Spiritual Sunday

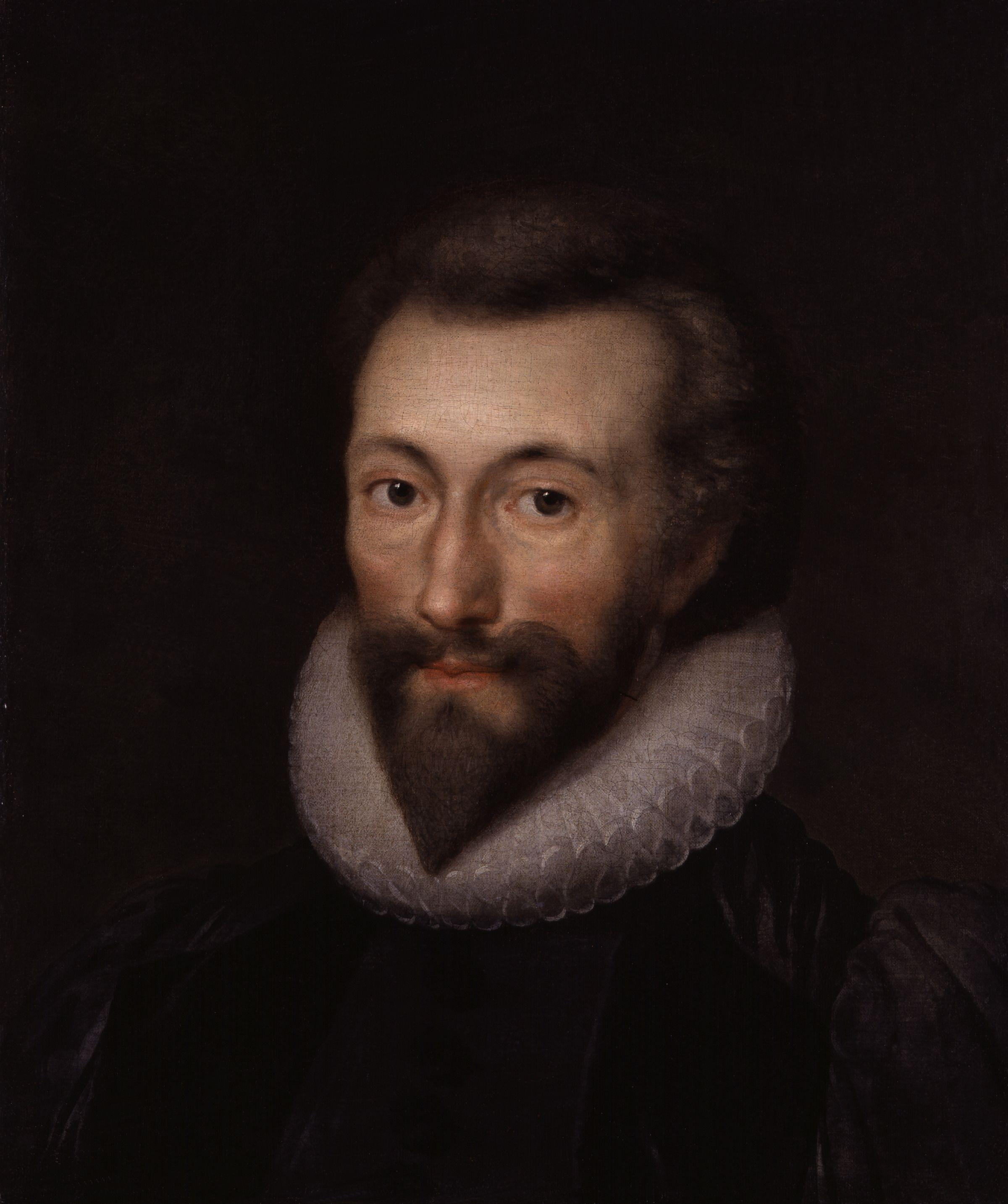

Today’s post is about how one of my students, an African American woman with a difficult childhood, found John Donne to be a kindred spirit. In the 17th century metaphysical poet she recognized her own religious struggling.

Delia (not her real name) has given me permission to tell her story. Her father left her family when she was young and her mother spent seven years in jail. Delia was raised by her grandparents, who brought her up in their Christian faith. After Delia’s mother was released, the family lived in a halfway house, and Delia was disappointed when the restored family didn’t live up to her dreams. Her sister ran away after a failed suicide attempt, and Delia also mentions neurosurgery and the death of a beloved pet. As a result, she found herself doubting God.

Her grandfather had told her many times “that I was blessed, that God has a plan for me, and that I’m here for a reason.” But he also indicated that only those who fully opened their hearts to God would go to heaven, leading to deep anxieties when Delia found herself plagued by doubts. The doubts began when, as a child, a cousin committed suicide and Delia’s grandfather couldn’t confidently tell Delia that the cousin was with God. The doubts grew when Delia became an adolescent and she found herself seriously worried that she was bound for hell:

As the years went on, I found it harder to believe the words that once gave me strength and courage to face life’s challenges. My demons multiplied daily and soon my light dimmed. By the age of twelve, I started questioning if my existence was truly necessary, and at the age of fourteen, suicidal thoughts plagued me every night. My anxieties, depression, fears, and faith did battle into the night as I curled up in my bed and cried myself to sleep.

By the time Delia reached college, she had come to believe that “God does not have a plan for me” and that “my life will always have meaningless suffering.” Even when she thought back to her childhood training and told herself that “that none of that was true,” she still “could not stop myself from thinking these negative, deadly thoughts.”

To sum up her situation, she couldn’t reconnect with her easy childhood faith and saw her doubts as evidence that she was pushing God away, thereby bringing down upon her head terrible consequences. To make matters worse, she blamed herself for complaining. That’s because she had been taught a version of Christianity that contained a (non-scriptural) strain of self-reliance:

Since childhood I had been taught that God only helps those that help themselves, those that do not expect God to do it all for them. I tried every day to do just that: stand on my own two feet and not complain.

In Donne’s Sonnets #5 and #9, Delia sees a man caught in a version of her own mind trap. Donne, like Delia, knows that God is merciful to those who surrender to Him, and, like Delia, he perceives his doubts getting in the way, thereby triggering God’s wrath. In Sonnet 9, he believes his treacherous mind is taking him to hell whereas mindless objects like poisonous minerals, the sin-inducing apple, lecherous goats, and envious serpents get a pass:

If poisonous minerals, and if that tree,

Whose fruit threw death on (else immortal) us,

If lecherous goats, if serpents envious

Cannot be damn’d, alas ! why should I be?

Why should intent or reason, born in me,

Make sins, else equal, in me more heinous?

And, mercy being easy, and glorious

To God, in His stern wrath why threatens He?

Donne concludes that he can’t fix himself and that God must intervene. Donne asks God to step in and take over, forgetting and helping Donne to forget his lack of faith:

But who am I, that dare dispute with Thee ?

O God, O ! of Thine only worthy blood,

And my tears, make a heavenly Lethean flood,

And drown in it my sin’s black memory.

That Thou remember them, some claim as debt ;

I think it mercy if Thou wilt forget.

Delia finds a mind trap also operating in Sonnet 5. It opens as follows:

I am a little world made cunningly

Of elements, and an angelic sprite ;

But black sin hath betray’d to endless night

My world’s both parts, and, O, both parts must die.

Delia observes,

If one were to survey the world, one would find that these fears and anxieties are universal. Though John Donne’s internal battle for his eternal soul is not a unique endeavor, it is a grueling one nonetheless. The salvation of the soul is one of the hardest puzzles man will ever have to figure out but it all comes down to the mind. Through his sonnets, Donne’s struggle for dominance with his mind seems to be ongoing throughout his life, one that he tends to lose more often than not. The mind can be a powerful instrument and a useful ally, but it can also be the greatest enemy that any man will ever face.

Delia is somewhat consoled by how, at the end of both poems, Donne acknowledges that

despite his vast amount of knowledge, he knows absolutely nothing of God’s plans or thinking…At the end of Sonnet 9, he asks, “But who am I that dare dispute with thee O God?” as he admits [his ignorance]. In Sonnet 5 he asks that God “burn me…with a fiery zeal/Of thee and thy house, which doth in eating heal.” He is admitting to both himself and God that he cannot find the power within himself to save himself, that he needs God’s helping hand to open his heart.

In other words, she is beginning to realize that she has divine assistance. She doesn’t have to entirely stand on her own two feet.

Delia concludes,

Much like John Donne, I was at war with my mind and how I perceived God, my life, and myself. No matter how hard I tried, nothing ever seemed to be good enough. Reading Donne’s poems felt much like looking in a mirror. The fears and anxieties that John Donne struggles with are universal, especially within the religious communities. Even so, Donne’s true battle is not with his faith but with himself.

Our students are often engaged in titanic spiritual struggles. When needed, our greatest poets step up to the plate.

Further thought: On Thursday I wrote about Yale English majors who were complaining about being required to take surveys of dead white male authors. I call Delia to testify for the defense.