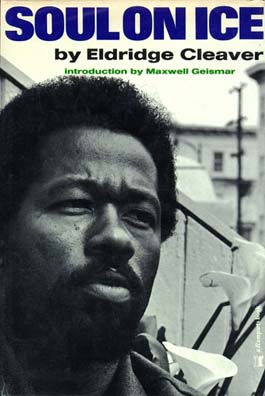

Given the uptick in racist language and increased enrollment in white supremacist groups since Barack Obama’s election, I’m going to devote one or two more posts to racism in America and then give the subject a rest for a bit. Today I want to return to my shift from southern race relations to northern when I began attending college in 1969. Call it a shift from To Kill a Mockingbird to Soul on Ice.

I get why Malcolm Gladwell, an African-Caribbean, would be infuriated by To Kill a Mockingbird. (See my past post on this.) Atticus Finch’s benevolent paternalism that tries to arrange everything—and that in the end fails to prevail against institutionalized racism—is no prescription for real change. As an 18-year-old, I was open to other ways of seeing race relations. But black militancy came as a shock.

Or at least militancy as defined by Eldridge Cleaver. I mention Cleaver’s book because it was my first encounter with one of the new conversations about race. I had determined that I needed to escape the south and all its racism, and Carleton College (in Northfield, Minnesota) seemed to fit the bill. Confirmation that I was not in Kansas anymore occurred when I encountered, in my reading for freshman orientation, Eldridge Cleaver’s Soul on Ice.

I don’t know whose idea it was to choose this book because Cleaver’s book is not one to encourage fruitful conversations about race. It is a vile book—homophobic, sexist, racist. I write about it here, not only to explain my culture shock, but also to emphasize the need for literature when we are up against such polemicists. What did I get from Cleaver’s book at this impressionable time in my life? That blacks were really, really angry at whites and that conversation was all but impossible. If Carleton’s goal was to foster real race talk and not just sloganeering, why didn’t it assign a real author like, say, James Baldwin?

The reason they didn’t, I suspect, is because at the time Baldwin had been marginalized by people like Cleaver. In the chapter titled “Notes on a Native Son,” Cleaver says that he was once enamored with Baldwin but then started to become uncomfortable with him. His discomfort crystallized when he read Another Country—which is to say, when he came fully face to face with Baldwin’s homosexuality.

Cleaver sees Baldwin’s homosexuality as a sickness, but that’s not all it is for him. In his eyes, Baldwin being less than a man also shows up in the way he is willing to talk about his debts to white writers (including Henry James) and how he refuses to see everything as black (good) and white (bad). Cleaver also doesn’t like the way Baldwin is critical of Richard Wright (Baldwin said Wright could be one dimensional in his depiction of black anger). What I see as principled desire to capture the complexity of human relationships, Cleaver sees as race self hatred and a “sycophantic” sucking up to whites:

“There is in James Baldwin’s work the most grueling, agonizing, total hatred of the blacks, particularly of himself, and the most shameful, fanatical, fawning, sycophantic love of the whites that one can find in the writings of any black Americn writer of note in our time.”

It gets even worse:

“The case of James Baldwin aside for a moment, it seems that many Negro homosexuals, acquiescing in this racial death-wish, are outraged and frustrated because in their sickness they are unable to have a baby by a white man. The cross they have to bear is that already bending over and touching their toes for the white man, the fruit of their miscegenation is not the little half-white offspring of their dreams but an increase in the unwinding of their nerves—though they redouble their efforts and intake of the white man’s sperm.”

By the way, does this image of surrendering one’s masculinity by bending over sound familiar? Here is a Rush Limbaugh quote from earlier in the year articulating white male fears of emasculation, in this case emasculation by a black man: “We are being told that we have to hope he succeeds, that we have to bend over, grab the ankles, bend over forward, backward, whichever, because his father was black, because this is the first black president.” If you want to understand the reasons for some of the rightwing acting out against Obama, think of fears articulated and fanned by statements like this.

Anyway, part of me wants to be really critical of Carleton for having assigned us an author who achieved temporary fame by taking advantage of white guilt and white self hatred (including that of Norman Mailer, whose White Negro Cleaver quotes with approval). Why were we reading a polemic instead of a work of literature, especially when our teachers seemed far too uncritical of the polemic?

But as a teacher I too have fumbled when I tried to generate meaningful conversations about race. There is no special place outside our long and painful history of race injustice for any of us to stand and be cool and objective. In 1969, how could we whites face down bullies like Cleaver when the bullies claimed to be speaking on behalf of oppression that we hadn’t done enough to combat? Some whites were so impressed that they started seeing Martin Luther King as an Uncle Tom and took Cleaver’s side against Baldwin when Baldwin called out blacks who were embracing a mindless black-white dichotomy. Many embraced Mailer’s insane prediction (as Cleaver does) that “there is a shit storm coming.”

The only shit storm that came was police violence against vocal black militants. The final confirmation that this was all delusional grandiosity was Richard Nixon sweeping to victory in 1972.

So what am I saying? In times of upheaval, look to literature for guidance, which acknowledges humans in their full complexity and refuses to reduce them to simple political prescription. Literature includes thoughtful meditations by James Baldwin and it includes humane novels like To Kill a Mockingbird. While I admit that, at times, issues must be simplified if action is to be taken, our complex reality must ultimately be reaffirmed or politics descends to demagogues and hate-filled reaction.

The most memorable thing that Cleaver ever said was that one is either a part of the problem or part of the solution. This formulation can be bracing for those who are thoughtful. After all, it gets us to ask if and how we are complicitous in existing power arrangements and what we can do to change. But too easily the statement becomes a club used against anyone who doesn’t agree with you, a simplistic polarizing that shuts out moderates and cuts off dialogue rather than encourages it. I could have used better instruction in race conversation when I was 18, I wish I had been more successful at fostering such conversation when I was a young teacher, and (as this blog indicates) I am still trying to figure out how to talk about race. It’s a long process that each generation must take up anew. Luckily we have a lot of literature that deals with race to help us along.

2 Trackbacks

[…] With less diamond-cut precision than his nonfiction writings, Baldwin succeeded at fiction that unfailingly reflected his own writhing angst, be it in the characters of his boundary-breaking gay love story Giovanni’s Room (1956) or in perhaps his most enthralling work, the heart-searing Another Country (1962). And he could meld concepts of identity — his own and the nation’s — in ways that few if any public intellectuals, civil rights leaders or politicians could, then or now. While Baldwin wrote contemporaneously with the civil rights movement and enjoyed relationships with Martin Luther King, Jr. and Bayard Rustin (who was also gay and helped engineer the 1963 March on Washington), he was never fully accepted by Christian-influenced civil rights groups. He later battled with the overtly homophobic Black Panther movement and Eldridge Cleaver, in particular, who enthusiastically emasculated him. […]

[…] critique) that it is better to be feared than to be loved. (I’ve written on that debate here.) But Cleaver himself became a caricature, and Misra can’t defend Wright beyond his time period. […]