Thursday

Last week the Washington Post’s editorial page editor wrote a Better Living through Beowulf-type column about War and Peace. Tolstoy’s novel, Fred Hiatt says, gives us a way of understanding Donald Trump and what it will take to defeat him.

First he quotes the following passage and asks who it reminds us of:

“A man of no convictions, no habits, no traditions. . . . The incompetence of his colleagues, the weakness and insignificance of his opponents, the frankness of the deception, and the dazzling and self-confident limitation of the man raise him to the head . . . and without attaching himself to any one of them, advances to a prominent position,” Tolstoy writes.

Eerie, right? The dazzling and self-confident limitation of the man.

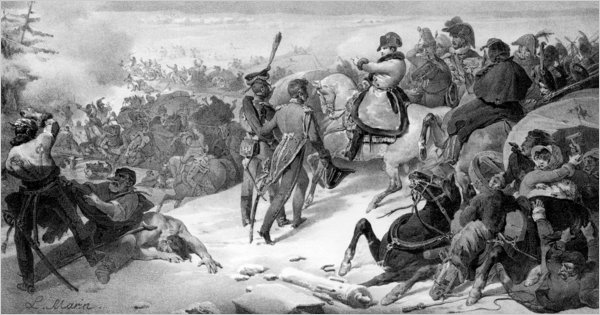

Okay, I dropped a couple of words from the passage. Tolstoy actually wrote “the seething parties of France,” and “the head of the army.” He was in fact describing not our president but Napoleon, for whom the Russian author harbored a magnificent contempt.

If Trump is Napoleon, then what can we learn from Napoleon’s defeat? Hiatt points out that, according to Tolstoy, the acts of great men are far less consequential than “the separate decisions of thousands of individuals: soldiers, peasants, shopkeepers, lords,” whose “actions flow together into a force that czars and generals can only pretend to control.”

Hiatt sees Trump, like Napoleon, as a clear and present danger to the nation–in our case, to our identity as a country “that welcomes newcomers and outsiders and allows them, in their turn, to become American.” Without this dimension, we are no longer an exceptional nation. While acknowledging that some of the battles must be fought in the courts and in Congress, Hiatt, like Tolstoy, says that our fate ultimately lies in the hands of we the people:

[T]he essential battle for the nation’s soul will be fought by every one of us, every day.

It is a battle we will win by embracing each other’s humanity: by welcoming the mosque down the street, helping a “dreamer” stay in school, translating a form for the parent at the next desk at back-to-school night. It is a battle, as Tolstoy would have understood, that will be won or lost by the nation’s soldiers, farmers and shopkeepers, and by its nurses and factory workers and teachers and office workers, too; by each of us, day by day, encounter by encounter.

Hiatt concludes with one caveat, however. Tolstoy, he writes,

wasn’t totally right about history. Even the mountebanks, the leaders of no convictions, can shift the course of events. But the rest of us, impelled by the generosity that has made America a great country, may have more power than we think.

This isn’t a real disagreement. After all, Trump, like Napoleon, can do a lot of damage before he is driven out. I only pray that Hiatt is right that we will be saved by our better angels.

Other applications of War and Peace

Trump, Prince Vasili, and Pure Cynicism

Great Pro-War Lit Doesn’t Exist

Tolstoy Calls Us To Aid Syrian Refugees

Tolstoy and the Forerunners of Twitter

On Sickness and the Power of Prayer

Hillary before Judges Like Tolstoy’s Pierre

Tolstoy and Climate Change Denial

Panicked by Trump? Turn to Lit