Carl Rosin, a high school teacher I admire tremendously, shares below how he will be using a recent public dust-up about a Stephen Colbert tweet to help his students understand the power and danger of satire, especially as it applies to Huckleberry Finn. I love the tweet that Carl imagines could have emerged out of Huck and Jim’s debate over King Solomon.

Carl argues that context is everything, which is absolutely right. At the same time, he makes the point that satire always risks being misunderstood. If it didn’t take chances, it wouldn’t be worth anything. My own favorite example of a satire that everyone misinterpreted, foes and friends alike, is Daniel Defoe’s Shortest Way with Dissenters. Defoe was a Dissenter (or Puritan), and his essay about how Dissenters should be tortured—he was satirizing unjust practices against them—was praised by hostile Anglicans and attacked by his fellow Dissenters. When it was discovered that the article was satirical, Defoe was placed in the pillory.

You can go here if you want to learn more about Carl, including how he left a software engineering job to teach high school and how he recently won a prestigious state teaching award. On top of that, he just learned Friday that he has also won the PLATO (Philosophy Learning and Teaching Organization) national award for high school teaching.

By Carl Rosin, English teacher, Radnor High School

The Internet, that cauldron wherein outrage-soup is stewed daily, has served up a spicy bowl of accusation to satirist Stephen Colbert and Comedy Central, the network that hosts his Colbert Report. Commentators from all corners quickly re-entrenched themselves in established positions about various political alignments, racism, white privilege, victimization, Twitter, censorship, and offensiveness, but perhaps the most intriguing commentary to have come from this is that which reflects on the noble, storied act of committing satire.

Colbert’s Wednesday show featured a bit (the third part in the linked-to segment) mocking the Washington NFL team and its owner Daniel Snyder, who has started a foundation designed to benefit American Indians. The satire used the fact that Snyder’s generosity may help improve his team’s image during the ongoing controversy about the racist team name, while pointing out how Snyder unapologetically perpetuates the racist name itself. Colbert juxtaposed his commentary on Snyder with a reference to his own offensive character, an outrageously hyperbolic Asian stereotype named Ching-Chong Ding-Dong, and constructed an analogous foundation. The bit was edgy, to say the least, leaning deeply into offensive stereotyping to satirize other offensive stereotyping.

Comedy Central inadvertently (I think) ratcheted up a controversy the next day when its Twitter feed promoted Colbert’s punchline without the full satirical context, tweeting, “I am willing to show #Asian community I care by introducing the Ching-Chong Ding-Dong Foundation for Sensitivity to Orientals or Whatever.” Activist Suey Park exploded upon seeing what appeared to be a racist blurb, blasting out a “CancelColbert” hashtag that was clearly intended to hold Colbert to account for his offensive approach. Others, like Brittney Cooper at Time.com, followed up in a similar vein.

My first thought: ask Mark Twain to comment.

Satire is an exalted literary form, with a noble history of communicating difficult ideas in insidiously persuasive ways. As Prof. Bates has often noted, here and via Prof. Ben Click here and in many other related posts, a literary satire like Adventures of Huckleberry Finn both gains power and incurs risk by developing the ironic gap between its literal level and the level of design or intent. Few novels have been banned as often as Huck, and few have incurred more vitriol. At the same time, few have earned more praise, and few have more power.

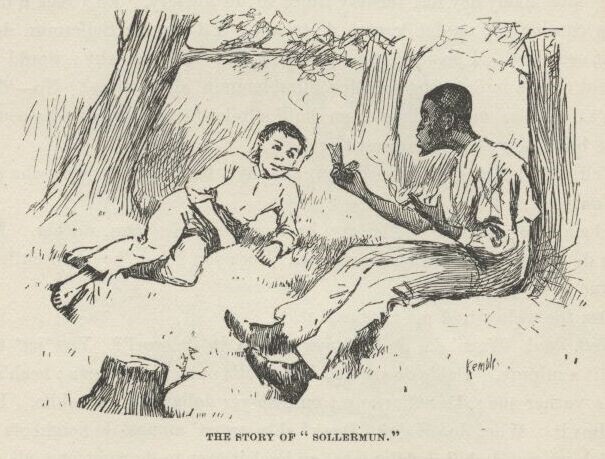

An example from the novel that illuminates this is chapter XIV’s argument between Huck and Jim, which culminates in their disagreement about whether King Solomon was wise. Huck, despite his love of freedom and his incessant resistance to authority, has started to internalize what society has to say: his first claim in favor of King Solomon’s wisdom is that the widow Douglas told him Solomon was wise. We readers whiff danger, knowing as we already do about the virulence of conformity within the corrupted slaveholding society in which Huck was raised.

Jim protests that some of Solomon’s famous exploits don’t show wisdom at all, and the two go back and forth about whether the famous splitting-the-baby episode proves the king to have been clever to have devised a solution (Huck) or barbaric even to suggest it (Jim). Huck cannot convince Jim, and Jim cannot convince Huck. The scene cleverly and subtly portrays the uneducated slave as a person of compassion who is capable of constructing a viewpoint that responsibly challenges conventional wisdom about the Bible – a conventional wisdom that Twain loved to tweak. Huck, exasperatedly unable to recognize any value in Jim’s position, ends the scene by saying, “I see it warn’t no use wasting words – you can’t learn a nigger to argue. So I quit.” Woe to us all if we “quit” challenging entrenched perspectives. Twain’s satire has dug a foundation for the novel’s developing challenge to racism.

Imagine, however, Twain’s publisher sending out a tweet to plump for that chapter. The tweet says only, “I see it warn’t no use wasting words – you can’t learn a n***** to argue.” (Update: I wrote this post before seeing Colbert make essentially this same point in his Monday night show, only he imagined someone sending out a passage from Swift’s “Modest Proposal.”)

Even in context, the chapter is challenging, edgy, many might say offensive. Out of context, it’s wildly inflammatory.

Commentators wise and foolish have all brought up the power of context in the Colbert/Snyder/Park situation. Colbert’s defenders on Deadspin and elsewhere opined fiercely that readers had to consider context or else satire makes no sense, or, even worse, it often seems to make “sense” that is the opposite of its designed intent.

Several defenders seemed to start, interestingly enough, from the context that Colbert has had such an impressive history of skewering racism that he deserves the benefit of the doubt, which pushes us to consider the double standard that Bill Maher pointed out this week in comparing statements by Paul Ryan (who tends not to get the benefit of the doubt, thanks to his record) and Michelle Obama (who does, thanks to hers). Several of the articles on the flap feature reader comments that say that the team name is not racist at all, because it is in the context of a proud, 77-year football tradition. Someone invariably brings up the difference between the use of the “n-word” by African-American and non-African-American speakers. I don’t agree that those latter two cases are equivalent, by the way, but both scream to us about how much context matters.

A novel, unlike the Internet, demands sustained attention and careful consideration. It is a world into which the reader embeds herself or himself. Some satires may be briefer, but any satire’s ethos must be established before its intent can be judged reasonably. To call “Satire!” is not to give an airtight excuse, though; poorly targeted satire simply fails, which thoughtful readers have the right to evaluate. In fact, as much as I love Colbert as a satirist – he is arguably the best one going today, with all due respect to other brilliant purveyors like Jon Stewart and Andy Borowitz – I find his original Ching-Chong Ding-Dong (the 2005 clip embedded in last week’s show) painful to watch, and I consider that an example of a rare failure for him.

My interdisciplinary Viewpoints on Modern American class of 30 high school juniors recently discussed literary tragedy in the context of Arthur Miller’s Death of a Salesman. Willy Loman’s suicide evokes powerful, conflicting feelings, providing a culmination of the pity and fear that Aristotle asserts that we audience members feel upon witnessing a tragic circumstance. I asserted that suicide in literature tends to be more about life than death, but for the many of us who have been touched by a suicide in some way, we may struggle to distance the concept from the literal instance of an individual taking his or her own life.

Catharsis is a powerful tool in comedy, as it is in tragedy. My teaching partner raised the concept of “too soon,” referring to Gilbert Gottfried’s ill-fated attempt to joke about 9/11 back in 2001. Taboos and the act of giving or withholding permission play powerful roles in our public discourse. Some topics, like slavery or rape, may always be off-limits to some people. The conversation about them is itself illuminating, even as it often raises welts. Distance runners and people who identify strongly with Boston tend to react more viscerally than the general public do to last year’s bombing, and will be more deeply affected by the upcoming anniversary of that devastation; for Jews like me it tends still to be “too soon” to joke casually about the Holocaust. Individuals relate to narrative in ways constructed by the author but which are also deeply informed and affected by their personal experience and position. The modernists and post-modernists might say that we must be wary of fooling ourselves about the pre-eminence and inviolability of Text.

But, as Better Living Through Beowulf has pointed out in dozens of insightful ways over the years, literature is essentially about empathy, profoundly and unrelentingly. Is it possible to make an evaluation on a normative level about the suitability and effectiveness of a satire while also addressing the fact that individuals may perceive that in a highly offensive – and thus unsuitable, ineffective – way?

Were our great writers afraid of offending, the bar would be set too low for literature to perform its sacred ministrations. Stephen Colbert may not be perceived as literature, but his satire is part of an invaluable tradition. We protect it by putting more of the onus on ourselves, the readers and viewers, instead of letting our viscera spill out.

That being said, however, we also do a disservice to all readers when we demand that they distance themselves far enough from the blast zone that they not feel personal hurt. That disservice smacks of imperialism. Literature’s task, therefore, is to keep contact with both shores, in a dialectic that is impossible to simplify.

Is satire, and arguably any edgy piece of literature, ever truly safe? No, and that’s why we need it.