Monday

Adam Gallinsky, who teaches “leadership and ethics” at Columbia Business School, has written an eye-opening Washington Post article on the role of “anticipated regret” in vaccination decisions. Understanding the psychology at work, he says, “can help us get more shots into arms, removing one of the final obstacles to controlling the virus.” As I thought about the fear of feeling regret, I looked for literary examples and settled on, of all things, Wuthering Heights. I realize this is a stretch but hear me out.

First, however, to Gallinsky, who contends that positive incentives don’t necessarily work with the vaccine hesitant. That’s because, in their cost-benefit calculations, they fear the regret that comes with doing something wrong more than they fear the regret that might arise from doing nothing at all. To illustrate, Gallinsky cites the work of a Nobel-winning economist:

Daniel Kahneman, who won a Nobel Prize in economics for his work on decision-making — have demonstrated these tendencies in a series of experiments. For example, Kahneman found that people anticipate feeling more regret if they were to lose money by switching to a new stock vs. taking a loss on their current stock. And this regret is maximally intensified when we freely choose to take action— we are not ordered or coerced — and when it involves new or experimental activities. For example, Kahneman found that people anticipate more regret when imagining an accident that occurs while driving home along a new route compared with driving on one’s normal route. Anticipated regret is why people often prefer to stand still rather than move forward.

Gallinsky says that calculations often change, however, with vaccine mandates, which are proving to be overwhelmingly effective. (Gallinsky points out that, despite fierce initial resistance among New York police and predictions of mass resignations, in the end no more the three dozen out of 35,000 officers refused to get the shot.) “When people don’t feel the weight of making their own choice,” Gallinsky points out, “they aren’t as tormented by the anticipated negative outcomes of their decision.”

Gallinsky adds that mandates should be accompanied by “empathic firmness.” “When people sense that those enforcing a policy are listening to them,” he says, “they are less likely to shut down.”

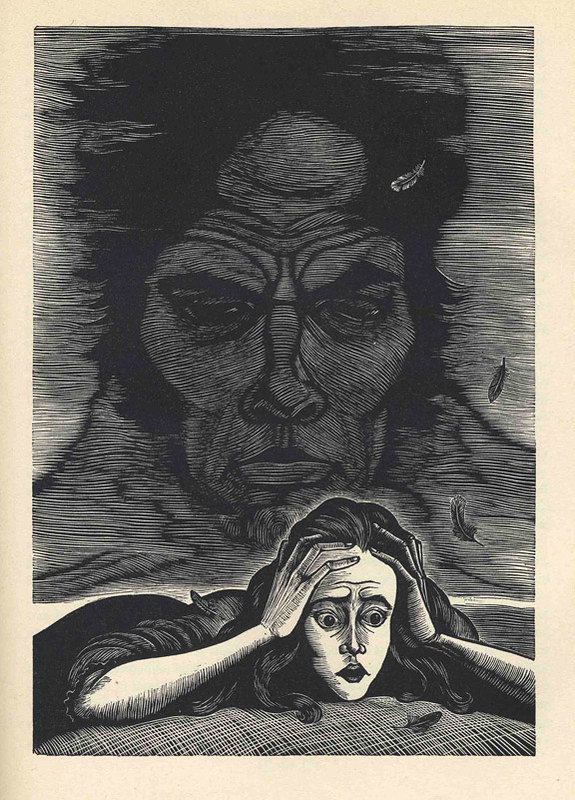

Now to literature, where one finds many characters who take a seemingly safe and familiar route rather than an adventurous one (not that getting vaccinated is all that adventurous), only to regret it later. I single out Emily Bronte’s headstrong Catherine Earnshaw, who marries another member of the gentry rather than her soulmate Heathcliff. Anticipating regret if she makes the wild and unconventional choice, she chooses instead the familiar one, only to find herself deeply unhappy. Because she is a strong personality, she makes everyone around her miserable as well, and the household is in constant turmoil until she dies.

I realize now, in applying the work, that I disagree slightly with Gallinsky. He makes it sound as though it is only because the vaccine is unfamiliar that some are unwilling to take it. He doesn’t mention the positive rewards that come with not taking it. In Catherine’s case, the reward is a comfortable and familiar upper-class life. In the case of vaccine resisters, the reward is getting to feel both superior too and victimized by the Enlightenment world of science and medical expertise. One gets to rail against liberal elites and imagine them as frauds. In other words, many vaccine hesitaters anticipate regret at leaving a closed ecosystem that they have committed themselves to. Leaving would be more emotionally charged than selling stock or taking a different route home.

Sacrificing that ecosystem for mere health seems a poor tradeoff, even when health is no further away than the nearest pharmacy.

It appears a poor tradeoff, anyway, until one is hospitalized with Covid, at which point the medical profession appears far more attractive. Many find themselves experiencing actual regret at this stage, as Catherine does with her marriage. Unfortunately, by this point it’s too late.

Interestingly, like a number of the vaccine resisters, Catherine tries to have it both ways: she wants to have her husband and her lover at the same time. (Linton and Heathcliff, understandably, are less enthused by the idea.) For their part, the anti-vaccine crowd want to rail against doctors until they want these same doctors to cure them, just as they want the “socialist” programs of Medicare and Obamacare to cover their medical bills. For that matter, they don’t acknowledge how vaccines have saved us from small pox, polio, the measles, chicken pox, mumps, etc, etc. Like Catherine, many behave like entitled children as they fail to take responsibility for supporting the institutions that support them.

Commentator Tom Nichols, who describes himself as a Never Trump conservative, plays the role of the no-nonsense Nelly Dean, housekeeper at Wuthering Heights who is impatient with Catherine’s histrionic fits, when he calls America “an unserious nation threatened by millions of spoiled, stupid adult children.” Real adults act responsibly–which in this case means taking steps to protect themselves and others. The gyrations of anticipated regret look awfully silly when a safe and effective vaccine is ready to hand.