Friday

I somehow missed this New Yorker article on Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein when it appeared last year in observance of the novel’s 200th anniversary. Although anti-Trump pundits have frequently cited Frankenstein in recent years to capture how the GOP created a monster it couldn’t control (see here and here), Joan Lepore argues that the novel features a more complex political conversation.

In this scenario, Victor Frankenstein represents a conservative perspective and his “creature” a radical one. Since the novel features multiple narrators, both perspectives are given a hearing. It’s useful to note that Shelley herself leaned radical, as did her parents. Mary Wollstonecraft was one of the founders of feminism with her Vindication of the Rights of Women while William Godwin was a fierce defender of “political justice.”

First, here’s where the novel leans right:

If Frankenstein is a referendum on the French Revolution, as some critics have read it, Victor Frankenstein’s politics align nicely with those of Edmund Burke, who described violent revolution as “a species of political monster, which has always ended by devouring those who have produced it.”

The unnamed creature, by contrast, sees injustice at work in the world:

Watching the cottagers read a book, Ruins of Empires, by the eighteenth-century French revolutionary the Comte de Volney, he both learned how to read and acquired “a cursory knowledge of history”—a litany of injustice. “I heard of the division of property, of immense wealth and squalid poverty; of rank, descent, and noble blood.” He learned that the weak are everywhere abused by the powerful, and the poor despised.

This view aligns him with Shelley’s parents:

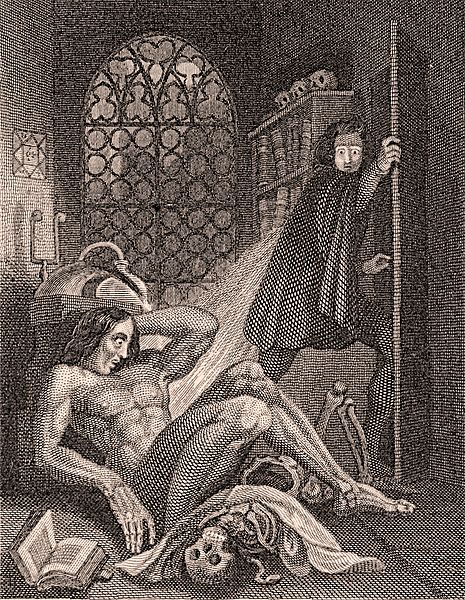

The creature’s own politics, though, align not with Burke’s but with those of two of Burke’s keenest adversaries, Mary Wollstonecraft and William Godwin. Victor Frankenstein has made use of other men’s bodies, like a lord over the peasantry or a king over his subjects, in just the way that Godwin denounced when he described feudalism as a “ferocious monster.” (“How dare you sport thus with life?” the creature asks his maker.) The creature, born innocent, has been treated so terribly that he has become a villain, in just the way that Wollstonecraft predicted. “People are rendered ferocious by misery,” she wrote, “and misanthropy is ever the offspring of discontent.” (“Make me happy,” the creature begs Frankenstein, to no avail.)

If we find ourselves relating more with the creature than with the creator, it’s because Shelley crafts the book with that intent:

Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin Shelley took pains that readers’ sympathies would lie not only with Frankenstein, whose suffering is dreadful, but also with the creature, whose suffering is worse. The art of the book lies in the way Shelley nudges readers’ sympathy, page by page, paragraph by paragraph, even line by line, from Frankenstein to the creature, even when it comes to the creature’s vicious murders, first of Frankenstein’s little brother, then of his best friend, and, finally, of his bride. Much evidence suggests that she succeeded. “The justice is indisputably on his side,” one critic wrote in 1824, “and his sufferings are, to me, touching to the last degree.”

In short, if conservatives don’t want to unleash a French Revolution-style reign of terror, they need to clean up their act.

Along these lines, Lepore points out that Frankenstein can also be read as an anti-slave work. Although Frederick Douglass was born a year after the novel appeared, the creature’s education and dawning realization very much resemble Douglass’s own evolution:

[T]he creature comes of age when he finds Frankenstein’s notebook, recounting his experiment, and learns how he was created, and with what injustice he has been treated. It’s at this moment that the creature’s tale is transformed from the autobiography of an infant to the autobiography of a slave. “I would at times feel that learning to read had been a curse rather than a blessing,” Douglass wrote. “It had given me a view of my wretched condition, without the remedy.” So, too, the creature: “Increase of knowledge only discovered to me more clearly what a wretched outcast I was.” Douglass: “I often found myself regretting my own existence, and wishing myself dead.” The creature: “Cursed, cursed creator! Why did I live?” Douglass seeks his escape; the creature seeks his revenge.

Lepore points out that Mary and her husband Percy were both abolitionists, although they took a gradualist approach. Percy is on record favoring

not immediate but gradual emancipation, fearing that the enslaved, so long and so violently oppressed, and denied education, would, if unconditionally freed, seek a vengeance of blood. He asked, “Can he who the day before was a trampled slave suddenly become liberal-minded, forbearing, and independent?”

From this perspective, then, Frankenstein finds a middle ground between conservative and radical positions.

But put aside political oppression for a moment and look at the novel as a reflection upon childbirth and child rearing. Mary Shelley, Lepore points out, differs from such authors as Jane Austen, Emily Dickinson, and the Brontes in that she was having—and losing—babies while she was writing. Her own birth, meanwhile, had resulted in the death of her mother (from the doctor’s infected fingers removing the afterbirth). Therefore, it makes sense that the novel would feature a monstrous birth and the resulting complications. In some ways, the creature goes bad because Victor Frankenstein fails to love, care for and educate him.

Lepore points this out to challenge those who see the work as a parable about out-of-control technology. Such readings, she says strip out “nearly all the sex and birth, everything female” from the work:

Most lately, it has been taken as a cautionary tale for Silicon Valley technologists, an interpretation that derives less from the 1818 novel than from later stage and film versions, especially the 1931 film, and that took its modern form in the aftermath of Hiroshima. In that spirit, M.I.T. Press has just published an edition of the original text “annotated for scientists, engineers, and creators of all kinds,” and prepared by the leaders of the Frankenstein Bicentennial Project, at Arizona State University, with funding from the National Science Foundation; they offer the book as a catechism for designers of robots and inventors of artificial intelligences. “Remorse extinguished every hope,” Victor says, in Volume II, Chapter 1, by which time the creature has begun murdering everyone Victor loves. “I had been the author of unalterable evils; and I lived in daily fear, lest the monster whom I had created should perpetrate some new wickedness.” The M.I.T. edition appends, here, a footnote: “The remorse Victor expresses is reminiscent of J. Robert Oppenheimer’s sentiments when he witnessed the unspeakable power of the atomic bomb. . . . Scientists’ responsibility must be engaged before their creations are unleashed.”

Such a reading isn’t entirely wrong since Frankenstein does play god. (Oppenheimer quoted the Bhagavad-Gita following the bomb’s successful detonation: “Now I have become Death, the destroyer of worlds.”) The novel’s debt to Paradise Lost points to the theme of overweening pride.

All of which is to say that, like all great novels, Frankenstein operates on many levels. To name one final one in line with the central theme of this blog, it shows how the classics make a difference in the lives of readers:

Shelley kept careful records of the books she read and translated, naming title after title and compiling a list each year—Milton, Goethe, Rousseau, Ovid, Spenser, Coleridge, Gibbon, and hundreds more, from history to chemistry. “Babe is not well,” she noted in her diary while writing Frankenstein. “Write, draw and walk; read Locke.” Or, “Walk; write; read the Rights of Women.” The creature keeps track of his reading, too, and, unsurprisingly, he reads the books that Shelley read and reread most often. One day, wandering in the woods, he stumbles upon a leather trunk, lying on the ground, that contains three books: Milton’s Paradise Lost, Plutarch’s Lives, and Goethe’s The Sorrows of Young Werther—the library that, along with Volney’s Ruins, determines his political philosophy…

So books provide understanding although, if we are not go off the rails, we must also be wise in how we apply this powerful knowledge. After all, these works don’t deter the creature from engaging in a string of murders. But are the books really at fault? If he had really listened to Young Werther, he would have realized that letting your emotions run rampant is an indulgence that leads to loss of self.

Meanwhile, his creator could have learned, from Paradise Lost, the soul-emptying result of trying to play God.