Friday

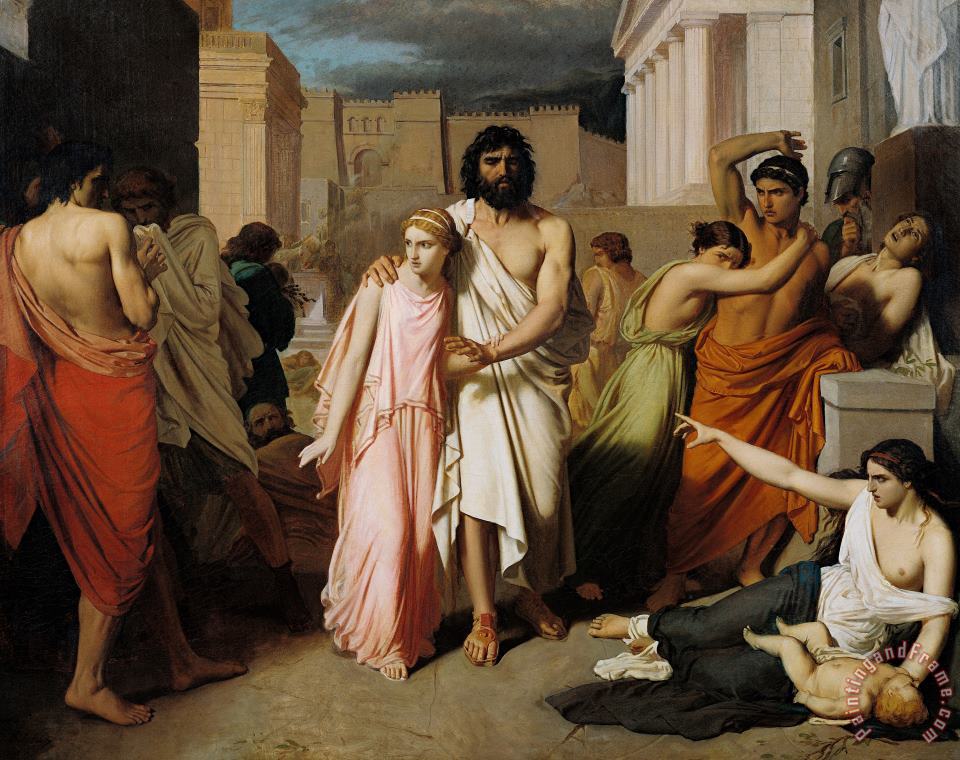

The end of American engagement in Afghanistan has an element of Greek tragedy to it. The plays of Aeschylus, Sophocles and Euripides often deal with the tension between inevitability and human choice. Just as Oedipus is going to suffer his fate regardless of what he does, it appears that the Taliban was always going to triumph in Afghanistan, regardless of what the allied forces did.

To be sure, there are points in Oedipus’s journey where he could have acted otherwise: he could have refrained from killing a man in what may be the earliest recorded case of murderous road rage (he doesn’t realize the man is his biological father). America could have refrained from attacking Afghanistan in the first place, using less dramatic measures to retaliate for 9-11. Or it could have made its point by overthrowing the Taliban government for having supported Abu Bin Laden and then withdrawn. Instead, it thought it could set up some form of democratic rule.

Likewise, if Oedipus, in his good-intentioned pride, hadn’t assumed there was something he could do about the plague, then he would never have learned about his parentage. To be sure, the plague would have continued on, given that his violations of patricide and incest taboos have caused it, but inaction would have kept the his sins hidden. It is because he believes he can handle the problem besetting his city—just as Americans thought that they could win the “war on terror” while saving Afghans from Sharia law to boot—that he gets into trouble..

Athenian audiences, knowing the story in advance, watched as Oedipus beats helplessly against a fate that is inevitable. If the play tied them into emotional knots, leading to Aristotle’s famous catharsis, it’s because of the intolerable contradiction: they simultaneously believed that something could have been done and that nothing could have been done.

So it is with our current case. Three presidents allowed an unwinnable war and an unrealizable project to go on and on, like the Theban plague, because they didn’t want to be blamed for exposing America’s helplessness, as Biden is being blamed. It certainly may be true that Biden could have handled the withdrawal better—we can debate about that—but I suspect that his critics’ major grievance is that he’s exposing them. If the foreign policy establishment doesn’t scapegoat the president, it will have to admit it screwed up royally, that the project was a fool’s errand from the get-go. Teiresias’s words to Oedipus apply equally well to them: “You have your eyesight, and you do not see.”

It’s traumatic for liberals as well. We thought that a trillion dollars and the world’s most powerful military could save women and girls from fundamentalist patriarchy and are now paying emotionally for our arrogance.

Further thought: The Washington Post’s Jennifer Rubin recently pointed to how Americans want to have reality both ways:

It is also exasperating that a new Reuters-Ipsos poll shows 61 percent of Americans want a total withdrawal from Afghanistan, but 50 percent want to send troops back in to fight the Taliban. (Even worse, 68 percent say it was going to end badly no matter when we pulled out, but 51 percent wanted to leave troops there for another year.) Logic and consistency are not voters’ strong suits.

Incidentally, I see that John Stoehr of the Editorial Page makes a similar point to my own. “Biden’s ‘mistake’ wasn’t about Afghans,” he writes. “It was about ‘allowing’ Americans to see the profound failure of America’s elites.”