Wednesday

A former student alerted me to this Atlantic article arguing that Britain produces better fantasy than America and giving the reasons why. While the piece is stimulating and helps me understand why I myself preferred British fantasy as a child, author Colleen Gillard makes a number of questionable claims. Above all, she defines fantasy in a particularly British way, meaning that American fantasy starts off at an immediate disadvantage.

Gillard sets up the contrast as follows:

The small island of Great Britain is an undisputed powerhouse of children’s bestsellers: The Wind in the Willows, Alice in Wonderland, Winnie-the-Pooh, Peter Pan, The Hobbit, James and the Giant Peach, Harry Potter, and The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe. Significantly, all are fantasies. Meanwhile, the United States, also a major player in the field of children’s classics, deals much less in magic. Stories like Little House in the Big Woods, The Call of the Wild, Charlotte’s Web, The Yearling, Little Women, and The Adventures of Tom Sawyer are more notable for their realistic portraits of day-to-day life in the towns and farmlands on the growing frontier. If British children gathered in the glow of the kitchen hearth to hear stories about magic swords and talking bears, American children sat at their mother’s knee listening to tales larded with moral messages about a world where life was hard, obedience emphasized, and Christian morality valued. Each style has its virtues, but the British approach undoubtedly yields the kinds of stories that appeal to the furthest reaches of children’s imagination.

Gillard goes on and on about the Puritanical moralism of American children’s literature and sees British fantasy as exempt. I’ll question this in a moment but let’s allow her to first make her point:

It all goes back to each country’s distinct cultural heritage. For one, the British have always been in touch with their pagan folklore, says Maria Tatar, a Harvard professor of children’s literature and folklore. After all, the country’s very origin story is about a young king tutored by a wizard. Legends have always been embraced as history, from Merlin to Macbeth. “Even as Brits were digging into these enchanted worlds, Americans, much more pragmatic, always viewed their soil as something to exploit,” says Tatar. Americans are defined by a Protestant work ethic that can still be heard in stories like Pollyanna or The Little Engine That Could.

And:

American fantasies differ in another way: They usually end with a moral lesson learned—such as, surprisingly, in the zany works by Dr. Seuss who has Horton the elephant intoning: “A person’s a person no matter how small,” and, “I meant what I said, and I said what I meant. An elephant’s faithful one hundred percent.” Even The Cat in the Hat restores order from chaos just before mother gets home.

When my colleague Donna Richardson heard the argument that British fantasy isn’t moralistic, she all but snorted, asking, “Narnia, anyone?” She remembered finding C. S. Lewis “too preachy” when she was a child.

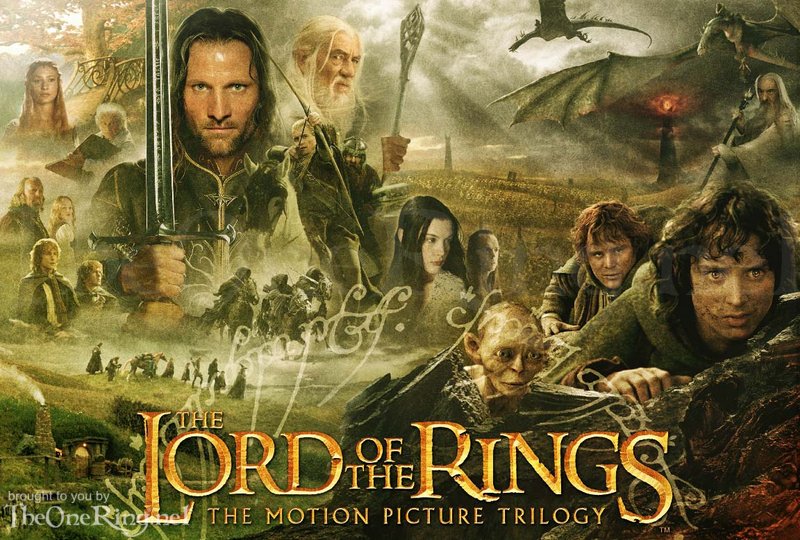

Nor is Lewis alone. Lord of the Rings sets up Frodo as a Christ figure and I have had a student convincingly argue that a major influence on Tolkien’s fantasy is Pilgrim’s Progress, by the Puritan preacher John Bunyan. Harry Potter also undergoes a Christ-like resurrection in the final book, overcoming Voldemort’s destructive hatred with Christian compassion. Therefore, I’m not buying Gillard’s assertion that

a world not fixated on atonement and moral imperatives is more conducive to a rousing tale.

Lewis, Tolkien and Rawlings are no less fixated on atonement and moral imperatives than many American writers. And incidentally, this fixation does not prevent them from composing rousing tales.

For that matter, there is a strong moral in Wind in the Willows, despite Gillard’s claim that it is exempt from such narrowness. She sets up a Puritan-pagan contrast after interviewing a Scottish child who is enthralled with Toad’s wild ways but bored by all the rules in Little House in the Big Woods. Gillard sees Toad as a liberating trickster figure:

Pagan folktales are less about morality and more about characters like the trickster who triumphs through wit and skill: Bilbo Baggins outwits Gollum with a guessing game; the mouse in the The Gruffalo avoids being eaten by tricking a hungry owl and fox. Griswold calls tricksters the “Lords of Misrule” who appeal to a child’s natural desire to subvert authority and celebrate naughtiness: “Children embrace a logic more pagan than adult.”

Wind and the Willows has an adult message, however: If the landowning gentry acts as irresponsibly as Toad, then the working class weasels and stoats will take over the society. The book ends with the restoration of traditional classes, not with the Lord of Misrule in control. The Jungle Book ends similarly. These stories are no less in favor of final stability than is Where the Wild Things Are, which Gillard disparages in the same way she disparages Dr. Seuss.

While I disagree with Gillard on the fantasies’ moral messages, however, American and British stories do indeed have a different feel to them and I like some of her explanations. For instance, she emphasizes the different landscapes, domesticated countryside vs. the frontier:

Britain’s antique countryside, strewn with moldering castles and cozy farms, lends itself to fairy-tale invention. As Tatar puts it, the British are tuned in to the charm of their pastoral fields: “Think about Beatrix Potter talking to bunnies in the hedgerows, or A.A. Milne’s Winnie-the-Pooh wandering the Hundred Acre Wood.” Not for nothing, J.K. Rowling set Harry Potter’s Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and Wizardry in the spooky wilds of the Scottish Highlands. Lewis Carroll drew on the ancient stonewalled gardens, sleepy rivers, and hidden hallways of Oxford University to breathe life into the whimsical prose of Alice in Wonderland.

And then there’s Britain’s long, multi-layered history. I particularly like the article’s explanation for the many portal fantasies one finds in British fantasy:

Britain’s pagan religions and the stories that form their liturgy never really disappeared, the literature professor Meg Bateman told me in an interview on the Isle of Skye in the Scottish Highlands. Pagan Britain, Scotland in particular, survived the march of Christianity far longer than the rest of Europe. Monotheism had a harder time making inroads into Great Britain despite how quickly it swept away the continent’s nature religions, says Bateman, whose entire curriculum is taught in Gaelic. Isolated behind Hadrian’s Wall—built by the Romans to stem raids by the Northern barbarian hordes—Scotland endured as a place where pagan beliefs persisted; beliefs brewed from the religious cauldron of folklore donated by successive invasions of Picts, Celts, Romans, Anglo-Saxons, and Vikings.

Even well into the 19th and even 20th centuries, many believed they could be whisked away to a parallel universe. Shape shifters have long haunted the castles of clans claiming seals and bears as ancestors. “Gaelic culture teaches we needn’t fear the dark side,” Bateman says. Death is neither “a portal to heaven nor hell, but instead a continued life on earth where spirits are released to shadow the living.” A tear in this fabric is all it takes for a story to begin. Think Harry Potter, The Chronicles of Narnia, The Dark Is Rising, Peter Pan, The Golden Compass—all of which feature parallel worlds.

Bateman notes that the Puritans rejected much of Britain’s rich folklore when they went to the new world, and they did not build upon the folk traditions of the Indians or the African slaves. But rather than obliterating fantasy, their decision led to a different kind of fantasy. America’s gothic tradition is one of its major contributions to world literature.

I have in mind the gothic fantasies of Irving, Poe, and Hawthorne and, later, Stephen King. These are not children’s fantasies along the lines of Tolkien or Lewis but they are fantasies nonetheless, and children are often fascinated by them.

Whether child or adult, we all need fantasy, and America has provided us with vital stories no less than Britain.

Further thoughts: I should have explained the relationship between the suppression of the Indians and the rise of American gothic. The Puritans may have come to America denying the existence of green men and fairies, but they very much believed in Satan and (as one sees in a gothic tale like Hawthorne’s “Young Goodman Brown”) projected Satan onto the cultural Other. America’s gothic vision functions as a corrective (as fantasy often does) to John Winthrop’s sunny vision of America as a city on a hill. When a culture tries to banish shadows, they show up as nightmares, the return of the repressed. Stephen King understands this well, and the gothic horror that he sees underlying America’s Leave It to Beaver towns is often associated with America’s violent history of subjugating minorities.

And another thought: America has its own mortal fantasies, foremost amongst them The Wizard of Oz. It’s not only Brits who think they can be whisked away. It’s interesting that the instrument in Baum is an extreme weather event, more in keeping with the wildness of the American frontier. And when the Connecticut Yankee is sent back to Camelot in Twain’s novel, it arises out of a violent labor dispute between boss and worker. The American setting is much more rough and tumble than the British, giving its fantasies a rawer and less refined edge. Maybe that’s the major difference.