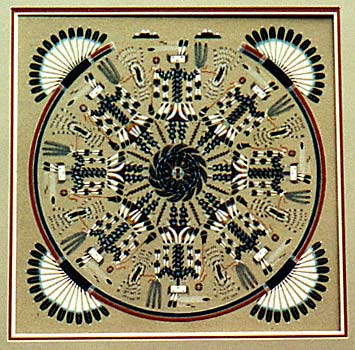

Navajo sand painting

It may have seem incongruous, in a website featuring old works, to have started off my first blog entry with a quotation from the contemporary Laguna Pueblo author Leslie Marmon Silko. But I find her faith that stories have the power to “fight off sickness and death” so close to my own view that it seemed appropriate. I will take a break from writing about Beowulf to discuss how Silko explores this idea in her remarkable novel Ceremony.

In one respect, Silko is talking about a very specific threat, which is the death of the cultural identity of the Laguna Pueblo. The stories that they have handed down have helped them maintain a sense of themselves within a larger culture that has threatened to overwhelm them with its own stories, most notably such stories as the march of western civilization, the benefits of technological progress, manifest destiny, the American dream, and so forth. And there are negative stories as well, most notably (in this novel) the story that young Indian men (and women) are alcoholic deadenders with no future.

In Ceremony Silko shows the impact that these destructive stories have on members of the tribe. She describes the indoctrination schools that Indian children were once required to attend where they saw their customs and their stories ridiculed. She creates the figure of Rocky, a young Indian who is determined to be “American” rather than Indian, who scoffs at Indian rituals and enlists in World War II to fight for “his” country. She shows embittered Indian war veterans who complain incessantly about the whites but who want what the whites have and allow themselves to be defined in white terms. Finally, she gives us Tayo, the main character (and a stand-in for the author) who learns to trust the stories of his people and who is able to find a purpose for himself in those stories—and, through doing so, is able to reinvigorate the tribe.

The book begins with Tayo returned from World War II, where he has survived the Bataan death march but has seen his cousin Rocky die. Tayo is suffering from a host of problems, including PTSD, survivor guilt, a sense that he has desecrated nature (by cursing the incessant rainfall in the Philippines), and a fear that he deserted his uncle (and essential father-figure) Josiah (Josiah died while he was away). On top of that, he was abandoned by his mother when a child, was (and still is) the subject of racist taunts by his Indian buddies for his mixed blood (his father was a white man), and is subject to white racism and the stresses of being Indian in a white world. This white world, meanwhile, is suffering from the sickness that arises from its alienation from nature. So there is sickness and death as far as the eye can see, and the question is whether Indian stories can provide healing. This is the question that Silko has set herself to answering

I won’t go too deeply into the story here. But Tayo, guided by a medicine man, embarks on a quest that, in the end, helps him see a unified story of connection beyond all the fragmentation and disease. It means resisting the forces of destruction and embracing his traditions. Yet these traditions are not static rituals but evolving practices that change to take into account the pressures from the white world.

The interaction between cultures can be seen in Betonie, the medicine man who guides Tayo. Betonie, like Tayo himself (and Silko as well), has mixed blood and lives at the borderline of the white and Indian worlds. He is learning to adjust the ancient ceremonies to the changing times to help young Indians negotiate the new world in which they find themselves—just as Silko, while drawing on Laguna stories, has woven them into a European genre, the novel. And as such, she, like Betonie, is providing us all with a healing stories, non-Indians as well as Indians. Those of who who are white are challenged to leave beyond our violent and exploitative relationship with oppressed peoples and with nature and to begin to work towards deeper connections. It’s not easy, Silko says repeatedly—it requires a heroic quest. But her novel—her story—helps us see how we can work towards it.

Will it bring healing like the healing that Tayo finds in the novel? Or is this just a story? That’s the question that lies at the base of this website. What I know is that I have a feeling of hope and possibility when I read Silko’s novel.