Note: If you wish to receive, via e-mail, (1) my weekly newsletter or (2) daily copies of these posts, write to me at rrbates1951@gmail.com. Comments may also be sent to this address. I promise not to share your e-mail with anyone. To unsubscribe, write here as well.

Friday

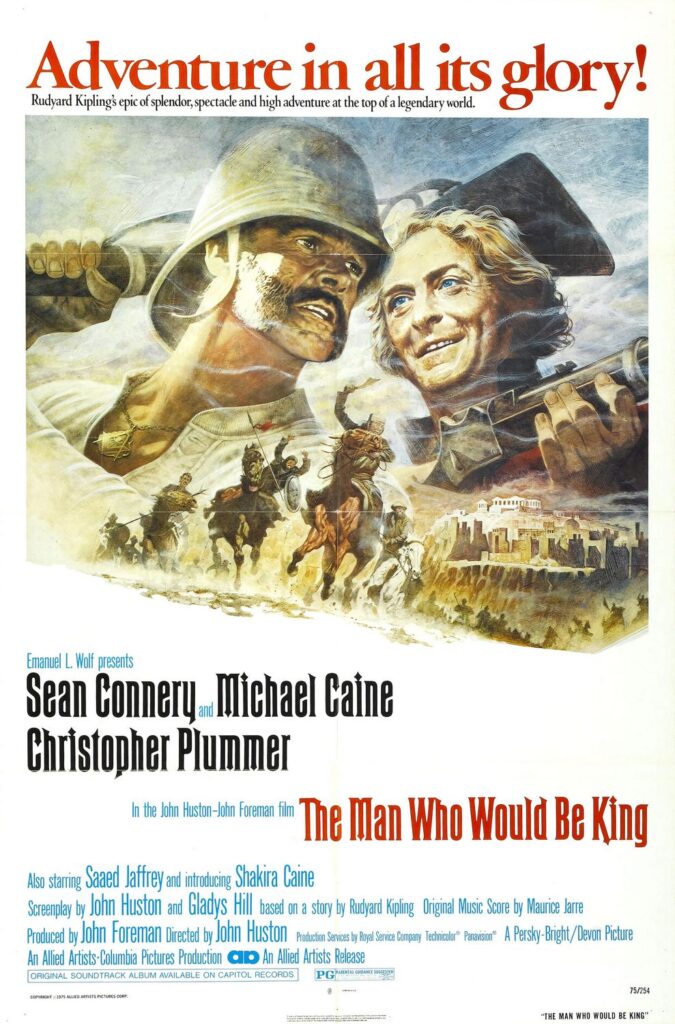

It doesn’t appear that Afghanistan, the “graveyard of empires,” will play a role in this election, perhaps because neither Republicans nor Democrats have handled it well. Nevertheless, I couldn’t help but think of our tragic experience there as I taught Rudyard Kipling’s “The Man Who Would Be King.”

I assigned the work in the post-colonial literature class that I’m currently teaching at the University of Ljubljana, and we discussed it after first looking at Kipling’s “The White Man’s Burden,” which features some of the same themes. The story carries a lesson that George W. Bush should have heeded when he first launched the American invasion. Instead of a quick in and out, as some recommended, he tried his hand at nation-building, with similar consequences.

First a note on Kipling’s poem, which frames colonialism as a selfless act on the part of Britain. In understated self-pity, the poet complains about being unappreciated by the “half-devil and half-child” natives. (In the previous class I had cited Edward Said’s complaint that Western Orientalism characterizes the East as irrational, depraved, and childlike and itself as rational, virtuous, and mature.) At one point “White Man’s Burden” compares the natives to Israelites complaining about Moses’s leadership in the desert, which positions the Brits as a legendary prophet that knows what’s best. It’s noteworthy that the poem never once mentions how much wealth the colonies generated for England. (Answer: A lot)

“The Man Who Would Be King” features two conmen who resemble—and were probably inspired by—Mark Twain’s King and Duke. (Kipling actually met with Twain when he was writing “a sequel to Tom Sawyer”). In this case, the rogues actually do go on to become kings, using cunning, superior firepower, and a fair amount of luck to sell themselves as gods, which in turn enables them to carve out a little kingdom of their own.

And if they had kept up this god masquerade, the story informs us, they would have stayed in power—just as the U.S. (or so some argue) could have swooped in, sent a message about 9-11, and left. Instead, Dravot decides he wants to create an enduring nation, complete with dynasty. In other words, he has evolved from rogue to leader. As such, he is a summation of Britain’s imperial ambitions. Here he is making his case before his skeptical partner:

“‘I won’t make a Nation,’ says he. ‘I’ll make an Empire! These men aren’t niggers; they’re English! Look at their eyes — look at their mouths. Look at the way they stand up. They sit on chairs in their own houses. They’re the Lost Tribes, or something like it, and they’ve grown to be English. I’ll take a census in the spring if the priests don’t get frightened. There must be a fair two million of ’em in these hills. The villages are full o’ little children. Two million people — two hundred and fifty thousand fighting men — and all English! They only want the rifles and a little drilling. Two hundred and fifty thousand men, ready to cut in on Russia’s right flank when she tries for India! Peachey, man,’ he says, chewing his beard in great hunks, ‘we shall be Emperors — Emperors of the Earth!

The kicker to all this is that, to form a dynasty, he needs a wife. But having a wife will mean that he will no longer be seen as a god, which is what keeps him in power. Here he is overriding his partner’s objections about finding a woman:

“‘Who’s talking o’ women?’ says Dravot. ‘I said wife — a Queen to breed a King’s son for the King. A Queen out of the strongest tribe, that’ll make them your blood-brothers, and that’ll lie by your side and tell you all the people thinks about you and their own affairs. That’s what I want.’

His planned marriage, however, blows his masquerade, and there is an uprising that ends in his death and in his partner’s crucifixion. Carnehan only barely manages to get back to the narrator to tell his story before dying of his wounds.

In America’s case, George Bush was convinced that he could sell the Afghans on democratic governance and, while some Afghans benefitted, in the end the U.S. was tone deaf to the situation on the ground. Then, in withdrawing, 183 died from a suicide blast (13 American marines, 170 Afghan civilians). For his part, Dravot is marched out on one of his rope bridges and the rope is cut:

Out he goes, looking neither right nor left, and when he was plumb in the middle of those dizzy dancing ropes, ‘Cut, you beggars,’ he shouts; and they cut, and old Dan fell, turning round and round and round, twenty thousand miles, for he took half an hour to fall till he struck the water, and I could see his body caught on a rock with the gold crown close beside.

I don’t know if the Taliban would have gained total control over the country if first the Soviet Union and then the United States hadn’t interfered in their internal affairs. As it is, many people are dead who could have been alive, and Afghanis, men as well as women, are feeling all the tyranny of fundamentalist rule. Kipling may have been an imperialist, but he also had the insight to know how super power arrogance can lead to disaster.

This is why we need our leaders reading literature.