Monday

My mother, in her weekly literature column for the local newspaper, had the inspired idea to include a couple of passages from The House at Pooh Corner to mark the beginning of the school year. I borrow her idea here.

In the first passage, the animals are in an uproar because a mysterious sign has appeared on Christopher Robin’s door. No one know how Christopher Robin is spending his mornings, but the notice soon has them looking for a “Spotted or Herbaceous Backson”:

GON OUT

BACKSON

BISY

BACKSON

C. R.

Eeyore knows, however, that Christopher Robin is off at school, and he himself is trying to become educated, as he explains to Piglet:

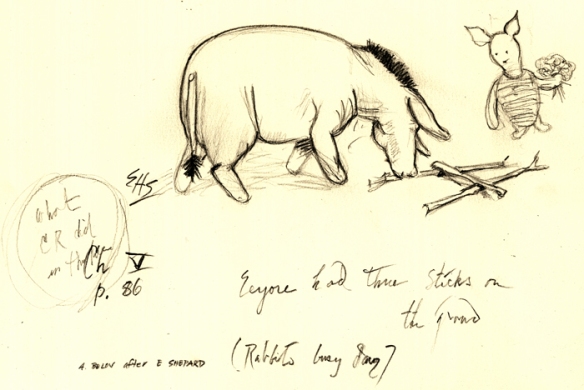

Eeyore had three sticks on the ground, and was looking at them. Two of the sticks were touching at one end, but not at the other, and the third stick was laid across them. Piglet thought that perhaps it was a Trap of some kind.

“Oh, Eeyore,” he began again, “I just–“

“Is that little Piglet?” said Eeyore, still looking hard at his sticks.

“Yes, Eeyore, and I–“

“Do you know what this is?”

“No,” said Piglet.

“It’s an A.”

“Oh,” said Piglet.

“Not O–A,” said Eeyore severely. “Can’t you hear, or do you think you have more education than Christopher Robin?”

“Yes,” said Piglet. “No,” said Piglet very quickly. And he came closer still.

“Christopher Robin said it was an A, and an A it is–until somebody treads on it,” Eeyore added sternly.

Eeyore’s moment of triumph, which proves to be short-ived, occurs when he is able to inform Rabbit of Christopher Robin’s whereabouts:

What does Christopher Robin do in the mornings? He learns. He becomes Educated. He instigorates–I think that is the word he mentioned, but I may be referring to something else–he instigorates Knowledge. In my small way I also, if I have the word right, am–am doing what he does.

The triumph, as I say, is short-lived when Eeyore discovers that Rabbit is already educated:

“That, for instance, is?”

“An A,” said Rabbit, “but not a very good one. Well, I must get back and tell the others.”

Eeyore looked at his sticks and then he looked at Piglet.

“What did Rabbit say it was?” he asked.

“An A,” said Piglet.

“Did you tell him?”

“No, Eeyore, I didn’t. I expect he just knew.”

“He knew? You mean this A thing is a thing Rabbit knew?”

“Yes, Eeyore. He’s clever, Rabbit is.”

“Clever!” said Eeyore scornfully, putting a foot heavily on his three sticks. “Education!” said Eeyore bitterly, jumping on his six sticks. “What is Learning?” asked Eeyore as he kicked his twelve sticks into the air. “A thing Rabbit knows! Ha!”

So much for education.

The other passage occurs at the end of the book, where we see Milne, through Christopher Robin and Pooh, dreaming of an endless summer that isn’t interrupted by schooling. It reminds me of the Wordsworth poem “The Tables Turned”:

Up! up! my Friend, and quit your books;

Or surely you’ll grow double:

Up! up! my Friend, and clear your looks;

Why all this toil and trouble?

The sun above the mountain’s head,

A freshening lustre mellow

Through all the long green fields has spread,

His first sweet evening yellow.

Books! ’tis a dull and endless strife:

Come, hear the woodland linnet,

How sweet his music! on my life,

There’s more of wisdom in it.

And hark! how blithe the throstle sings!

He, too, is no mean preacher:

Come forth into the light of things,

Let Nature be your teacher.

She has a world of ready wealth,

Our minds and hearts to bless—

Spontaneous wisdom breathed by health,

Truth breathed by cheerfulness.

One impulse from a vernal wood

May teach you more of man,

Of moral evil and of good,

Than all the sages can.

Sweet is the lore which Nature brings;

Our meddling intellect

Mis-shapes the beauteous forms of things:—

We murder to dissect.

Enough of Science and of Art;

Close up those barren leaves;

Come forth, and bring with you a heart

That watches and receives.

In the Pooh passage, Christopher Robin tells his faithful companion that what he likes doing best “is nothing.” They are sitting in an enchanted wood, which Christopher Robin knows is enchanted because it resists the tyranny of mathematics:

“How do you do Nothing?” asked Pooh, after he had wondered for a long time.

“Well, it’s when people call out at you just as you’re going off to do it ‘What are you going to do, Christopher Robin?’ and you say ‘Oh, nothing,’ and then you go and do it.”

“Oh, I see,” said Pooh.

“This is a nothing sort of thing that we’re doing now.”

“Oh, I see,” said Pooh again.

“It means just going along, listening to all the things you can’t hear, and not bothering.”

“Oh!” said Pooh.

They walked on, thinking of This and That, and by-and-by they came to an enchanted place on the very top of the Forest called Galleons Lap, which is sixty-something trees in a circle; and Christopher Robin knew that it was enchanted because nobody had ever been able to count whether it was sixty-three or sixty-four, not even when he tied a piece of string round each tree after he had counted it. Being enchanted, its floor was not like the floor the Forest, gorse and bracken and heather, but close-set grass, quiet and smooth and green. It was the only place in the Forest where you could sit down carelessly, without getting up again almost at once and looking for somewhere else. Sitting there they could see the whole world spread out until it reached the sky, and whatever there was all the world over was with them in Galleons Lap.

Suddenly Christopher Robin began to tell Pooh about some of the things: People called Kings and Queens and something called Factors, and a place called Europe, and an island in the middle of the sea where no ships came, and how you make a Suction Pump (if you want to), and when Knights were Knighted, and what comes from Brazil. And Pooh, his back against one of the sixty-something trees and his paws folded in front of him, said “Oh!” and “I didn’t know,” and thought how wonderful it would be to have a Real Brain which could tell you things. And by-and-by Christopher Robin came to an end of the things, and was silent, and he sat there looking out over the world, and wishing it wouldn’t stop.

This is also Milne wishing that childhood wouldn’t stop. Schooling, in this vision, represents an end to innocence. For the author of the Pooh stories, at this moment it is enough to have a heart that watches and receives.

I’ll note that my father, who raised me on Pooh and had a Milne-like longing for innocence, never read the final chapter to me. He found it too sad.