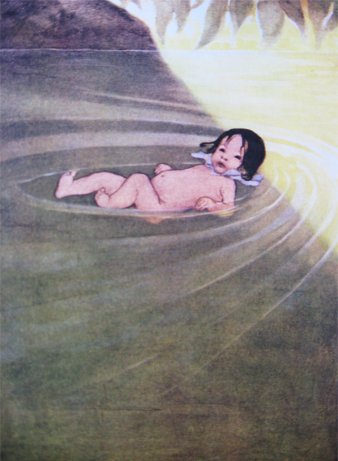

Last week I played the doting grandfather and recounted how I took my grandson Alban to the zoo. Today you must hear how I went swimming with my granddaughters Esmé and Etta on a Memorial Day family reunion. A. A. Milne provided the framing poem for Alban while Charles Kingsley’s Water Babies has supplied me with images for my time in the pool with the girls.

Kingsley’s 1863 children’s novel tells the story of Tom the chimneysweep, a figure lifted from William Blake. Mistreated by his master and then falsely accused of a theft, Tom becomes a fugitive. Eventually he falls into a river and drowns, at which point he becomes a water baby, complete with “a pretty little lace-collar of gills about his neck, as lively as a grig, and as clean as a fresh-run salmon.” Life becomes much better at this point:

Tom was quite alive; and cleaner, and merrier, than he ever had been. The fairies had washed him, you see, in the swift river, so thoroughly, that not only his dirt, but his whole husk and shell had been washed quite off him, and the pretty little real Tom was washed out of the inside of it, and swam away, as a caddis does when its case of stones and silk is bored through, and away it goes on its back, paddling to the shore, there to split its skin, and fly away as a caperer, on four fawn-coloured wings, with long legs and horns. They are foolish fellows, the caperers, and fly into the candle at night, if you leave the door open. We will hope Tom will be wiser, now he has got safe out of his sooty old shell.

The pure joy of my granddaughters in the water is captured in Water Babies, leading me to conclude that Kingsley is remembering his own childhood swimming:

Tom was very happy in the water. He had been sadly overworked in the land-world; and so now, to make up for that, he had nothing but holidays in the water-world for a long, long time to come. He had nothing to do now but enjoy himself, and look at all the pretty things which are to be seen in the cool clear water-world, where the sun is never too hot, and the frost is never too cold.

Kingsley was a fan of Darwin’s Origin of the Species and his waterworld is filled with biological marvels:

Tom used to play with [the trout] at hare and hounds, and great fun they had; and he used to try to leap out of the water, head over heels, as they did before a shower came on; but somehow he never could manage it. He liked most, though, to see them rising at the flies, as they sailed round and round under the shadow of the great oak, where the beetles fell flop into the water, and the green caterpillars let themselves down from the boughs by silk ropes for no reason at all; and then changed their foolish minds for no reason at all either; and hauled themselves up again into the tree, rolling up the rope in a ball between their paws; which is a very clever rope-dancer’s trick…

It is fairly clear that The Water Babies influenced James Barrie’s Peter Pan, and Kingsley has choice words for those Grandgrindians who have lost touch with a child’s imagination:

Now if you don’t like my story, then go to the schoolroom and learn your multiplication table, and see if you like that better. Some people, no doubt, would do so. So much the better for us, if not for them. It takes all sorts, they say, to make a world.

Once of these people, standing in for one-dimensional positivist science, refuses to acknowledge Tom when he catches him in a bucket. His granddaughter instantly recognizes him as a water baby but the professor, in thrall to his theories, can’t admit what he’s seeing. Note that, while a Darwin fan, Kingsley would not approve of evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins, the outspoken atheist and materialist. Kingsley sees both God and the imagination as an integral part of the world:

Now, if the professor had said to Ellie, “Yes, my darling, it is a water-baby, and a very wonderful thing it is; and it shows how little I know of the wonders of nature, in spite of forty years’ honest labor. I was just telling you that there could be no such creatures; and, behold! here is one come to confound my conceit and show me that Nature can do, and has done, beyond all that man’s poor fancy can imagine. So, let us thank the Maker, and Inspirer, and Lord of Nature for all His wonderful and glorious works, and try and find out something about this one;” – I think that, if the professor had said that, little Ellie would have believed him more firmly, and respected him more deeply, and loved him better, than ever she had done before. But he was of a different opinion. He hesitated a moment. He longed to keep Tom, and yet he half wished he never had caught him; and at last he quite longed to get rid of him. So he turned away and poked Tom with his finger, for want of anything better to do; and said carelessly, “My dear little maid, you must have dreamt of water-babies last night, your head is so full of them.”…

And this is why they say that no one has ever yet seen a water-baby. For my part, I believe that the naturalists get dozens of them when they are out dredging; but they say nothing about them, and throw them overboard again, for fear of spoiling their theories.

Even if you believe in water babies, Kingsley has a good explanation why you might never have seen one:

Only where men are wasteful and dirty, and let sewers run into the sea instead of putting the stuff upon the fields like thrifty reasonable souls; or throw herrings’ heads and dead dog-fish, or any other refuse, into the water; or in any way make a mess upon the clean shore –there the water-babies will not come, sometimes not for hundreds of years (for they cannot abide anything smelly or foul), but leave the sea-anemones and the crabs to clear away everything, till the good tidy sea has covered up all the dirt in soft mud and clean sand, where the water-babies can plant live cockles and whelks and razor-shells and sea-cucumbers and golden-combs, and make a pretty live garden again, after man’s dirt is cleared away. And that, I suppose, is the reason why there are no water-babies at any watering-place which I have ever seen.

I think it appropriate that Esmé and Etta should remind me of Water Babies since their father’s first academic publication, appearing in Victorian Studies, analyzes the work. In a side note, I add that it’s possible that my great-grandmother was once in close proximity to Kingsley. That’s because her father, before immigrating to the United States, was estate caretaker for a Lord Bunberry (believe it or not, he is not just an Oscar Wilde invention) and Kingsley visited the estate when Eliza Scott (later Fulcher) was a little girl.

Toby argues in his article that amongst Kingsley’s many targets is mechanized education. The author wanted children’s imaginations to roam wild and free. Thanks to his own imagination and the imaginations of contemporaries such as Lewis Carroll, Charles Dickens, George MacDonald, Christine Rossetti, and Edward Lear, Toby and I are better able to enter into Esmé and Etta’s rich interior worlds.