Tuesday

My brother Sam, an enthusiastic Unitarian Universalist, gave me Karen Armstrong’s Twelve Steps to a Compassionate Life for Christmas, and I was pleased that the author sees literature playing a major role. In today’s post I share how she draws on the ancient Greeks.

Armstrong writes, “All faiths insist that compassion is the test of true spirituality and that it brings us into relation with the transcendence we call God, Brahman, Nirvana, or Duo.” Her book sets up a 12-step program for becoming more compassionate:

–Learn about compassion;

–Look at your own world;

–Compassion for yourself;

–Empathy;

–Mindfulness;

–Action;

–How little we know;

–How should we speak to one another?

–Concern for everybody;

–Knowledge;

–Recognition;

–Love your enemies.

Literature plays a major role in developing empathy. As Armstrong points out in the empathy chapter,

Imagination is crucial to the compassionate life. A uniquely human quality, it enables the artist to create entirely new worlds and give a strong semblance of reality to events that never happened and people who never existed. Compassion and the abandonment of ego are both essential to art…Art calls us to recognize our pain and aspirations and to open our minds to others. Art helps us—as it helped the Greeks—to realize that we are not alone; everybody else is suffering too.

Armstrong references the Greeks because her observation arises out her discussions of Aeschylus’s Oresteia trilogy, Euripides’s Medea and Heracles, and Sophocles’s Oedipus and Oedipus at Colonus

The Greek dramatists, she says,

were trying to sensitize their audience to pain. Instead of maintaining ourselves in a state of deliberate heartlessness in order to keep suffering at bay, we should open our hearts to the grief of others as though it were our own.

Armstrong says that the plays were

both a spiritual exercise and a civic meditation, which put suffering onstage and compelled the audience to empathize with men and women struggling with impossible decisions and facing up to the disastrous consequences of their actions. The Greeks came to the plays in order to weep together, convinced that the sharing of grief strengthened the bond of citizenship and reminded each member of the audience that he was not alone in his personal sorrow.

Consider the conclusion of Euripides’s Heracles, for instance, in which we watch Heracles realize he has killed his wife and children in a fit of divinely inspired madness:

Theseus, legendary king of Athens, embraces the broken man and leads him gently offstage, the two bound together “in a yoke of friendship.” As they bid him farewell, the chorus laments Heracles’s fate “with mourning and with many tears…For we today have lost our noblest friend.” The art of the dramatist enabled the audience to achieve an expansion of sympathy, so that they had a taste of the immeasurable power of compassion. An audience that could befriend a man who had committed an act like that of Heracles had achieved a Dionysian ekstasis, a “stepping out” of ingrained preconceptions in an empathy that, before seeing the play, they would probably have deemed impossible.

Audiences experience similar compassion from watching Oedipus at Colonus, where a man who has committed

unspeakable but unintentional crimes becomes a source of blessing to the citizens of Athens when they have the compassion to take him in and give him asylum.

Similarly, at the conclusion of Aeschylus’s Oresteia trilogy, spectators learn that Orestes can be pardoned for killing his mother, even though the furies that have pursued him must still be honored. Athena placates them by

offering them a shrine in the city, decreeing that henceforth they will be known as the Eumenides, “the Compassionate Ones.”

Armstrong observes that the transformation occurs only when we acknowledge our dark urges and take responsibility for them (as Athena does). Once we do so, we can “transform these primitive passions into a force for compassion.”

In other literary citations, Armstrong quotes Wordsworth in the action chapter, drawing on The Prelude and Tintern Abbey to emphasize how even “one small act of kindness can turn a life around.” After describing one such act from a dying nun when she was a troubled novice, Armstrong writes,

The British poet William Wordsworth wrote of iconic moments like this, which become a resource for us over the years:

There are in our existence spots of time,

That with distinct pre-eminence retain

A renovating virtue, whence–depressed

By false opinion and contentious thought,

Or aught of heavier or more deadly weight,

In trivial occupations, and the round

Of ordinary intercourse–our minds

Are nourished and invisibly repaired…

My point is that we can all create “spots of time” for others, and that many of these will be the “little, nameless, unremembered, acts of kindness and of love” that, Wordsworth claimed in another poem, form “that best portion of a good man’s life.”

Some of the best examples of unexpected compassion occur in Armstrong’s “Love Your Enemies” chapter. For example, although the Persians pillaged, burned and trashed Athens eight years earlier, in The Persians Aeschylus

asks the audience to weep for the Persians and asks them to see Salamis from the enemy’s point of view. Xerxes, the defeated Persian general, his mother, Atoss, and the ghost of the late Persian king Darius are all treated with sympathy and respect. All speak of the piercing sorrow of bereavement, which has stripped away the veneer of security to reveal the terror that lies at the heart of human life….[T]here is no triumphalism and no gloating, and Persia are described as “sisters of one race…flawless in beauty and grace.”

Armstrong explains Aeschylus believes that Athens too is becoming guilty of pride and greed as it begins to violate the Delian League, which had come together to oppose Persia. Compassion for another leads to vital self examination.

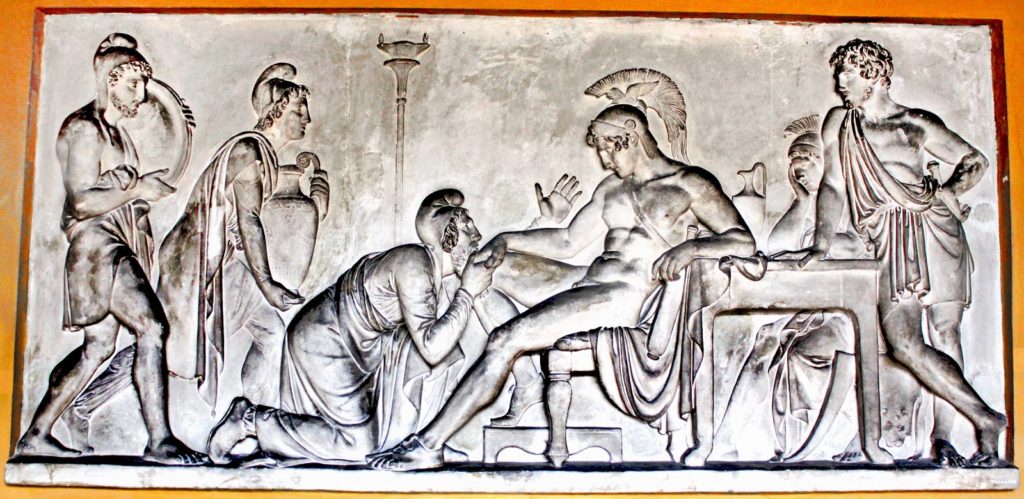

An even more remarkable instance of compassion occurs in The Iliad. After Achilles has killed Hector and desecrated his body for killing his best friend, he encounters Hector’s grieving father:

But one night, King Priam of Troy enters the Greek camp incognito and makes his way to Achilles’s tent to beg for the body of his son. To the astonishment of Achilles’s companions, the old man throws off his disguise and falls at the feet of his son’s slayer, weeping and kissing the hands that were “dangerous and man-slaughtering and had killed so many of his sons.” His utter abasement awakens in Achilles a profound grief for his own dead father, and he begins to weep too, “now for his own father, now again for Patroclus.” The two men cling together, mourning their dead. Then Achilles rises, takes Priam’s hand, and raises him gently to his feet “in pity for the grey head and the grey beard. Carefully, tenderly, he hands over Hector’s body, concerned that its weight might be too much for the frail old man. And then the two enemies look at each other in silent awe:

Priam, son of Dardanos, gazed upon Achilles, wondering

At his size and beauty, for he seemed like an outright vision

Of gods. Achilles in turn gazed on Dardanian Priam

And wondered, as he saw his brave looks, and listened to him talking.

Armstrong’s conclusion sums up her book:

In the midst of a deadly war, the shared suffering and pity of it all had enabled each man to transcend his hatred and see the sacred mystery of his enemy.

In her epilogue, Armstrong acknowledges that the embrace does not end the Trojan War. Becoming a compassionate person and having that compassion impact others is a lifelong process. Nevertheless, she shows compassion to be worth striving for, a way to approach divinity.