Tuesday

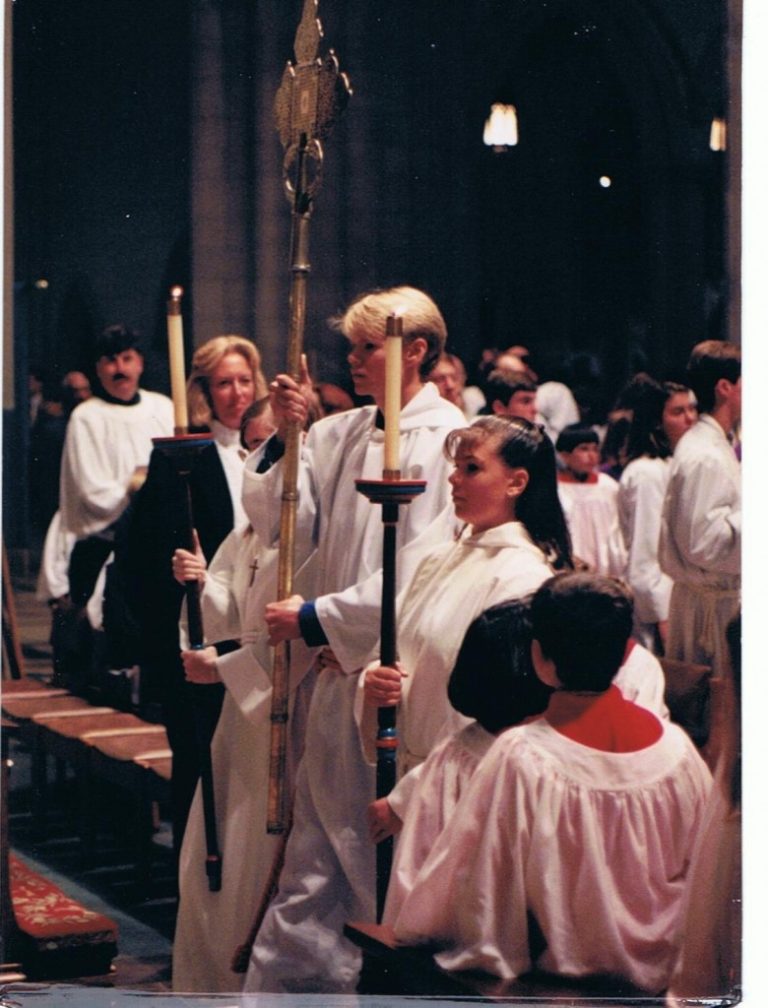

Today is the 19th anniversary of my oldest son’s death. When Justin died in a freak drowning accident in 2000, our world turned upside down. He was 21 at the time and would have been 40 this year. In “When Great Trees Fall,” Maya Angelou captures much of what I experienced.

I’m struck by her observation that, “when great souls die,/ the air around us becomes/ light, rare, sterile.” Justin was a great soul—joyous, thoughtful, and kind—and I have different ideas what Angelou means by “light.” Let me try them out.

When I was watching the divers search for the Justin’s body, my mind went to a disturbing place in that I experienced a feeling of lightness. Suddenly, I thought, the complexity of living with Justin would be lifted from my shoulders. I wouldn’t need to worry about his future after college or how much longer he would experiment with Christian fundamentalism. Looking back, I realize that I was in a state of shock. Perhaps my mind was frantically searching for ways to lighten the crash that would come later.

In Sartre’s play The Flies, Electra experiences the heaviness of her guilt at having killed Clytemnestra and longs to feel light again. In André Malraux’s novel La Condition Humaine, one character feels exhilarated when he returns home to find that Chinese nationalists have killed his wife and child. Although he loves them, his first feeling is that the responsibilities weighing him down have disappeared. Death, at first encounter, seems to remove a lot of our tangles.

As Angelou notes, however, the air around us also becomes sterile. In Flies, Orestes counters Electra by saying that we should embrace life in all its heaviness. “We were too light before,” he tells her. As I recall, Malraux doesn’t further pursue the inner life of his character, but in my case I too turned my back on lightness and embraced the full weight of my sorrow

In doing so, I experienced the other kind of light. When great souls die, Angelou says, “Our eyes, briefly,/ see with/ a hurtful clarity.” Suddenly, everything around me vibrated with a kind of luminescence. I would gaze at the vegetation growing in our back yard and see life insisting upon itself. Although the light would eventually “dwindle to the light of common day” (Wordsworth), for about a year I vibrated to the world around me. Death had that kind of effect.

Fortunately, I didn’t have the regrets that Angelou mentions, kind words unsaid or promised walks untaken. Five days before he died, Justin came by my office, and although I was swamped by student essays (it was the last week of the semester), I pushed them aside and we talked for two hours. The next time I saw him, it was to identify his body.

Angelou gets right what happens next:

We are not so much maddened

as reduced to the unutterable ignorance

of dark, cold

caves.

I too thought of myself in a dark, cold cave, which for me was the underwater cave that Beowulf enters in search of Grendel’s Mother. I came to see her as a symbol of destructive grief, which threatens to pull us into darkness and tear our hearts out.

In an epiphanic moment that occurred two weeks after the death, I suddenly saw myself as Beowulf seized by the monster. Although I didn’t know where my grief would take me, I was determined not to resist. I was there to receive whatever she doled out, and unlike Beowulf I dispensed with my chest armor.

This meant that, when I was angry, I allowed myself to be angry. When I experienced the deepest fatigue of my life, I allowed myself to be tired. If I didn’t fight her, maybe my grief would transform from monster to guide.

At the bottom of my grief, I found my version of Beowulf’s sword. As I read the poem, Beowulf ultimately handles grief by reconnecting with his warrior identity. My own giant sword was my responsibility to be a good husband, father, and community member. My commitment to others called for me to be strong.

The ending of Angelou’s poem also rings true:

Our senses, restored, never

to be the same, whisper to us.

They existed. They existed.

We can be. Be and be

better. For they existed.

On the night that Justin died, I remember thinking that I could either let his death blight my life (and, by my actions, the lives of those I loved) or lead me to a new and better place. “Be and be better,” Angelou tells us, reminding us both to live again and to live in a new way.

After the death, I became more empathetic to students and acquaintances who were suffering. Dropping much of my emotional reserve, I became a better teacher and friend. I reached out.

For Justin existed.

Here’s the poem:

When Great Trees Fall

When great trees fall,

rocks on distant hills shudder,

lions hunker down

in tall grasses,

and even elephants

lumber after safety.

When great trees fall

in forests,

small things recoil into silence,

their senses

eroded beyond fear.

When great souls die,

the air around us becomes

light, rare, sterile.

We breathe, briefly.

Our eyes, briefly,

see with

a hurtful clarity.

Our memory, suddenly sharpened,

examines,

gnaws on kind words

unsaid,

promised walks

never taken.

Great souls die and

our reality, bound to

them, takes leave of us.

Our souls,

dependent upon their

nurture,

now shrink, wizened.

Our minds, formed

and informed by their

radiance,

fall away.

We are not so much maddened

as reduced to the unutterable ignorance

of dark, cold

caves.

And when great souls die,

after a period peace blooms,

slowly and always

irregularly. Spaces fill

with a kind of

soothing electric vibration.

Our senses, restored, never

to be the same, whisper to us.

They existed. They existed.

We can be. Be and be

better. For they existed.

Further thought: Because my feeling of lightness in the moments after Justin’s death so disturbed me, I have just looked up my father’s copy of La Condition Humaine to find the character who has a similar response to death. Hemmelrich is a humane Belgian in Shanghai with revolutionary sympathies who has saved a woman from death. He doesn’t particularly love her but feels an obligation to take care of her and the sickly child they have together. Although he wants to join the revolution, for their sake he turns away revolutionaries who come to him looking for assistance. Meanwhile the child cries incessantly.

The passage I recalled occurs after he returns to the record shop he runs and finds that it has been “scrubbed” by a grenade and that the woman’s and child’s blood are everywhere. Unexpectedly, he feels “liberated” and “exhilarated.” Here’s a rough translation (rough because my French is rusty):

This time destiny had played things badly: in tearing from him all that he possessed, she had liberated him…Despite the collapse, this sensation of a blow to the neck had lifted a weight from his shoulders and he experienced an atrocious joy, heavy and profound, of liberation…[H]e was no longer powerless. Now, he too could kill…An intense exaltation overcame him, the more powerful because he had never known it before; he abandoned himself utterly to this frightful intoxication. “One can kill with love. With love, God damn it!” he repeated, pounding his fist on the counter.

As Wordsworth once noted, one is powerless before the wayward thoughts that sometimes slide into one’s head. Rather than yielding to self-disgust, I turned to Sartre and Malraux to help me better understand my response. In my case, I doubled down on caring for my family.