Spiritual Sunday

Like many liberal Christians, I am baffled by Donald Trump’s popularity amongst rightwing evangelicals. How can anyone square the president’s behavior and his policies with Jesus’s teachings? A recent Atlantic article provides a compelling explanation: feeling embattled, the Christian right has traded core Christian principles for power.

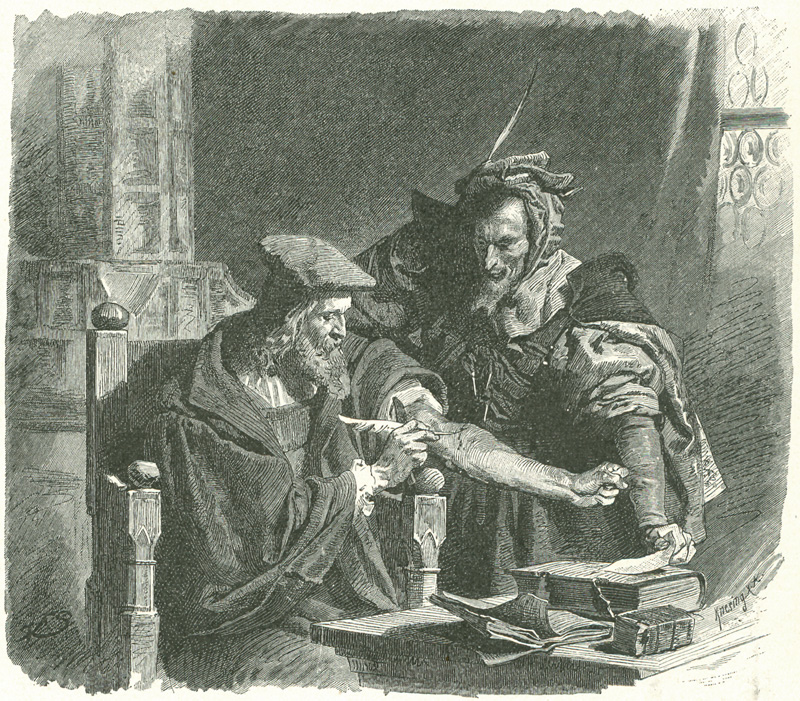

In a post written a year ago, I called this a Faustian bargain, applying Goethe’s Faust to the humanitarian crisis at the border as it was then. Things have only gotten worse in the twelve months since.

First, to assure people that not all Christians applaud Trump, my Episcopal church has put together for next year an adult Sunday school program on “Practicing Faith in a World in Need.” (I am on the committee.) Our guiding passage will be Luke 4:16-21:

He went to Nazareth, where he had been brought up, and on the Sabbath day he went into the synagogue, as was his custom. He stood up to read, and the scroll of the prophet Isaiah was handed to him. Unrolling it, he found the place where it is written:

“The Spirit of the Lord is on me,

because he has anointed me

to proclaim good news to the poor.

He has sent me to proclaim freedom for the prisoners

and recovery of sight for the blind,

to set the oppressed free,

to proclaim the year of the Lord’s favor.”

Then he rolled up the scroll, gave it back to the attendant and sat down. The eyes of everyone in the synagogue were fastened on him. He began by saying to them, “Today this scripture is fulfilled in your hearing.”

In our program, experts will expound on such topics as sex trafficking, medical outreach to poor communities, prison reform, pollution, family care, dialogue across difference, and the economics of poverty.

Jesus’s call “to set the oppressed free” would include listening seriously to asylum requests and granting them where they are warranted. (Even better would be to work seriously with the troubled countries so that people don’t need to emigrate in the first place.) An important first step is caring for these people as individuals, which was the subject of last year’s Goethe post.

From what I can tell, however, rightwing evangelicals are turning their backs on the children separated from their parents and on those packed into cages and mistreated. The Atlantic article explains that rightwing evangelicals see themselves in an existential battle for their survival and consequently are willing to embrace a man who employs cruelty to deter asylum seekers. The president unintentionally revealed that strategy this past week when he tweeted, “If Illegal Immigrants are unhappy with the conditions in the quickly built or refitted detentions centers, just tell them not to come. All problems solved!”

Author Peter Wehner points out that rightwing evangelicals feel they are involved in an existential struggle for their survival. Many

are deeply fearful of what a Trump loss would mean for America, American culture, and American Christianity. If a Democrat is elected president, they believe, it might all come crashing down around us.

And:

Many evangelical Christians are also filled with grievances and resentments because they feel they have been mocked, scorned, and dishonored by the elite culture over the years. (Some of those feelings are understandable and warranted.) For them, Trump is a man who will not only push their agenda on issues such as the courts and abortion; he will be ruthless against those they view as threats to all they know and love. For a growing number of evangelicals, Trump’s dehumanizing tactics and cruelty aren’t a bug; they are a feature. Trump “owns the libs,” and they love it. He’ll bring a Glock to a cultural knife fight, and they relish that.

In the course of his article, Wehner interviews one Karel Coppock, a conservative who, while sympathetic to rightwing evangelicals, abhors their Trump embrace. As he sees it, they have allowed their faith “to become politically weaponized”:

Coppock mentioned to me the powerful example of St. Ambrose, the bishop of Milan, who was willing to rebuke the Roman Emperor Theodosius for the latter’s role in massacring civilians as punishment for the murder of one of his generals. Ambrose refused to allow the Church to become a political prop, despite concerns that doing so might endanger him. Ambrose spoke truth to power. (Theodosius ended up seeking penance, and Ambrose went on to teach, convert, and baptize St. Augustine.) Proximity to power is fine for Christians, Coppock told me, but only so long as it does not corrupt their moral sense, only so long as they don’t allow their faith to become politically weaponized. Yet that is precisely what’s happening today.

Something similar happens to Goethe’s Faust. In his case the villain is an 18th century capitalist rather than a Trumpian xenophobe, but both have contempt for those who help needy strangers. I owe the application to a fine essay by one Kirsten Ellen Johnsen, who writes about Faust’s war on Baucus and Philemon, Greek mythological figures who represent hospitality:

In The Metamorphosis of Ovid, Baucus and Philemon are an elderly couple who live in a homely hut by a stagnant marsh. A beautiful linden tree grows nearby. When the Olympian gods Jupiter and Mercury wander on their journeys “in mortal guise,” they are refused shelter “at a thousand doors.” Finally they are welcomed by a humble old couple. Baucis and Philemon are poor, but invite the strangers in and feed them what they have available. As their wine bowl begins to replenish itself, the old couple realizes their guests are not ordinary. “Begging pardon for food so meager… they got set to kill their only goose.” To prevent this act of self-sacrifice, the gods reveal themselves. In return for their great hospitality, the hut of Baucus and Philemon is transformed into a temple in the middle of the swamp. Jupiter offers them a wish to fulfill, and they simply ask to serve the temple as long as they live, and once their time is up, they simply wish to die together. The story of Baucus and Philemon is a famous tale of the sacred honor of hospitality to strangers and the power of love. They are the original border keepers, welcoming refugees with warm hearts. Their story speaks of the gift of the stranger: the arrival of God at the door. To welcome the stranger is to tend that temple.

Baucus and Philemon, however, stand in the way of Faust’s development plans:

Faust is enraged at Baucus and Philemon’s resistance to his plans to requisition their shoreline. “That aged couple must surrender/I want their linden for my throne/The unowned timber-margin slender/Despoils me for the world I own.” His plans to drain the ocean he considers his “achievement’s fullest sweep” as a “masterpiece of sapient man. Before Faust’s will to conquer, even the bloom of the linden tree annoys him. Listening to Faust’s complaint, Mephistopheles eggs him on, “one has to tire of being just,” he cajoles him, “have you not colonized long since?” Mephistopheles is, of course, well aware of the significance of Faust’s decision to clear Baucis and Philemon from their ancient, mythic home in his closing line of the scene: “There once was Naboth’s vineyard, too.” Mephistopheles is referring to the Old Testament story of murder and betrayal of a man of God for his land by the the vilified Canaanite Priestess-Queen Jezebel. Complying with Faust’s wishes, he and his lackeys visit the old couple and set their hut ablaze.

In my previous post, I noted that a Melania Trump visit triggered Johnsen’s essay. While visiting the detention centers, the first lady wore a jacket inscribed with the words, “I don’t really care. Do U?” Care is Goethe’s major concern in his play. After Faust destroys the hut, the four gray crones of Want, Debt, Need and Care arise from “the vapors of the ashes.”

Faust can fend off the first three but he can’t dismiss Care. Care would mean, say, not deliberately abusing asylum seekers. Faust, unlike the president, acknowledges the power of caring but, like Trump, chooses not to care. Johnsen writes:

Revealing herself, [Care] demands of him, “Am I unknown to you?” Faust refuses her. “All I did was covet and attain/and crave afresh, and thus with might and gain/stormed through my life,” he preens, with the excuse that an able man may seize and “stride upon this planet’s face.” Care has given him one last chance to repent, but he has failed. “Desist! This will not work on me!/ such caterwauling I despise.” Even as he finally rejects her, he admits, “yet your power, o Care, insidiously vast/ I shall not recognize it ever.” Care then curses Faust: “Man is commonly blind throughout his life/ My Faust, be blind then as you end it.” Faust’s own proclamation is his curse: “I really don’t care, do U?”

Johnsen’s conclusion reveals what is at risk for rightwing evangelicals when they accept Trump’s treatment of the immigrants:

It is the act of hospitality that humanizes us. This is where we are leveled. The capacity for compassion, for Care, breaks open one’s heart. To destroy the Sacred Guest — the sacred act of recognizing the heart of another human being — is the ultimate mythic sacrilege, for in this betrayal lies the seed for all crimes against humanity. Care may be the only Gray Crone who might slip unnoticed into the hearts of the rich, but Goethe does not suggest that the rich might save the world through finally discovering compassion, or even worry. He is saying that the moral failure of willful, blind uncaring ultimately portends spiritual downfall.

In the Atlantic article, president of Fuller Theological Seminary Mark Labberton spells out the implications for American Christianity:

The Church is in one of its deepest moments of crisis—not because of some election result or not, but because of what has been exposed to be the poverty of the American Church in its capacity to be able to see and love and serve and engage in ways in which we simply fail to do. And that vocation is the vocation that must be recovered and must be made real in tangible action.

Labberton’s reproof does not apply to Christians like the Rev. William Barber, who heads the Poor People’s Campaign: A National Call for a Moral Revival. Those who choose resentment over love, however, have condemned themselves to Faust’s loss of soul.