Thursday

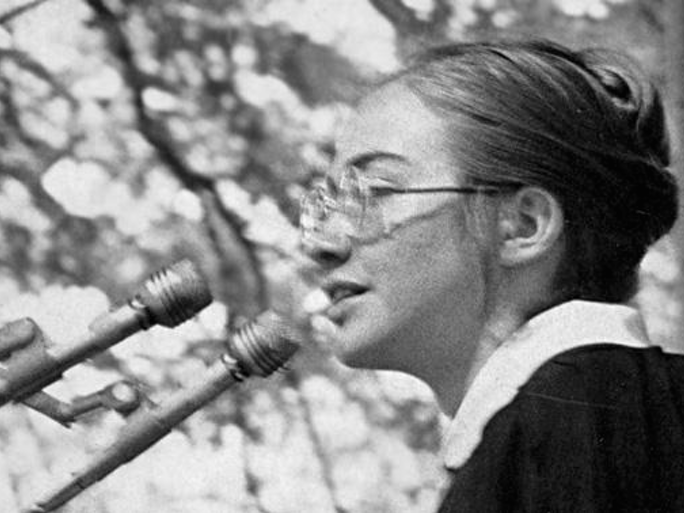

Hillary Clinton’s victory speech Tuesday night moved me far more than I expected. Since then I have been reading articles about her extraordinary journey and came across a reference she made to T. S. Eliot’s “East Coker” (from Four Quartets) in 1969 when she was a senior at Wellesley. That passage reveals something about the vision that has sustained her on her way to becoming the presumptive Democratic nominee.

Ezra Klein of Vox has an article on just how difficult the journey has been. He says that we underestimate what it has taken for a woman to break through the presidential glass ceiling:

Perhaps, in ways we still do not fully appreciate, the reason no one has ever broken the glass ceiling in American politics is because it’s really fucking hard to break. Before Clinton, no one even came close.

Whether you like Clinton or hate her — and plenty of Americans hate her — it’s time to admit that the reason Clinton was the one to break it is because Clinton is actually really good at politics.

She’s just good at politics in a way we haven’t learned to appreciate.

Klein goes on to explain how presidential campaigns favor male traits:

But the quality we adore in presidential candidates — the ability to stand up and speak loudly, confidently, and fluently on topics you may know nothing about — is gendered.

Donald Trump and Bernie Sanders are both excellent yellers, and we love them for it. Nobody likes it when Hillary Clinton yells. As my colleague Emily Crockett has written, research shows people don’t like it when women yell in general:

“Even though women are interrupted more often and talk less than men, people still think women talk more. People get annoyed by verbal tics like “vocal fry” and “upspeak” when women use them, but often don’t even notice it when men do. The same mental amplification process makes people see an assertive woman as “aggressive,” which gets in the way of women’s personal and professional advancement. Women are much more likely to be perceived as “abrasive” and get negative performance reviews as a result — which puts them in a double bind when they try to “lean in” and assertively negotiate salaries.”

Klein continues,

It may not be impossible for a woman to win the presidency the way we are used to men doing it, but it is unlikely. The way a woman is likeliest to win will defy our expectations.

Perhaps that’s why we don’t appreciate Clinton’s strengths as a candidate. She’s winning a process that evolved to showcase stereotypically male traits using a stereotypically female strategy.

Klein then lays out what that process has been:

She won the Democratic primary by spending years slowly, assiduously, building relationships with the entire Democratic Party. She relied on a more traditionally female approach to leadership: creating coalitions, finding common ground, and winning over allies. Today, 208 members of Congress have endorsed Clinton; only eight have endorsed Sanders.

This work is a grind — it’s not big speeches, it doesn’t come with wide applause, and it requires an emotional toughness most human beings can’t summon.

But Clinton is arguably better at that than anyone in American politics today. In 2000, she won a Senate seat that meant serving amidst Republicans who had destroyed her health care bill and sought to impeach her husband. And she kept her head down, found common ground, and won them over…

And Clinton isn’t just better — she’s relentless. After losing to Barack Obama, she rebuilt those relationships, campaigning hard for him in the general, serving as his secretary of state, reaching out to longtime allies who had crushed her campaign by endorsing him over her. (This, by the way, is why I don’t think you can dismiss Clinton’s victory as reflections of her husband’s success: She’s won her own elections and secured a major appointment in a subsequent administration.)

Klein concludes,

[I]n order to do something as hard as becoming the first female presidential nominee of a major political party, she had to do something extraordinarily difficult: She had to build a coalition, supported by a web of relationships, that dwarfed in both breadth and depth anything a non-incumbent had created before. It was a plan that played to her strengths, as opposed to her (entirely male) challengers’ strengths. And she did it.

Now to “East Coker.” The first stanza of Part V provided the epigraph of Clinton’s Wellesley thesis on activist Saul Alinsky, and she referenced it again in her Wellesley commencement speech. The poem is about Eliot’s frustration that language continually lets him down in the welter of emotions. “Each venture,” he writes,

Is a new beginning, a raid on the inarticulate

With shabby equipment always deteriorating

In the general mess of imprecision of feeling,

Undisciplined squads of emotion.

So how does one respond in such a case? One just keeps on trying. The effort itself is more important than whether or not one is successful. Gain and loss are “not our business”:

There is only the fight to recover what has been lost

And found and lost again and again: and now, under conditions

That seem unpropitious. But perhaps neither gain nor loss.

For us, there is only the trying. The rest is not our business.

Here’s the passage in its entirety:

So here I am, in the middle way, having had twenty years—

Twenty years largely wasted, the years of l’entre deux guerres

Trying to learn to use words, and every attempt

Is a wholly new start, and a different kind of failure

Because one has only learnt to get the better of words

For the thing one no longer has to say, or the way in which

One is no longer disposed to say it. And so each venture

Is a new beginning, a raid on the inarticulate

With shabby equipment always deteriorating

In the general mess of imprecision of feeling,

Undisciplined squads of emotion. And what there is to conquer

By strength and submission, has already been discovered

Once or twice, or several times, by men whom one cannot hope

To emulate—but there is no competition—

There is only the fight to recover what has been lost

And found and lost again and again: and now, under conditions

That seem unpropitious. But perhaps neither gain nor loss.

For us, there is only the trying. The rest is not our business.

Admittedly, the 21-year-old Clinton and the middle-aged Eliot see two different things in this passage. For Eliot, there is a sense of understandable futility (bombs were dropping on London at the time) and he is searching for hope in Christianity. The final section of “East Coker” focuses on Good Friday rather than Easter Sunday, however, meaning that he is not entirely confident in his faith. The poem ends with an image of “dark cold and empty desolation”:

Old men ought to be explorers

Here and there does not matter

We must be still and still moving

Into another intensity

For a further union, a deeper communion

Through the dark cold and empty desolation,

The wave cry, the wind cry, the vast waters

Of the petrel and the porpoise. In my end is my beginning.

By contrast Clinton, who is not an old man and who is more interested in community than in communion with God, sees “East Coker” as a call to fight the good fight, even though the outcome is uncertain. In her essay on Alinsky, which I’ve only skimmed, she is impressed with how Alinsky doesn’t allow reversals to overwhelm him. He just keeps trying.

We get a specific example of her own trying in her 1969 Wellesley speech. At one point, she is discussing how to restore lost trust between the generations, what we used to call “the generation gap” and what she refers to as “the trust bust.” She gives what I would call an Edgar Guestian “if at first you don’t succeed” reading of Eliot:

Trust. This is one word that when I asked the class at our rehearsal what it was they wanted me to say for them, everyone came up to me and said “Talk about trust, talk about the lack of trust both for us and the way we feel about others. Talk about the trust bust.” What can you say about it? What can you say about a feeling that permeates a generation and that perhaps is not even understood by those who are distrusted? All we can do is keep trying again and again and again. There’s that wonderful line in “East Coker” by Eliot about there’s only the trying, again and again and again; to win again what we’ve lost before.

.I’m not putting Clinton down when I invoke Edgar Guest. If her youthful idealism and her American can-do spirit transform Eliot’s world-weary ennui into a reminder to never give up, then more power to her. Her “trying,” as we are seeing, has taken her a very long way.