Note: If you wish to receive, via e-mail, (1) my weekly newsletter or (2) daily copies of these posts, write to me at rrbates1951@gmail.com. Comments may also be sent to this address. I promise not to share your e-mail with anyone. To unsubscribe, write here as well.

Wednesday

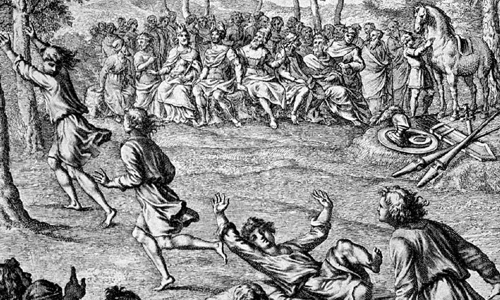

As the Olympic games have me looking up classical references (see yesterday’s post), here’s the description of the foot race in The Aeneid, held in honor of the recent death of Aeneas’s father Anchises. Note that it’s a much more chaotic affair than our own races—although having said that, I notice that there was controversy in the women’s 5000 meter race yesterday involving a Kenyan and an Ethiopian runner. The Ethiopian accused Faith Kipyegon of obstructing her during the race, which led to Kipyegon being stripped of her silver medal, although it was later restored on appeal.

In Virgil’s race, one runner has the race all but won until he has an unfortunate mishap involving blood on the track:

[O]n hearing the signal, they left the barrier and shot onto the course,

streaming out like a storm cloud, gaze fixed on the goal.

Nisus was off first, and darted away, ahead of all the others,

faster than the wind or the winged lightning-bolt:

Salius followed behind him, but a long way behind:

then after a space Euryalus was third: Helymus

pursued Euryalus, and there was Diores speeding near him,

now touching foot to foot, leaning at his shoulder:

if the course had been longer he’d have

slipped past him, and left the outcome in doubt.

Now, wearied, almost at the end of the track,

they neared the winning post itself, when the unlucky Nisus

fell in some slippery blood, which when the bullocks were killed

had chanced to drench the ground and the green grass.

Here the youth, already rejoicing at winning, failed to keep

his sliding feet on the ground, but fell flat,

straight in the slimy dirt and sacred blood.

Realizing he can’t win, Nisus figures that he can at least help out his lover Euryalus, who is also in the race. (Euryalus, we’ve learned earlier, is “famed for his beauty, and in the flower of his youth.”)Therefore he deliberately trips up one of their competitors:

But [Nisus] didn’t forget Euryalus even then, nor his love:

but, picking himself up out of the wet, obstructed Salius,

who fell head over heels onto the thick sand.

As a result, Euryalus is first across the finish line:

Euryalus sped by and, darting onwards to applause and the shouts

of his supporters, took first place, winning with his friend’s help.

Helymus came in behind him, then Diores, now in third place.

Needless to say, Salius does not take this well:

At this Salius filled the whole vast amphitheatre, and the faces

of the foremost elders, with his loud clamour,

demanding to be given the prize stolen from him by a trick.

So what is the referee (Aeneas) to do? He comes close to using the Dodo’s strategy in Alice in Wonderland following the confusing race amongst all the animals that have fallen into the pool of tears: “Everyone has won and all must have prizes.” This means giving Salius a consolation prize:

Then Aeneas the leader said, “Your prizes are still yours,

lads, and no one is altering the order of attainment:

but allow me to take pity on an unfortunate friend’s fate.

So saying he gives Salius the huge pelt of a Gaetulian lion,

heavy with shaggy fur, its claws gilded.

But if Aeneas is giving out pity awards, then Nisus figures he deserves somethng as well. After all, he would have won had he not slipped in the ceremonial blood. No problem, says Aeneas:

At this Nisus comments: “If these are the prizes for losing,

and you pity the fallen, what fitting gift will you grant to Nisus,

who would have earned first place through merit

if ill luck had not dogged me, as it did Salius?”

And with that he shows his face and limbs drenched

with foul mud. The best of leaders smiles at him,

and orders a shield to be brought, the work of Didymaon,

once unpinned by the Greeks from Neptune’s sacred threshold:

this outstanding prize he gives to the noble youth.

By this time, it’s starting to sound like Aeneas is handing out participation trophies, which I remember well from when I was coaching my kids’ soccer teams. These were important for when the kids were little, but it didn’t take long for the adults—and even some of the kids—to become heartily sick of them.

Then again, we weren’t giving the kids shields and horses. Or, as Aeneas does following a sailing race, a Cretan born slave-girl. Seen in this light, the modern Olympic committee is getting away cheap by limiting its awards to gold, silver and bronze medals.

Further thought: Virgil tells us that Euryalus, who won only because his lover cheated on his behalf, might not have fared quite so well had he not been so good looking. We are told, “His popularity protects Euryalus, and fitting tears,/ and ability is more pleasing in a beautiful body.” Some things never change.