I’ve been saving a Pelagia Horgan New Yorker article on “crying while reading” for a while, but now is a good time to share it as we are studying “the Age of Sensibility” in my Couples Comedy class. Comedy, to be sure, is generally seen as opposed to sensibility, a contrast of the head and the heart. Mixed together, however, comedy and romance become a potent genre, as we well know from our romantic comedies. One sees various 18th century authors, including Jane Austen, exploring the possibilities. (I end the course with Sense and Sensibility.)

I begin my course with Restoration comedies of the late 17th century in which one finds very little sentiment. That’s because Charles II’s English was still a very formal society with little interest in people “spilling their guts.” After all, as that revealing phrase suggests, to be emotional is to be vulnerable. I pointed out to my students that Hobbes’ theory of laughter reigned at the time and, in Hobbes’ vision, to be vulnerable is to be dead.

Vulnerability would become something positive in the 18th century, however, with French philosophe Jean Jacques Rousseau leading the way. In works like Julie, or the Nouvelle Héloise and Confessions, the French philosophe championed the softer emotions. “I feel, therefore I am” was essentially Rousseau’s response to the Age of Reason.

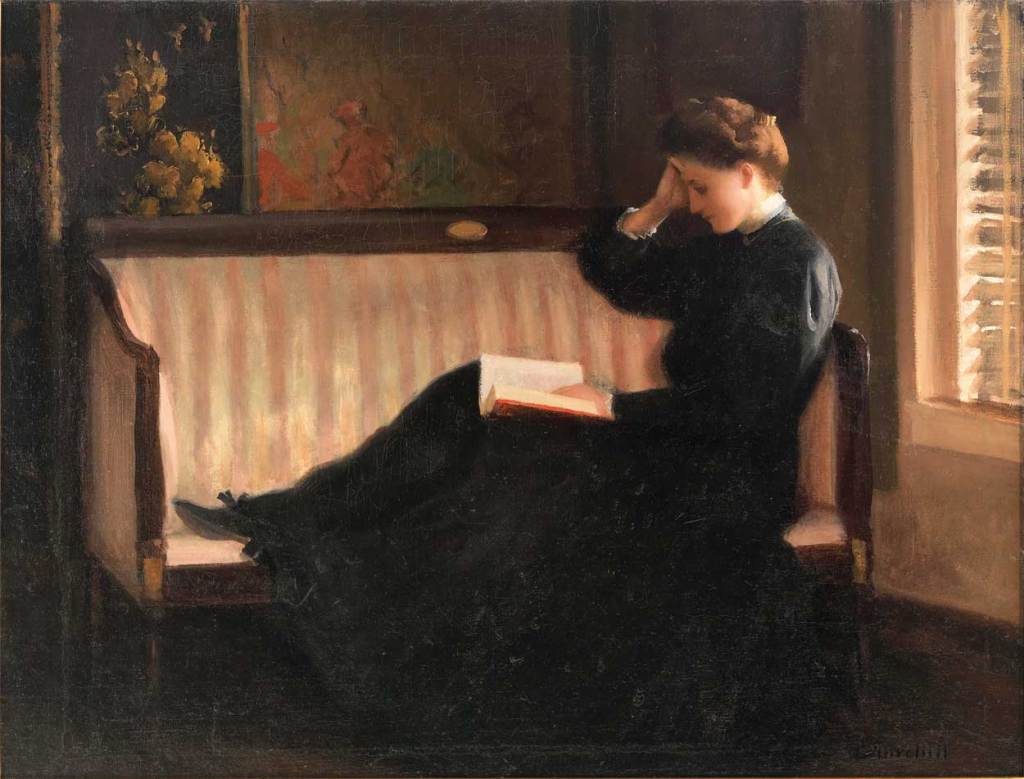

The New Yorker piece talks about Clarissa, Samuel Richardson’s million-word epistolary novel that disrupted households all over England as women neglected their chores and retired to their “closets” (small rooms) to bathe in the travails of kidnapped Clarissa Harlowe. Horgan quotes a fan letter written to Richardson by one Lady Bradshaigh:

I verily believe I have shed a pint of tears, and my heart is still bursting, tho’ they cease not to flow at this moment, nor will, I fear, for some time … in agonies would I lay down the book, take it up again, walk about the room, let fall a flood of tears, wipe my eyes, read again, perhaps not three lines, throw away the book, crying out, excuse me, good Mr. Richardson, I cannot go on.

Some kind of peak was reached in 1771 with the publication of Henry MacKenzie’s novel Man of Feeling. In one later edition of the book, available on-line, an editor counted 47 passages with tears in them, and that’s not including the passages where people are choked up. (The on-line version helpfully has links to all 47.) Here’s a sampling:

The desperation that supported her was lost; she fell to the ground, and bathed his feet with her tears.

Harley undertook her cause: he related the treacheries to which she had fallen a sacrifice, and again solicited the forgiveness of her father. He looked on her for some time in silence; the pride of a soldier’s honour checked for a while the yearnings of his heart; but nature at last prevailed, he fell on her neck and mingled his tears with hers.

Of course, wherever there is a new trend, there is a reaction. Older people and traditionalists were suspicious of the new craze for expressing feelings, and one also saw a sincerity crisis where people faked tender feelings in order to manipulate others. Richard Sheridan captured this in School for Scandal, where the villain, Joseph Surface, poses as a “man of sentiment.” But despite the reaction, sentiment was here to stay, and Horgan’s article tracks it through the 19th century and into the 20th. For instance:

In the nineteenth century, the meaning of tears evolved in two divergent directions. Some writers sought to provoke ever more “elevated” feelings in their readers: Victorian sentimentalists wrote tear-inducing scenes, often centered on the death of a child, in an effort to inspire social and political reform. (Think of Dickens, or Harriet Beecher Stowe.) Other writers embraced the idea of an “addiction” to emotion. The “sensation” novel, a different type of Victorian best-seller, showed that tears could be enjoyable in themselves. Sensation novels were the forerunners of the modern thriller, mystery, and tearjerker; heavy on adultery, blackmail, bigamy, secrets, madness, and melodramatic twists and revelations, they were known for creating physical “sensations” in their readers— goosebumps, shivers, a pounding heart, and, in melodramas such as Ellen Wood’s “East Lynne,” tears. But these were tears without moral purpose or effect: sensation for sensation’s sake. Reviewers found the novels distasteful; readers bought them in droves.

In my couples comedy class, I talked yesterday about how Tom Jones, one of literature’s comic masterpieces, also has a heavy dose of sentiment. The touch of a baby’s hand, for instance, outweighs for Allworthy any arguments against sending the child away. We’ll be looking at the mixture of sentiment and comedy in Fanny Burney’s Evelina and also in Austen’s Sense and Sensibility. In the latter work, Austen is concerned about the overly sentimental Marianne, who comes close to ruin and close to death because of the way she throws herself into affairs of the heart. But because she learns to balance sensibility with sense, there is a happy ending, and along the way there are some fairly humorous jabs at her sensitivity, such as Elinor noting that her rapturous conversations with Willoughby about the romantic poetry of William Cowper means that they’re rapidly going to run out of things to say.

Although there are exceptions, for the most part the 19th century didn’t exhibit the comic genius that the 18th century did, in part because it was so invested in a literature of feeling. But it did end with the brilliantly comic Oscar Wilde, who memorably mocked Dickens’ conclusion to The Old Curiosity Shop, which had readers everywhere sobbing.

‘One would have to have a heart of stone,” he wrote, “to read the death of little Nell without dissolving into tears…of laughter.”

Sometimes the heart wins, sometimes the head, and sometimes they find a way to work together.