Tom Clancy, author of Hunt for Red October, Patriot Games, and Clear and Present Danger, died Tuesday. That this hero of white male resentment passed away on the very day that extreme right wing Republicans closed down the government seems somehow significant. His body may have left us but he left his spirit behind.

Since this blog focuses on great literature, normally I would not comment on Clancy’s catchy but overly long and poorly plotted potboilers. As with Ayn Rand, however, Clancy’s popularity reminds us that power can be found in even badly written fiction. Clancy reflected and reinforced the kind of madness that we are witnessing in today’s Tea Party.

Isaac Chotiner of The New Republic notes that Clancy was so in tune with his fans that many of them did not even regard his novels as fiction. As Dan Quayle once noted, “They’re not just novels. They’re read as the real thing.”

Here’s Chotiner laying out Clancy’s political vision:

Clancy’s politics can best be described as Rambo-esque: The blame for American military defeat can best be paid at the feet of pointy-headed intellectuals and the media; America would be a better and stronger country if we would just let our tough guys take care of business; America is a great country, but government bureaucrats hold us back. The key difference was that Rambo was somewhat of a counter-cultural figure, with his long hair and alternative lifestyle. Clancy’s heroes are basically boring, straight, all-Americans. (Jack Ryan is jokingly referred to as a “boy-scout”.)

Clancy is tremendously popular where I live, which is close to the Patuxent Naval Air Force Base in southern Maryland. Years ago, before he became nationally popular, the author visited a local bookstore and there were lines around the block. Here’s Chotiner explaining why:

I recently read a quote from Clancy where he stated, “The U.S. military is us. There is no truer representation of a country than the people that it sends into the field to fight for it.” What his books argue, however, is essentially the opposite of this statement. The military and intelligence services are as superb as one could wish for, but the rest of American society has let them down.

Clancy’s novels encourage his fans to think of themselves as embattled warriors who have been let down by the rest of American society. Clancy has been so effective at establishing right wing narratives that I heard echoes of him in a recent statement by Texas Congressman John Culberson. Describing a GOP session designed to stiffen spines and keep the shutdown going, Culberson reported, “The whole room [shouted] ‘Let’s vote!’ And I said, you know like 9/11, ‘Let’s roll!'”

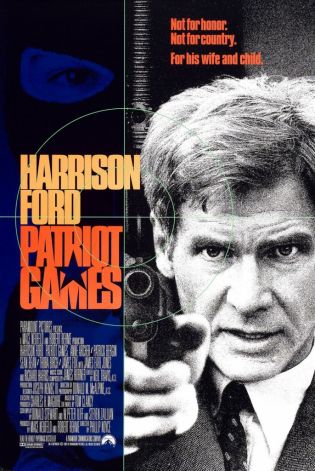

“Victory comes only to those prepared to make it, and take it,” Clancy writes in Patriot Games.

To be fair, I don’t know whether Culberson reads Clancy or not. His readiness, however, to imagine himself as one of the heroes confronting Islamic fanatics aboard United Airlines Flight 93 is the kind of fantasy that is Clancy’s stock and trade. The novels reinforce the bubble within which these Republicans live, confirming that they are fighting a grand fight against tyranny. Incidentally, we learn in Clancy’s final novel that his hero Jack Ryan is a Republican.

Fiction can work hand in hand with ideology to fire people up and push them toward extreme measures. That’s why Plato banished literature from his cerebral republic. He was worried about the passions it could inflame.

Another literary note on the shutdown – After writing the above post, I came across an even more disturbing article in The New Yorker, this one comparing John Boehner to the old Bolshevik in Arthur Koestler’s Darkness at Noon. Rubashov, although innocent, is imprisoned, interrogated, and tortured by younger colleagues.

Author George Packer uses the incident to figure out whether Boehner is likely to stand up to the House’s lunatic fringe. Packer worries that the Speaker of the House has been hollowed out by years of right wing bullying and that, as a result, he may be incapable of making one last principled stand. There is nothing to keep him from allowing Republicans and Democrats to vote together to reopen the government and raise the debt ceiling. But he may have lost all perspective, meaning that he might not do so, even if it were in his and the country’s interest. Here’s Packer quoting George Orwell’s explanation about why Rubashov caves:

Rubashov ultimately confesses because he cannot find in his own mind any reason for not doing so. Justice and objective truth have long ceased to have any meaning for him. For decades he has been simply the creature of the Party, and what the Party now demands is that he shall confess to non-existent crimes…What is there, what code, what loyalty, what notion of good and evil, for the sake of which he can defy the Party and endure further torment? He is not only alone, he is also hollow.

Applying the passage to Boehner, whom he describes as a quintessential Washington hack, and contrasting him with the last Speaker of the House responsible for a government shutdown, Packer writes,

Gingrich was a far more volatile and aggressive individual than Boehner, but the institutional norms of self-restraint, and perhaps even self-interest, have broken down under the pressure of an increasingly abnormal Republican Party. In this atmosphere, a hack can be more dangerous than a revolutionary.

If Packer is right, God help us all.

One Trackback

[…] famous, and there are multiple genres that revolve around the theme of white male victimization. (I posted recently on how the works of the late Tom Clancy revolve around this resentment..) Given that this some Tea […]