Wednesday

In recent weeks the two GOP leaders, Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell and Speaker of the House Paul Ryan, have come under criticism for their continued support of a candidate who stokes racial, ethnic, and gender resentment by saying one outrageous thing after another. Unfortunately, rather than taking principled stands, they have been behaving like the politician Sir Timothy Beeswax in Anthony Trollope’s Palliser novels.

Before turning to Trollope’s Beeswax, let’s look at our own malleable-as-beeswax politicians. Although Ryan accused Donald Trump of “textbook racism” for attacking a Latino judge who will be ruling on suits against Trump “University,” he still said that Trump’s policy positions trump any other considerations:

“I disavow these comments — I regret those comments that he made,” Mr. Ryan said. “I think that should be absolutely disavowed. It’s absolutely unacceptable. But do I believe that Hillary Clinton is the answer? No, I do not.”

“I believe that we have more common ground on the policy issues of the day and we have more likelihood of getting our policies enacted with him than with her.”

McConnell has taken a similar stand and I focus on him because he is particularly Beeswaxian. First, note how the ends justify the means in McConnell’s Republican National Convention speech, as reported by the Washington Post:

McConnell’s argument here has become a familiar one: Trump is a Republican, so let’s vote for him. It’s an extension of what skeptical-yet-out-of-options Republicans have been saying since Trump clinched the nomination in May: He’s not what we wanted, but he’s better than Hillary Clinton.

This is nothing new for McConnell. It has long been clear that he only cares about his party winning and himself presiding over the Senate. Early in 2008, before the president had even been sworn in, he devised an all-out obstructionist strategy where Obama would be checked in everything he attempted, including measures previously proposed by Republicans:

Before the health care fight, before the economic stimulus package, before President Obama even took office, Senator Mitch McConnell, the Republican minority leader, had a strategy for his party: use his extensive knowledge of Senate procedure to slow things down, take advantage of the difficulties Democrats would have in governing and deny Democrats any Republican support on big legislation.

As a result, the last three Congresses have been the least productive in the history of the United States, and it appears that nothing will change for the remainder of President Obama’s term. Just last week McConnell boasted of having subverted the president’s constitutional prerogative to appoint Supreme Court justices:

One of my proudest moments was when I looked at Barack Obama in the eye and I said, “Mr. President, you will not fill this Supreme Court vacancy.”

Sir Timothy Beeswax shows up in Prime Minister but he is described most thoroughly in The Duke’s Children (1879). A member of the Conservatives, his goal has always been to be “the first man in the House of Commons.” The well-being of his country is secondary:

This plan [being the first man] he had all but gained,—and it must be acknowledged that he had been moved by a grand and manly ambition. But there were drawbacks to the utility and beauty of Sir Timothy’s character as a statesman. He had no idea as to the necessity or non-necessity of any measure whatever in reference to the well-being of the country. It may, indeed, be said that all such ideas were to him absurd, and the fact that they should be held by his friends and supporters was an inconvenience.

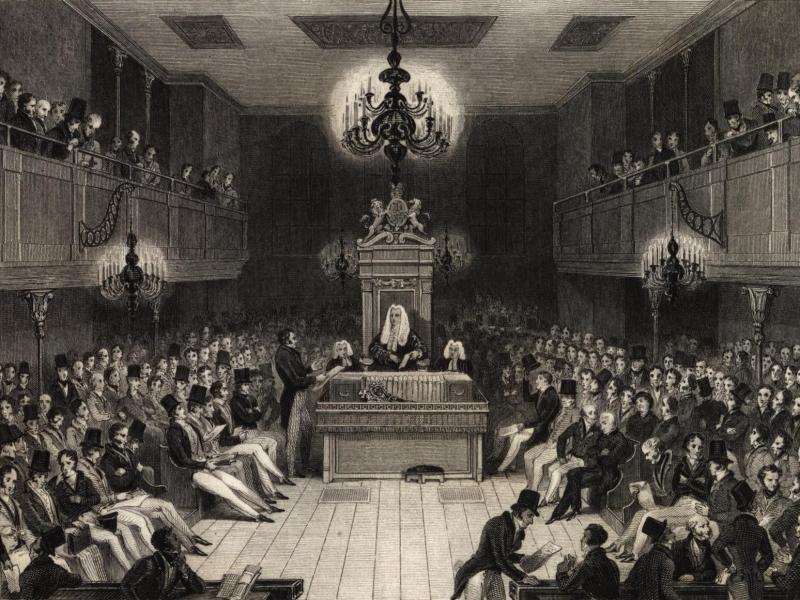

Beeswax loves Parliament because that institution, more than any other, serves his ambition of becoming “the cream of the cream.” Only as “chief of the strongest party” does Sir Timothy get to bestow favors and snub rivals:

Parliament was a club so eligible in its nature that all Englishmen wished to belong to it. They who succeeded were acknowledged to be the cream of the land. They who dominated in it were the cream of the cream. Those two who were elected to be the chiefs of the two parties had more of cream in their composition than any others. But he who could be the chief of the strongest party, and who therefore, in accordance with the prevailing arrangements of the country, should have the power of making dukes, and bestowing garters and appointing bishops, he who by attaining the first seat should achieve the right of snubbing all before him, whether friends or foes, he, according to the feelings of Sir Timothy, would have gained an Elysium of creaminess not to be found in any other position on the earth’s surface. No man was more warmly attached to parliamentary government than Sir Timothy Beeswax; but I do not think that he ever cared much for legislation.

Beeswax and McConnell are alike in that their thorough understanding of their institution makes them appear as conjurers:

[Beeswax] had studied the ways of Members. Parliamentary practice had become familiar to him. He had shown himself to be ready at all hours to fight the battle of the party he had joined. And no man knew so well as did Sir Timothy how to elevate a simple legislative attempt into a good faction fight. He had so mastered his tricks of conjuring that no one could get to the bottom of them, and had assumed a look of preternatural gravity which made many young Members think that Sir Timothy was born to be a king of men.

In our cynical age, we may think that all politicians are Mitch McConnells, but I do not think this is actually the case. In any event, it’s worth reminding ourselves of the ideal towards which politicians should aspire, which is voiced by the Duke of Omnium in a letter to his son when the latter is elected to Parliament. The Duke, a Liberal, was once Prime Minister and is the quintessential example of a principled politician. He writes,

I would have you always remember the purport for which there is a Parliament elected in this happy and free country. It is not that some men may shine there, that some may acquire power, or that all may plume themselves on being the elect of the nation. It often appears to me that some members of Parliament so regard their success in life,—as the fellows of our colleges do too often, thinking that their fellowships were awarded for their comfort and not for the furtherance of any object as education or religion. I have known gentlemen who have felt that in becoming members of Parliament they had achieved an object for themselves instead of thinking that they had put themselves in the way of achieving something for others. A member of Parliament should feel himself to be the servant of his country,—and like every other servant, he should serve. If this be distasteful to a man he need not go into Parliament. If the harness gall him he need not wear it. But if he takes the trappings, then he should draw the coach. You are there as the guardian of your fellow-countrymen,—that they may be safe, that they may be prosperous, that they may be well governed and lightly burdened,—above all that they may be free. If you cannot feel this to be your duty, you should not be there at all.

It shouldn’t take the prospect of electing an unstable demagogue to remind our elected leaders that service to country is foremost. In past crises, American politicians have demonstrated that they could rise above party concerns, and Republican Senator Susan Collins has just declared that she will not be voting for Donald Trump. Will other Republicans, including McConnell and Ryan, follow suit?