Tuesday

On Friday I warned about the dangers of leftwing purists who believe that only members of a particular demographic group should write about that group. In her 1997 book Cultivating Humanity: A Classical Defense of Reform in Liberal Education, Chicago philosopher Martha Nussbaum makes a similar argument. To reduce literature to political identity, she says, is to ignore its greatest asset, which is the ability “to cross group boundaries in imagination.”

Nusbaum differentiates between world citizenship and identity politics. To become a world citizen, one must journey outside one’s own group, and Nussbaum believes that literature is the ideal vehicle. Identity politics, on the other hand, is “antihumanist” because it celebrates difference “in an uncritical way,” denying “the very possibility of common interests and understanding”:

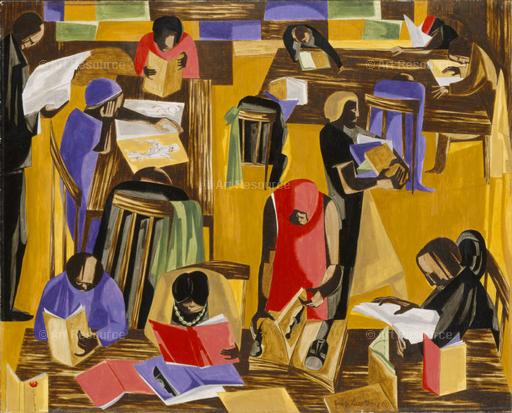

In the world-citizen version of multiculturalism, the ethical argument for adding a work such as Invisible Man to the curriculum will be Ellison’s own argument that our nation has a history of racial obtuseness and that this work helps all citizens to perceive racial issues with great clarity. In the identity-politics version of multiculturalism, by contrast, the argument in favor of Invisible Man will be that it affirms the experience of African-American students. This view denies the possibility of the task Ellison set himself: “of revealing the human universals hidden within the plight of one who was both black and American.”

Nussbaum doesn’t entirely deny the significance of one’s group identity. “If we want to understand the situation of a group,” she writes at one point, “we do well to begin with the best that has been written by members of that group.” She also says we must take identity seriously rather than facilely asserting that “we are all alike under the skin”:

Experience and culture shape many aspects of what is “under the skin,” as we can easily see if we reflect and read.

She is concerned, however, that identity politics in the end traps us within our separate identities. Literature is vital, she argues, because it “expands sympathies that real life cannot cultivate sufficiently”:

It is the political promise of literature that it can transport us, while remaining ourselves, into the life of another, revealing similarities but also profound differences between the life and thought of that other and myself and making them comprehensible, or at least more nearly comprehensible. Any stance toward criticism that denies that possibility seems to deny the very possibility of literary experience as a human social good.

And:

[T]he great contribution literature has to make to the life of the citizen is its ability to wrest from our frequently obtuse and blunted imaginations an acknowledgement of those who are other than ourselves, both in concrete circumstances and even in thought and emotion. As Ellison put it, a work of fiction may contribute “to defeat this national tendency to deny the common humanity shared by my character and those who might happen to read of his experience.” This contribution makes it a key element in higher education.

Though those practicing separatist identity politics in literature departments often claim to be of the left, Nussbaum sees them as ultimately conservative, retreating into cloistered selves. Literature, she says, should be used to advance a far more radical vision:

[I]t is always radical, in any society, to insist on the equal worth of all human beings, and people find all sorts of ways to avoid the claim of that ideal, much though they may pay it lip service. The current agenda is radical in the way that Stoic world citizenship was radical in a Rome built on hierarchy and rank, in the way that the Christian idea of love one’s neighbor was and is radical, in a world anxious to deny our common membership in the kingdom of ends or the kingdom of heaven.

As I said in Friday’s post, the key is to establish truly diverse communities so that writers and readers, scholars and students, both share their different perspectives and find commonalities. This is more vital than ever at a moment when we are experiencing identity politics in the virulent form of white nationalism. Those in the resistance must form alliances, not insist on separateness. Literature will help us do so.