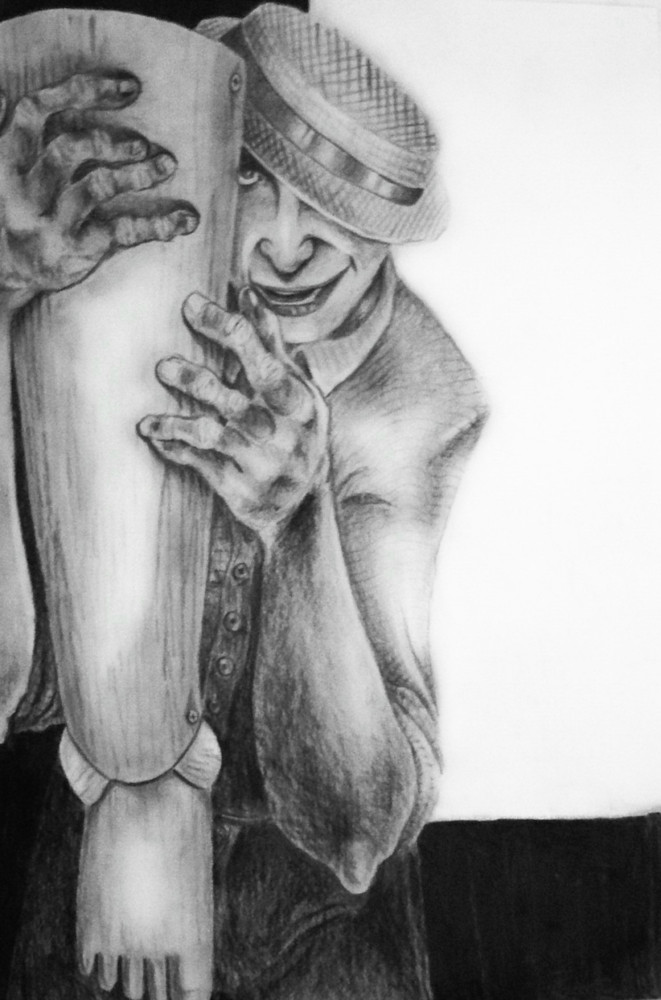

Today’s literary parallel was suggested to me by my colleague Ben Click and it’s a good one: Donald Trump is the Bible salesman in Flannery O’Connor’s “Good Country People.”

In the story, an intellectual snob with a wooden leg—her name is Joy but she has renamed herself Hulga—is sure that the salesman is just a Christian hick (a.k.a. a good ol’ country boy) and she looks down on him.

Like the American media with Trump in the early days, she thinks she can amuse herself with him and takes him to a hayloft. He knows how to play her and her superiority complex, however. While making love to her, he gets her to open up to him and reveal how she attaches her wooden leg.

This startling request makes her think they are reaching new levels of intimacy, and she dreams of a future together: “She was thinking that she would run away with him and that every night he would take the leg off and every morning put it back on again.”

What happens to her next is what, I predict, is about to happen to those who think they can bend Trump to their will. The Bible salesman is actually someone who has fun spitting in the faces of people who feel superior to him. With Hulga, he first reveals that his carrying case contains whiskey and pornographic playing cards, not Bibles. Then he steals her leg:

Her voice when she spoke had an almost pleading sound. “Aren’t you,” she murmured, “aren’t you just good country people?”

The boy cocked his head. He looked as if he were just beginning to understand that she might be trying to insult him. “Yeah,” he said, curling his lip slightly, “but it ain’t held me back none. I’m as good as you any day in the week.”

“Give me my leg,” she said.

He pushed it farther away with his foot. “Come on now, let’s begin to have us a good time,” he said coaxingly. “We ain’t got to know one another good yet.”

As he leaves through the trap door, she learns that she’s not the first person he has conned:

When all of him had passed but his head, he turned and regarded her with a look that no longer had any admiration in it. “I’ve gotten a lot of interesting things,” he said. “One time I got a woman’s glass eye this way. And you needn’t to think you’ll catch me because Pointer ain’t really my name. I use a different name at every house I call at and don’t stay nowhere long. And I’ll tell you another thing, Hulga,” he said, using the name as if he didn’t think much of it, “you ain’t so smart. I been believing in nothing ever since I was born!” and then the toast-colored hat disappeared down the hole and the girl was left, sitting on the straw in the dusty sunlight.

Pointer operates out a deep well of resentment. He cons simply to show people up, and he loves to rub his victims’ face in their defeat. He believes in nothing but that.

Establishment Republicans, the media, and liberals all underestimated Trump. Republicans thought they could use him to deliver certain voters to the GOP; the media used him to deliver readers and viewers; and liberals thought that he was so outrageous that he would ensure the election of a Democrat. They’re all hobbling around on one leg down. O’Connor’s lesson appears to be that, whenever you think you have the upper hand with a con man, that’s the very moment when you’re about to get taken for a ride.