Spiritual Sunday

Years ago, when I was skeptical of Christianity, Episcopalian rector Bill Pregnall invited me to an on-going conversation. Every two weeks or so we got together and discussed ethical issues, the meaning of life, and various other matters. Not once did he push me to convert, choosing instead to listen to my reservations about religion and my questions about the Bible. At one point, when I was complaining about the sterility of modern society, he said, “Perhaps you are hungry for mystery.”

I knew, at some deep level, he was right and I began joining Julia at church. The luminescent author Nicole Krause describes this hunger in Forest Dark, our current book group selection.

The novel alternates between a Jewish billionaire and his daughter Maya. At one point we learn about an unusual bat mitzvah request:

Long ago, at Maya’s bat mitzvah party, they’d had a palm reader. Never mind the unkosher presence of the occult: it was what she had wanted. (“What do you love most, Mayashka?” he’d once asked her as a little child. “Magic and mystery,” she replied without pause.”)

Now a novelist, Maya still hungers for magic and mystery. As a result, she is disturbed when a physicist propounds a multiverse theory:

[I]f there is not one but an infinite or nearly infinite set of worlds, each with its own physical laws, then no condition can any longer be considered the result of extraordinary mathematical improbabilities.

In Maya’s eyes, the theory robs the universe of wonder:

I’d never allowed myself to believe in God, but I could see why theories of a multiverse could get under a certain kind of person’s skin—if nothing else, to say that everything might be true somewhere not only carried the whiff of evasion but also rendered any searching useless, since all conclusions become equally valid. Doesn’t part of the awe that fills us when we confront the unknown come from understanding that, should it at last flood into us and become known, we would be altered? In our view of the stars, we find a measure of our own incompleteness, our still-yet unfinishedness, which is to say, our potential for change, even transformation. That our species is distinguished from others by our hunger and capacity for change has everything to do with our ability to recognize the limits of our understanding, and to contemplate the unfathomable.

In a multiverse, on the other hand,

the concepts of known and unknown are rendered useless, for everything is equally known and unknown. If there are infinite worlds and infinite sets of laws, then nothing is essential, and we are relieved from straining past the limits of our immediate reality and comprehension, since not only does what lies beyond not apply to us, there is also no hope of gaining anything more than infinitesimally small understanding. In that sense, the multiverse theory only encourages us to know our backs even further on the unknowable, which we’re more than happy to do, having become drunk on our powers of knowing—having made a holiness out of knowing, and busying ourselves all day and night in our pursuit of it.

As a young professor, I was drunk on literary theory, but I also sensed that such knowing, in and of itself, was empty. That is why I sought out Bill’s conversations. I recognize my younger self in Maya’s continuing reflection:

Just as religion evolved as a way to contemplate and live before the unknowable, so now we have converted to the opposite practice, to which we are no less devoted: the practice of knowing everything, and believing that knowledge is concrete, and always arrived at through the faculties of the intellect. Since Descartes, knowledge has been empowered to a nearly unimaginable degree. But in the end it didn’t lead to the mastery and possession of nature he imagined, only to the illusion of its mastery and possession. In the end, we have made ourselves ill with knowledge. I frankly hate Descartes, and have never understood why his axiom should be trusted as an unshakable foundation for anything. The more he talks about following a straight line out of the forest, the more appealing it sounds to me to get lost in that forest, where once we lived in wonder, and understood it to be a prerequisite for an authentic awareness of being and the world. Now we have little choice but to live in the arid fields of reasons, and as for the unknown, which once lay glittering at the farthest edge of our gaze, channeling our fear but also our hope and longing, we can only regard it with aversion.

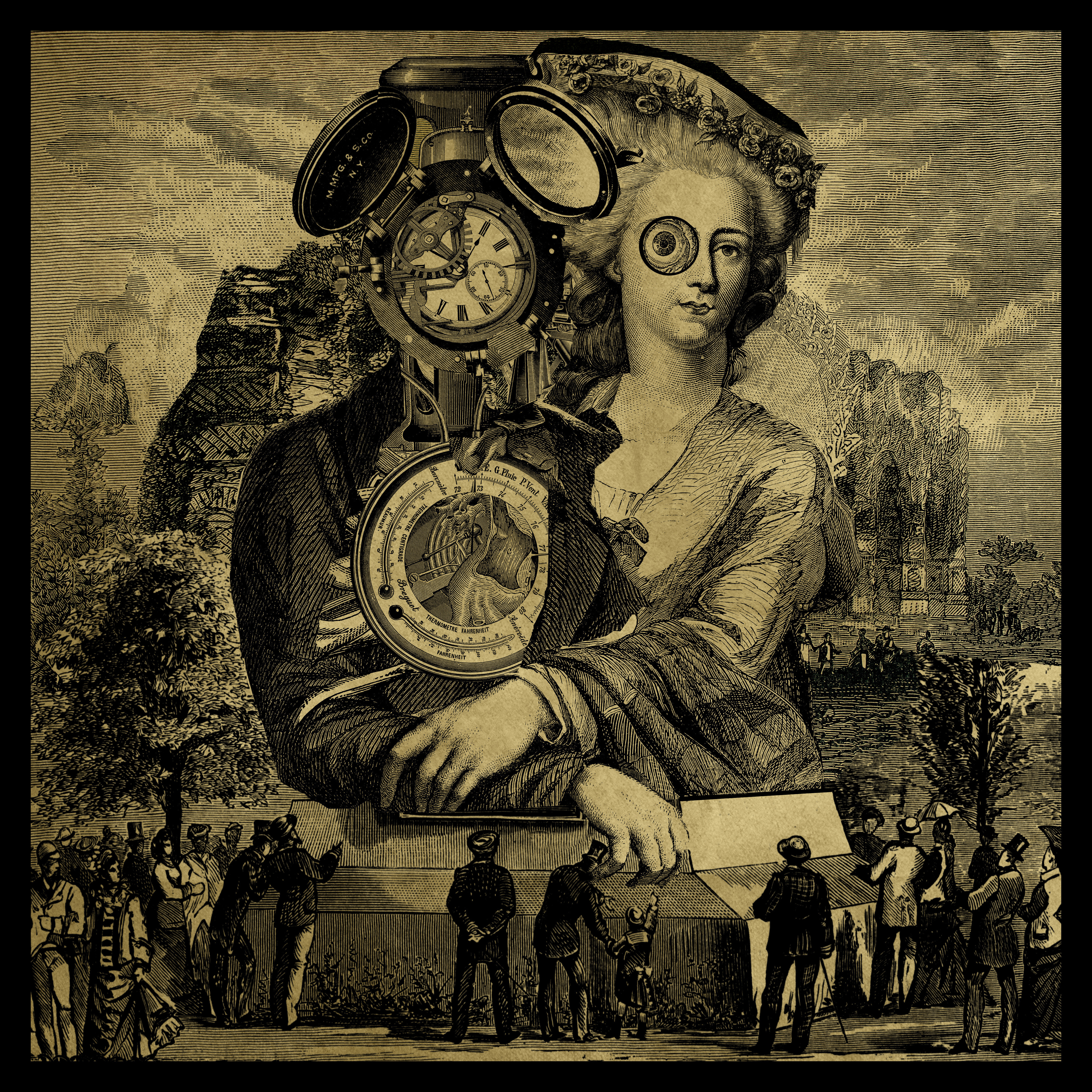

In the 18th century, the Enlightenment led to the rise of the gothic novel as people found refuge from the blinding light of Reason in supernatural shadows. As I met with my British fantasy class for one last time yesterday, we talked about the hunger that leads them to authors like J. R. R. Tolkien, C. S. Lewis, Philip Pullman, Diane Wynne Jones, Neil Gaiman, and Terry Pratchett. I told them to take their attraction seriously.

I don’t reject Reason, but I no longer see it as the ultimate key to understanding the universe. Instead, I look for meaning through a combination of intellectual probing, religious worship, engaging with the arts (especially literature), and fostering relationships with loved ones, friends, and acquaintances. Oh, and playing tennis.

I’ve only begun Krauss’s novel so I can’t report on Maya’s endpoint. But I identify with her search.

Further thought: “Forest Dark” may echo Dante’s dark wood but, in a reversal, Krauss says that being “lost in that forest” promises a return to wonder and “authentic awareness.”