Spiritual Sunday

On the recommendation of Jane Austen, I am reading Samuel Richardson’s Sir Charles Grandison (1753), reportedly her favorite novel. While it was slow going at first (as I expected), I’ve just read a dazzling takedown of toxic masculinity. I write about it in today’s column because issues of Christian belief arise.

I’m also finding Grandison fascinating because it appears to be a response to Henry Fielding’s Tom Jones, which used to be my favorite novel. Both grapple with what makes for an ideal man while arriving at different conclusions. Some background on the Richardson-Fielding relationship is useful here before I elaborate.

Richardson’s first work, Pamela, like his other works, is an epistolary novel (conveyed through letters). In it, servant girl Pamela fights off seduction attempts by her employer, Lord B, eventually impressing him so much with her virtue that he marries her. In a sequel we learn about their children (Pamela in her Exalted Condition). Some consider Pamela to be the first English novel.

Put off by Pamela’s incessant references to her virtue, Fielding wrote a parody, Shamela, in which Pamela cynically leverages this “vartue” (as she puts it) to entrap Lord B, now become Lord Booby. While his entry into fiction began with parody, Fielding became so entranced with narrative fiction that he wrote a follow-up work about Pamela’s brother, Joseph Andrews, which is closer to what we think of as a novel. This in turn paved the way for Tom Jones.

Meanwhile, however, an understandable feud had arisen between Richardson and Fielding. As a printer and middle-class businessman, Richardson felt particularly vulnerable to being mocked by a member of the gentry, and it didn’t help when Fielding (along with many other readers) begged him to change the destined end of his next novel, Clarissa, which appeared in installments. Clarissa never does yield to the rake who has abducted her, nor did Richardson yield to his readers, and she dies in the end. The suspense is so intense in the course of Clarissa’s million words that women all over England disappeared into their private rooms (known as closets) for days on end to read it, abandoning household duties and upsetting their husbands.

Fielding at least was no longer satirizing Richardson—he was as caught up in the story as everyone else—but Richardson still couldn’t have taken Fielding’s intervention kindly. He may also have felt aggrieved when his own sensation was eclipsed just over a year later by Fielding’s masterpiece Tom Jones.

All of this I offer as background for today’s discussion. I’m convinced that, just as Shamela and Joseph Andrews are responses to Pamela, so Sir Charles Grandison is a response to Tom Jones, at least in part. I think Richardson saw men, including Fielding, as trapped in a culture of toxic masculinity and tried, through Grandison, to imagine a new kind of man. The issue is most clearly seen in attitudes towards dueling.

A scene in Tom Jones has Tom calling the execrable soldier Northerton “one of the most impudent rascals upon earth” for having besmirched his fair Sophia, at which point Northerton knocks him out with a bottle of wine. So affronted, Tom, although confined to a sick bed, is determined to fight a duel. As he and most men of the age would see it, both his honor and Sophia’s are at stake.

The lieutenant readily agrees. Tom, on the other hand, has some qualms. Is it right, he wonders for a Christian to engage in duels? “[T]hough I have been a very wild young fellow, still in my most serious moments, and at the bottom, I am really a Christian,” he tells the officer. The officer replies that, if he had to choose between Christ and his honor, he would choose honor. Here’s their interchange:

“But how terrible must it be,” cries Jones, “to anyone who is really a Christian, to cherish malice in his breast, in opposition to the command of Him who hath expressly forbid it? How can I bear to do this on a sickbed? Or how shall I make up my account, with such an article as this in my bosom against me?”

“Why, I believe there is such a command,” cries the lieutenant; “but a man of honor can’t keep it. And you must be a man of honor, if you will be in the army. I remember I once put the case to our chaplain over a bowl of punch, and he confessed there was much difficulty in it; but he said, he hoped there might be a latitude granted to soldiers in this one instance; and to be sure it is our duty to hope so; for who would bear to live without his honor? No, no, my dear boy, be a good Christian as long as you live; but be a man of honor too, and never put up an affront; not all the books, nor all the parsons in the world, shall ever persuade me to that. I love my religion very well, but I love my honor more.

The lieutenant then wonders whether a textual problem accounts for the apparent contradiction:

There must be some mistake in the wording the text, or in the translation, or in the understanding it, or somewhere or other. But however that be, a man must run the risk, for he must preserve his honor. So compose yourself to-night, and I promise you you shall have an opportunity of doing yourself justice.”

In other words, Biblical scholars have somehow mistranslated “love they neighbor” and “turn the other cheek.” While the lieutenant may be satisfied with his reasoning, however, Tom continues to mull the question, even though eventually he makes the same choice:

“Very well,” said he, “and in what cause do I venture my life? Why, in that of my honour. And who is this human being? A rascal who hath injured and insulted me without provocation. But is not revenge forbidden by Heaven? Yes, but it is enjoined by the world. Well, but shall I obey the world in opposition to the express commands of Heaven? Shall I incur the Divine displeasure rather than be called—ha—coward—scoundrel?—I’ll think no more; I am resolved, and must fight him.”

Richardson could very well have this exact scene in mind when he has Grandison explain how a man can maintain his honor and refuse a duel both. If Richardson can convincingly pull this off, then Grandison is a more admirable protagonist than Tom, at least in this respect.

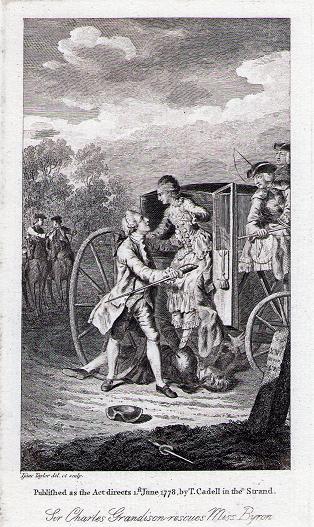

The situation is as follows. Sir Hargrave, in love with Henrietta Byron, abducts her with the intent of a forced marriage after she turns down his proposal. Coming upon their carriage and hearing her cries for help, Grandison rescues her, knocking out a couple of Hargrave’s teeth in the process. (He himself receives a slight rapier wound from Hargrave but manages to disarm him without the use of his own sword.) Feeling aggrieved, Hargrave challenges him to a duel but Grandison turns him down. In a letter he explains the reasons why:

My answer is this—I have ever refused (and the occasion has happened too often) to draw my sword upon a set and formal challenge. Yet I have reason to think, from the skill I pretend to have in the weapons, that in declining to do so, I consult my conscience rather than my safety.

Have you any friends, Sir Hargrave? Do they love you? Do you love them? Are you desirous of life for their sakes? for your own?—Have you enemies to whom your untimely end would give pleasure?—Let these considerations weigh with you: They do, and always did, with me. I am cool: You cannot be so. The cool person, on such an occasion as this, should put the warm one on thinking: This however as you please.

But one more question let me ask you—If you think I have injured you, is it prudent to give me a chance, were it but a chance, to do you a still greater injury?

Unsatisfied by the letter, Hargrave invites Grandison to a breakfast, where in front of friends he tries to provoke him to fight. Again he proves unsuccessful as Grandison insists he will only use his sword in self-defense. Then he startles Hargrave by contending he is his “best friend”:

Sir Har. “My best friend,” Sir!

Sir Ch. Yes, Sir. If either the preservation of your own life, or the saving you a long regret for taking that of another, as the chance might have been, deserves your consideration.

And when Hargrave proclaims that he is ready to “die like a man of honor,” Grandison replies, “To die like a man of honor, Sir Hargrave, you must have lived like one.”

By the end, Grandison has impressed Hargrave’s friends, if not Hargrave himself. “We all acknowledge dueling to be criminal,” says one of them. “But no one has the courage to break through a bad custom.” When they ask how he arrived at his understanding, Grandison credits his mother:

My Mother was an excellent woman: She had instilled into my earliest youth, almost from infancy, notions of moral rectitude, and the first principles of Christianity; now rather ridiculed than inculcated in our youth of condition. She was ready sometimes to tremble at the consequences, which she thought might follow from the attention which I paid (thus encouraged and applauded) to this practice; and was continually reading lectures to me upon true magnanimity, and upon the law of kindness, benevolence, and forgiveness of injuries.

Grandison concludes that the “doctrine of returning good for evil” is the noblest and most heroic of doctrines..

I’ve only completed the first two of Grandison’s six volumes but am seeing why Austen appreciates it. When it comes to dueling, I can think of her mentioning only one (Brandon’s duel with Willoughby for ruining his ward), and Elinor Dashwood does not approve of it. Austen’s male protagonists–I’m thinking of Henry Tilney, Edward Ferrars, Edmund Bertram—resemble Grandison more than Jones.

We also can take note of who prefers which novel in Northanger Abbey. The thuggish John Thorpe is a fan of Tom Jones, perhaps because of Tom’s drinking and womanizing, while his conniving sister Isabelle finds Sir Charles Grandison to be “an amazing, horrid book. (Isabella is no Harriet Byron and would say yes to the wealthy Sir Hargrave in a heartbeat.) By contrast, heroine Catherine Moreland finds Grandison “very entertaining,” as does her laudable mother.

I don’t like Grandison as much as I do Clarissa, but my esteem for Richardson has grown whereas Fielding has dropped a bit in my estimation. There’s too much of a “boys will be boys” philosophy in his novel, even though he voices an appropriate horror for libertines. Richardson, on the other hand, grapples with the very contemporary issue of toxic masculinity in ways that I find remarkable.