Wednesday

A few weeks ago I wrote about how Donald Trump’s wall slides between the literal and the symbolic depending on which day it is. On some days the president goes into great detail about its physical features and claims that it will stop armored cars filled with drugs and duct-taped women that otherwise will drive with impunity across the border. At other times it operates as a general symbol for a new American vision, an edifice that will replace that Statue of Liberty about what America means.

In the latter case, it doesn’t matter whether such a wall would stop anyone at all. It’s a cynical response to a certain set of fears rather than a practical solution.

I therefore find myself asking, “When is a wall not a wall?” echoing a line from one of my favorite children’s books. T. H. White’s Mistress Masham’s Repose features a barrier that locks in the heroine—but which, when seen from a different angle, proves to be no barrier at all. Think of it as Trump’s wall.

To briefly outline the plot, Maria has discovered Lilliputians living on the ancient estate where she is a ward. Unfortunately, her evil guardians discover them as well and lock her up before she can warn her new friends that they are about to be captured and sold. She finds herself locked in the estate’s dungeon behind a door that appears as impenetrable as Trump’s medieval wall:

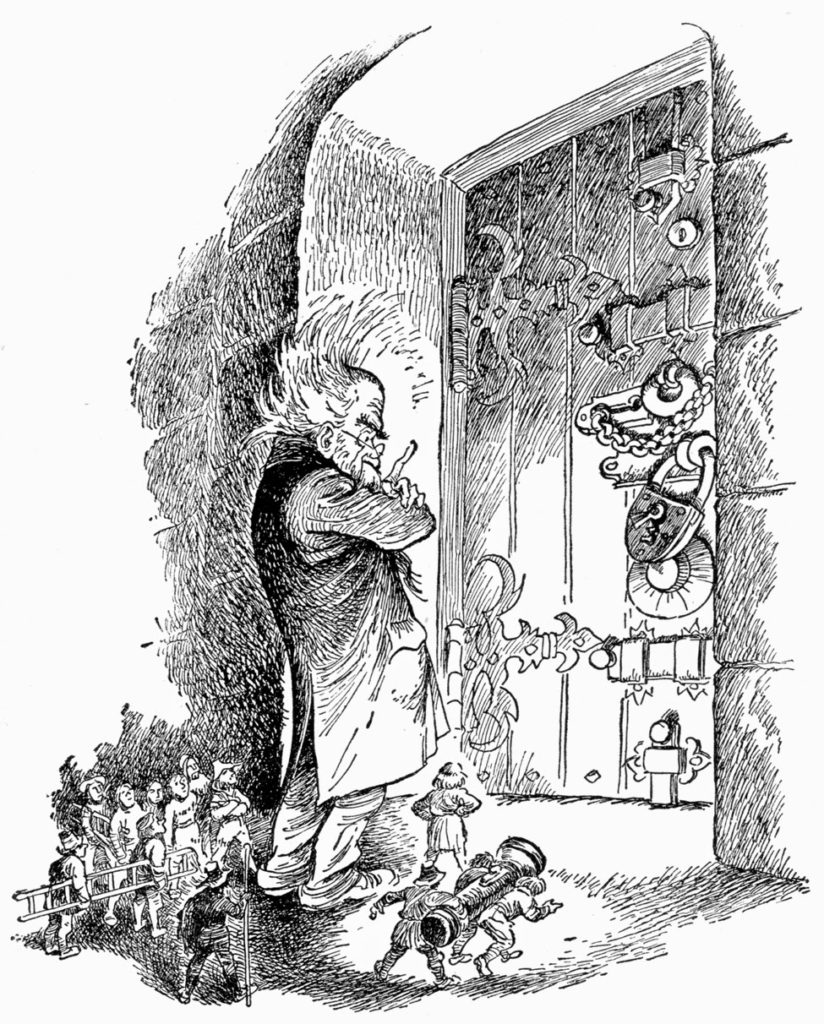

The door was battle-ax proof. It was laid together in two plies of wood, the grain of one ply being horizontal and of the other vertical, so that no ax could split it. In its early days, when it had first been set on its hinges by some feudatory of William the Conqueror’s, it had been secured by an enormous bar of wood, the size of a yule log, which had run in two wide tunnels left in the masonry of the wall. When this bar had become worm-eaten, somewhere in the reign of Queen Elizabeth, the village blacksmith had constructed a wrought-iron lock to take its place. This was still there, locked. Miss Brown had removed the key, which weighed two pounds three ounces. There were, from the same period, some handsome iron bolts. These offered no difficulty, because they had only to be drawn, if one happened to be on the outside. Since the days of Elizabeth, various other people had done their best for the security of the hold. Under the Regency, somebody had fixed iron bars, like the bars for windows, but these could be shifted like the bolts. Under Queen Victoria somebody else had put on the kind of chain which people have for front doors. Under King Edward, an expert had come down from the Bank of England, and had provided a circular lock which nobody on earth could open, unless he knew the key word for the combination, which happened to be “Mnemosyne.” (One of the dukes had won the Derby with a horse of that name; the bookies had called it “N or M.”) Under King George V, an American gentleman had sold the reigning duke a ten-shilling lock by Yale. Under King George VI, the whole affair had been provided with strips of antigas and black-out paper, by means of which it could be stuck together. The door was shut.

So how will Maria’s tutor and the Lilliputians spring her free? They must show that the door, as Democrats are trying to show with the wall, will not operate as intended. The professor turns to his impressive brain for help:

Now, as he stood outside the dungeon, his skull could almost be seen to swell and rise like a football being inflated. His white hair stood on end like a thunder-stricken cat’s, when stroked; his eyes sank into their sockets with the effort of concentration; the veins on the side of his temples throbbed like a frog’s heart beating; the temples themselves lifted like a cockchafer’s wing cases, when about to fly.

The door shook on its hinges.

“Exactly,” said the Professor. “Now here we have a door. Pray stand in front, most erudite Schoolmaster, to assist my meditations.”

The Lilliputians fell back in awe, not of his size but of his mental powers, and the Schoolmaster stepped forward solemnly to do his best, feeling proud that he had lived to see that day.

“When,” said the Professor, stroking his beard with majesty and glaring upon the lock, “is a door not a door? This is the conundrum which we, among others, and not for the first time, are called upon to determine. Hic labor, hoc opus est.” [This is the task, this is the hard part.]

He arrives as the answer:

“When,” he repeated, “is a door not a door?”

“Tibi ipsi, non mihi,” said the Schoolmaster reverently, meaning “I will buy it.”

“When it is off its hinges.”

At that point, it’s a fairly simple matter to pry the ancient hinges off the door with a crowbar and liberate the captive. White explains,

The old gentleman might have gone on to point out that most locks and bolts are really a kind of bluff, that fox hunters who are confronted by a chained gate have only to lift it from the other end, and that the human race will generally be fascinated by a padlock as if it were a rattlesnake, instead of going round another way, or climbing through the window.

While the plot has several more twists and turns, good ultimately prevails as the forces of evil are vanquished.

Democrats are publicly declaring and many Republicans are privately admitting that Trump’s wall will be no more effective. Most drugs pass through legal points of entry and most migrants aren’t trying to escape detection—they want to turn themselves into authorities as they ask for asylum.

If walls are defined by their ability to keep people out, then Trump’s wall is not a wall.