Monday

With all the ills that beset us, the most worrisome remains climate change, which is currently wreaking havoc in Pakistan, with its catastrophic flooding, and California, with its record temperatures and uncontrollable wild fires. Extreme climate events have also led to international incidents, such as the Syrian civil war (begin in 2011) and the northward migrations of Central Americans.

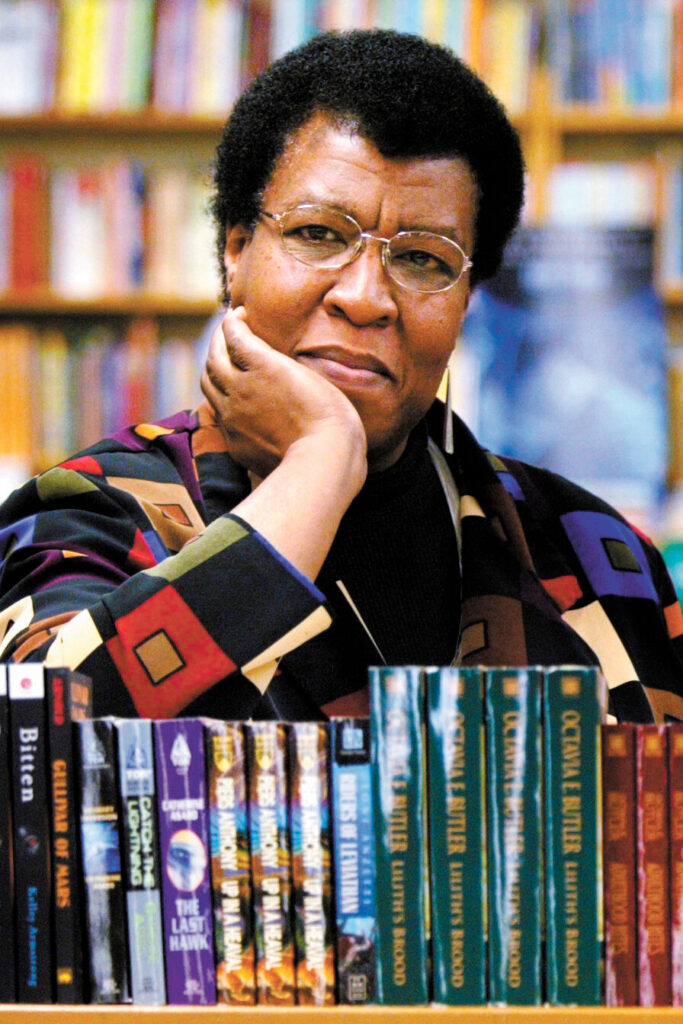

Science fiction author Octavia Butler predicted such incidents in her 1993 novel Parable of the Sower, set in 2024. Two weeks ago I posted on the narrator’s spiritual vision in the novel. Now that I’ve finished reading it, I can talk more about Butler’s vision of the havoc climate change will wreak upon social relations.

In some ways, Sower reads like a lot of post-apocalyptic fiction, like Walter Miller’s Canticles for Liebowitz and Russell Hoban’s Riddley Walker, dystopian visions of people living in a world that has experienced nuclear holocaust. Novels that have followed Butler’s have been Margaret Atwood’s Oryx and Crake trilogy and Cormac McCarthy’s The Road. All of these novels feature a society that has descended to the state of nature described by political philosopher Thomas Hobbes in his 1651 work Leviathan:

Whatsoever therefore is consequent to a time of Warre, where every man is Enemy to every man; the same is consequent to the time, wherein men live without other security, than what their own strength, and their own invention shall furnish them withall. In such condition, there is no place for Industry; because the fruit thereof is uncertain; and consequently no Culture of the Earth; no Navigation, nor use of the commodities that may be imported by Sea; no commodious Building; no Instruments of moving, and removing such things as require much force; no Knowledge of the face of the Earth; no account of Time; no Arts; no Letters; no Society; and which is worst of all, continuall feare, and danger of violent death; And the life of man, solitary, poore, nasty, brutish, and short.

In Sower, urban communities retreat behind walls to protect themselves from marauders, nihilists, and young people high on “pyromania,” a drug whose effects are enhanced by watching fires. As a result, there are non-stop cases of arson, along with wholesale slaughter. Lauren Oya Olamina, an African American teenager living in the outskirts of Los Angeles, is the only one in her family to escape when homicidal pyromaniacs assault her compound. She therefore sets out for Washington or even Canada, where climate change hasn’t wiped out the water supply. No one knows who is trustworthy—people may appear to be friends, only to murder you in your sleep for your shoes and bottled water—but she manages to assemble a community, which fend off attacks as they journey northward.

Complicating Lauren’s challenges is the fact that, because her mother abused drugs during her pregnancy, Lauren is hyper-empathetic, which means that she feels the pain of those around her. This means that, when she uses violence against those attacking her, she feels her own blows. I suspect she is a stand-in for the super-sensitive author, who acutely feels people’s assaults on the environment and on each other.

What sets Butler’s novel apart from other post-apocalyptic fiction—and makes it more interesting—is how she looks to the next generation for hope. Lauren, the narrator, is developing a philosophy/religion called Earth Seed, which she hopes will help people survive and once again flourish. She sets about building a community around these principles.

A least one member of her traveling group, her future husband, is skeptical. Older, he can’t understand why Lauren has hope. Here’s an interchange between the two that gives you a sense of their challenges:

“There’s been so much dying. There’s so much more to come.”

“Not for us, I hope.”

He said nothing for a while. Then he stopped and put his hand on my shoulder to stop me. At first he only stood looking at me, almost studying my face. “You’re so young,” he said. “It seems almost criminal that you should be so young in these terrible times. I wish you could have known this country when it was still salvageable.”

It might survive,” I said, “changed, but still itself.”“No.” He drew me to his side and put one arm around me. “Human beings will survive of course. Some other countries will survive. Maybe they’ll absorb what’s left of us. Or maybe we’ll just break up into a lot of little states quarreling and fighting with each other over whatever crumbs are left. That’s almost happened now with states shutting themselves off from one another, treating state lines as national borders. As bright as you are, I don’t think you understand—I don’t think you can understand what we’ve lost. Perhaps that’s a blessing.”

And further:

He sighed. “You know, as bad as things are, we haven’t even hit bottom yet. Starvation, disease, drug damage, and mob rule have only begun. Federal, state, and local governments still exist—in name at least—and sometimes they manage to do something more than collect taxes and send in the military. And the money is still good. That amazes me. However much more you need of it to buy anything these days, it is still accepted. That may be a hopeful sign—or perhaps it’s only more evidence of what I said: We haven’t hit bottom yet.”

Counter to this is Lauren’s vision, which she expresses through poetry. Here’s one instance:

Create no images of God.

Accept the images

that God has provided.

They are everywhere,

in everything.

God is Change—

Seed to tree,

tree to forest;

Rain to river,

river to sea;

Grubs to bees,

bees to swarm.

From one, many;

from many, one;

Forever uniting, growing, dissolving—

forever Changing.

The universe

is God’s self-portrait.

And elsewhere:

Embrace diversity.

Unite—

Or be divided,

robbed,

ruled,

killed

By those who see you as prey.

Embrace diversity

Or be destroyed.

And finally:

Kindness eases change.

I have not yet read the 1998 sequel, Parable of the Talents, but you can see how prescient Butler was by the Wikipedia description. Not only does she predict the ravages of climate change, but she foresees a MAGA dictator, bolstered by white Christian nationalists, seizing control of America:

The novel is set against the backdrop of a dystopian United States that has come under the grip of a Christian fundamentalist denomination called “Christian America” led by President Andrew Steele Jarret. Seeking to restore American power and prestige, and using the slogan “Make America Great Again,” Jarret embarks on a crusade to cleanse America of non-Christian faiths. Slavery has resurfaced with advanced “shock collars” being used to control slaves. Virtual reality headsets known as “Dreamasks” are also popular since they enable wearers to escape their harsh reality.

According to the Wikipedia article, Butler had planned to write further books in the series but felt overwhelmed by the amount of research involved. I suspect the emotional toll that her vision took upon her also played a role. She reminds me in this way of Lucille Clifton—they must have known each other—since Clifton also sometimes felt her extreme empathy to be a burden. Clifton’s “water sign woman” could describe Lauren (only Lauren has to be on the move):

the woman who feels everything

sits in her new house

waiting for someone to come

who knows how to carry water

without spilling, who knows

why the desert is sprinkled

with salt, why tomorrow

is such a long and ominous word.

they say to the feel things woman

that little she dreams is possible,

that there is only so much

joy to go around, only so much

water. there are no questions

for this, no arguments. she has

to forget to remember the edge

of the sea, they say, to forget

how to swim to the edge, she has

to forget how to feel.

Like Lauren, however, Clifton pushes back against the naysayers. She too says that, if one is patient and looks at the beauty of the world, “water will come again”:

the woman

who feels everything sits in her

new house retaining the secret

the desert knew when it walked

up from the ocean, the desert,

so beautiful in her eyes;

water will come again

if you can wait for it.

she feels what the desert feels.

she waits.

Lauren might disagree only with the waiting part. Although she too believes patience is necessary, she also counsels action. Or as she puts it,

Belief

Initiates and guides action–

Or it does nothing.

And elsewhere:

A victim of God may,

Through learning adaption,

Become a partner of God,

A victim of God may,

Through forethought and planning,

Become a shaper of God.

Better that than being a victim, whether of climate change or the other ills besetting society. Completing this last poem, Lauren lays out the alternative:

Or a victim of God may,

Through shortsightedness and fear,

Remain God’s victim,

God’s plaything, God’s prey.

The choice between visionary planning and reactionary withdrawal, in other words, is up to us.