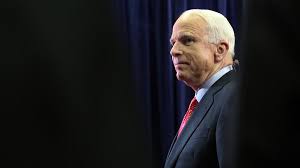

This past May, The New York Times interviewed the Sen. John McCain about his favorite books. They help account for this larger-than-life figure who passed away Saturday.

Here’s what McCain said about The Great Gatsby:

Not long ago I reread The Great Gatsby, and was impressed again by the beauty of the prose and the distinctiveness of the style. Fitzgerald told his editor he wanted to write “something new,” and he did. Nearly a century later, it still reads as something new and different though its subject, the tragedy of desiring most what Ernest Shackleton called the “veneer of outside things,” is an old one.

I suspect McCain identified with Nick, who sees the longing for something deeper within Gatsby, even though Gatsby confuses that longing with “the veneer of outside things.” McCain was better than most of his GOP colleagues at differentiating between what was important and what wasn’t. Like Nick, he saw and rejected the narcissism and moral bankruptcy of our Tom and Daisy Buchanans.

I like to think that McCain reread Gatsby because he thrilled to the final paragraphs, which spoke to his own belief in America. Nick describes the moment of transcendence experienced by the Dutch settlers as they gazed upon the new world:

And as the moon rose higher the inessential houses began to melt away until gradually I became aware of the old island here that flowered once for Dutch sailors’ eyes — a fresh, green breast of the new world. Its vanished trees, the trees that had made way for Gatsby’s house, had once pandered in whispers to the last and greatest of all human dreams; for a transitory enchanted moment man must have held his breath in the presence of this continent, compelled into an aesthetic contemplation he neither understood nor desired, face to face for the last time in history with something commensurate to his capacity for wonder.

McCain, unlike the current GOP leadership, put country above party.

I can also understand also why McCain would be drawn to Hemingway’s For Whom the Bell Tolls and would even recommend it for children. (He read it when he was 12, which is impressive.) McCain talks of the “sense of courage and adventure, and the power of [Hemingway’s] spare style,” which captures Hemingway’s existential romanticism, if I can call it that.

By this I mean that For Whom the Bell Tolls captures both the idealism of the warrior and the gritty reality of war. One doesn’t beat one’s own drum as one sacrifices oneself for a higher cause. McCain was the son and grandson of four star admirals so one sees why he would be drawn to the story of Robert Jordan doing his duty, even if it means giving up his life. He blows up the bridge that he is supposed to and then, fatally wounded, stays behind to fight off the pursuit so that his comrades can get away. McCain refused early release from captivity, insisting that he be freed only when other the other servicemen were released.

I can also see why McCain would be drawn to Huckleberry Finn, of which he says, “It’s funny and it’s scary, and it teaches us to see past our differences to the inherent dignity we possess in equal measure.” Just as Huck stands up for Jim, so McCain, more than most politicians, stood up for his principles, even vouching for his opponent of color in the presidential election. He was willing to buck his party when it went off the deep end.

Along with For Whom the Bell Tolls and Huck Finn, as a child McCain was also drawn (as was I) to boys’ adventure novels:

I read an awful lot as a boy. My father was a voracious reader, and he had a large library. My grandmother had a lot of books in her house, too. I was constantly raiding their collection for books my father had read as a child. My favorites were romantic adventures, like Ivanhoe, by Sir Walter Scott; The Romance of King Arthur and His Knights of the Round Table, by Thomas Malory; and Treasure Island and Kidnapped, by Robert Louis Stevenson. I read and reread almost everything Mark Twain wrote but principally The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn and Life on the Mississippi.

McCain was apparently a Tom Sawyer-type scamp as a young man (and like Tom, a Camelot idealist). Unlike many of us who thrilled to these books, however, he went on to have his own Treasure Island/Kidnapped type of adventure. His was far grimmer, of course, but I can imagine him, in his Hanoi prison, imagining himself as the kidnapped David Balfour or the captured Jack Hawkins, struggling to survive against impossible odds.

To my surprise, McCain also mentioned Somerset Maugham, praising his “cosmopolitan sensibility, his feel for the personal and social dramas provoked by clashing cultures.” I’ve read Of Human Bondage and The Razor’s Edge and wonder if, by cosmopolitan, he means that the dramas occur in urban rather than rural settings (for the most part). They are certainly quieter than the American works mentioned: they are not adventure stories nor novels grappling with the unending American cycle of dreaming and disillusionment (McCain mentions Faulkner as well as Fitzgerald).

Both Maugham novels grapple with the search for meaning and happiness, with Of Human Bondage’s sensitive protagonist ultimately accepting adult responsibilities and serving his community (as McCain would serve the people of Arizona after his wild military life). Perhaps McCain, with his war injuries, identifies with Philip’s club foot.

The Razor’s Edge explores “clashing cultures,” the difference between Eastern and Western sensibilities. McCain was noteworthy for his willingness to understand the perspective of people unlike himself.

The Arizona senator was far from a perfect man and, among other mistakes, bears a fair degree of responsibility for the Iraq War, one of the greatest foreign policy disasters in American history. Yet he was bigger than his faults and had more substance than any of his Republican colleagues in Congress. Some of that traces back to the fact that he was a reader.