Spiritual Sunday

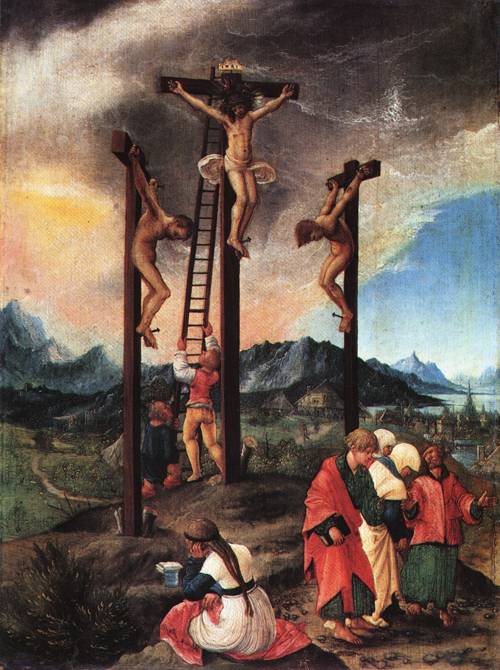

For reasons that some of my readers will know (and I hope will inform me), today’s New Testament reading involves the crucifixion, even though we are half a year from Easter. It features the story of the two thieves.

Perhaps it’s included now to make the point that salvation is spiritual rather than earthly. That seems to have been the theme in recent readings, including last week’s about the true temple being built of God’s love, not “beautiful stones” (see my post on the George Herbert poem about the passage). In any event, it gives me an excuse to share two fine poems.

Here’s the passage:

When they came to the place that is called The Skull, they crucified Jesus there with the criminals, one on his right and one on his left. Then Jesus said, “Father, forgive them; for they do not know what they are doing.” And they cast lots to divide his clothing. The people stood by, watching Jesus on the cross; but the leaders scoffed at him, saying, “He saved others; let him save himself if he is the Messiah of God, his chosen one!” The soldiers also mocked him, coming up and offering him sour wine, and saying, “If you are the King of the Jews, save yourself!” There was also an inscription over him, “This is the King of the Jews.”

One of the criminals who were hanged there kept deriding him and saying, “Are you not the Messiah? Save yourself and us!” But the other rebuked him, saying, “Do you not fear God, since you are under the same sentence of condemnation? And we indeed have been condemned justly, for we are getting what we deserve for our deeds, but this man has done nothing wrong.” Then he said, “Jesus, remember me when you come into your kingdom.” He replied, “Truly I tell you, today you will be with me in Paradise.” (Luke 23:33-43)

Both poems focus on “the bad thief.” Harriet Monroe’s “The Thief on the Cross” (1905) ends with an intriguing question. Imagining that the bad thief goes to hell rather than heaven, she wonders how the conversation during Jesus’s descent into hell would have gone. She leaves the answer open::

Three crosses rose on Calvary against the iron sky,

Each with its living burden, each with its human cry.

And all the ages watched there, and there were you and I.

One bore the God incarnate, reviled by man's disdain,

Who through the woe he suffered for our eternal gain

With joy of infinite loving assuaged his infinite pain.

On one the thief repentant conquered his cruel doom,

Who called at last on Christ and saw his glory through the gloom.

For him after the torment souls of the blest made room.

And one the unrepentant bore, who his harsh fate defied.

To him, the child of darkness, all mercy was denied;

Nailed by his brothers on the cross, he cursed his God and died.

Ah, Christ, who met in Paradise him who had eyes to see,

Didst thou not greet the other in hell's black agony ?

And if he knew thy face, Lord, what did he say to thee?

As I read heaven and hell, they are states we undergo when we are still alive. The one thief dies in a hellish state, the other gets a glimpse of “infinite loving.” He sees Christ’s “glory through the gloom.”

Put another way, in the two thieves we see two different ways of living and dying. The “child of darkness” sees nothing but “hell’s black agony” while the “thief repentant conquer[s] his cruel doom.” We can spend our last hours desperately clutching life or we can open ourselves to a deeper vision.

John O’Donnell’s more recent poem points out that we all have more than a little of “The Bad Thief” in us. “Admit it: you’d have done the same,” he tells us.

In other words, the line between the “one redeemed” and the “one condemned” is very thin. We all waver between our belief in love and our panic over mortality. Only a scribbling “hack” makes the choice sound easy.

We’d had to wait while someone went for nails.

The soldiers stood around us, eating dates.

I’d seen him once before, and heard the stories,

though how on earth he’d ended up like this,

with the two of us for company, I don’t know.

A wind that smelt of hyssop-leaves. When I offered him

my hand one big bruiser clanked his sword.

“Word is,” I whispered, “you could save us all.

Well, now’s your chance!” Admit it: you’d have done

the same. But he just sighed: “Too late for me,

though not for you.” His pale hand small in mine

as they came towards us with the hammer. One

redeemed, and one condemned, some hack scribbled later.

But what was there between us in the end?

As I read “Bad Thief,” the compassionate line that ends “The Coward,” Eve Merriam’s poem about a deserter, comes to mind: “Coward, take my coward’s hand.” This in turn provides the answer to Monroe’s concluding question: Jesus greets us in our agony and extends to us his infinite compassion.