Spiritual Sunday

I find today’s Gospel reading (John 10:1-10) particularly vivid because I know it by two of the literary passages it influenced, one in Paradise Lost, the other in C.S. Lewis’s Magician’s Nephew. In the reading Jesus compares false prophets to thieves:

“Very truly, I tell you,” Jesus says, “anyone who does not enter the sheepfold by the gate but climbs in by another way is a thief and a bandit. The gatekeeper opens the gate for him, and the sheep hear his voice.

When the disciples don’t get the analogy, Jesus elaborates:

Very truly, I tell you, I am the gate for the sheep. All who came before me are thieves and bandits; but the sheep did not listen to them. I am the gate. Whoever enters by me will be saved, and will come in and go out and find pasture. The thief comes only to steal and kill and destroy. I came that they may have life, and have it abundantly.

In Paradise Lost, Satan is the thief, climbing over the fence surrounding the Garden of Eden to steal away Adam and Eve. Being an angel, however, he bounds rather than climbs:

One Gate there only was, and that looked East On th' other side: which when th' arch-felon saw Due entrance he disdained, and in contempt, At one slight bound high over leap'd all bound Of Hill or highest Wall, and sheer within Lights on his feet. As when a prowling wolf, Whom hunger drives to seek new haunt for prey, Watching where shepherds pen their flocks at eve In hurdled Cotes amid the field secure, Leaps o'er the fence with ease into the fold: Or as a thief bent to unhoard the cash Of some rich burgher, whose substantial doors, Cross-barred and bolted fast, fear no assault, In at the window climbs, or o'er the tiles; So climbed this first grand Thief into God’s Fold: So since into his Church lewd Hirelings climb. Thence up he flew, and on the Tree of Life, The middle Tree and highest there that grew, Sat like a Cormorant; yet not true Life Thereby regaind, but sat devising Death To them who lived…

Milton uses the same passage to go over the Church’s “lewd Hirelings” in the final book. The angel Michael is telling Adam what the future holds once the Jesus’s apostles are no longer around to spread the message:

Wolves shall succeed for teachers, grievous Wolves,

Who all the sacred mysteries of Heaven

To their own vile advantages shall turn

Of lucre and ambition,

Milton’s comparison of Satan to a cormorant in the Eden episode accounts for the otherwise unexplained bird that appears in Lewis’s book. Aslan has sent Digory to retrieve an apple that will be planted so that the tree can protect the newly-created Narnia. The details from Jesus’s analogy are all present, including the gate. This one bears an inscription:

Come in by the gold gates or not at all,

Take of my fruit for others or forbear.

For those who steal or those who climb my wall

Shall find their heart's desire and find despair.

Digory wonders why anyone would climb when there’s a gate, which is Jesus’s message:

“Take of my fruit for others,” said Digory to himself. “Well, that’s what I’m going to do. It means I mustn’t eat any myself, I suppose. I don’t know what all that jaw in the last line is about. Come in by the gold gates. Well who’d want to climb a wall if he could get in by a gate! But how do the gates open?” He laid his hand on them and instantly they swung apart, opening inwards, turning on their hinges without the least noise.

When he finds the tree and plucks the apple, he is immediately confronted with temptation:

He knew which was the right tree at once, partly because it stood in the very center and partly because the great silver apples with which it was loaded shone so and cast a light of their own down on the shadowy places where the sunlight did not reach. He walked straight across to it, picked an apple, and put it in the breast pocket of his Norfolk jacket. But he couldn’t help looking at it and smelling it before he put it away.

It would have been better if he had not. A terrible thirst and hunger came over him and a longing to taste that fruit. He put it hastily into his pocket; but there were plenty of others. Could it be wrong to taste one? After all, he thought, the notice on the gate might not have been exactly an order; it might have been only a piece of advice—and who cares about advice? Or even if it were an order, would he be disobeying it by eating an apple? He had already obeyed the part about taking one “for others.”

At this point he encounters the bird:

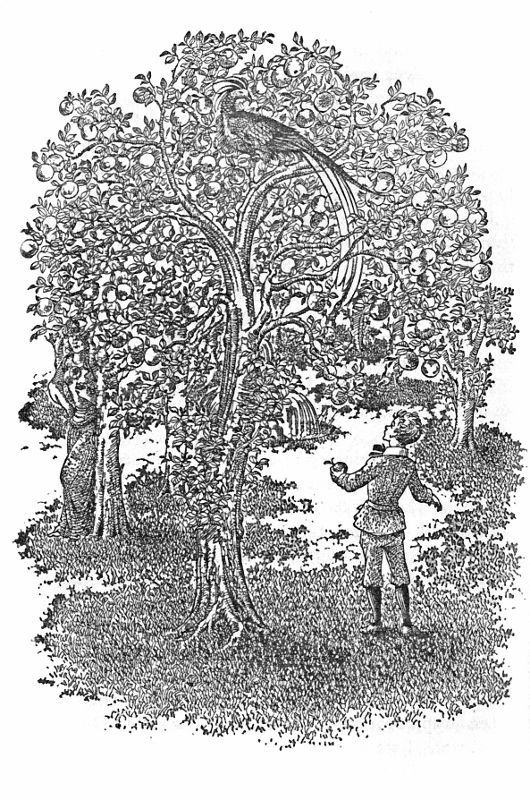

While he was thinking of all this he happened to look up through the branches towards the top of the tree. There, on a branch above his head, a wonderful bird was roosting. I say “roosting” because it seemed almost asleep: perhaps not quite. The tiniest slit of one eye was open. It was larger than an eagle, its breast saffron, its head crested with scarlet, and its tail purple.

“And it just shows,” said Digory afterwards when he was telling the story to the others, “that you can’t be too careful in these magical places. You never know what may be watching you.” But I think Digory would not have taken an apple for himself in any case. Things like Do Not Steal were, I think, hammered into boys’ heads a good deal harder in those days than they are now. Still, we can never be certain.

The bird in this instance appears to be operating as a superego rather than a Satanic id. Digory sees himself from the outside and that stiffens his resolve–which is fortunate since, at that point, he encounters the Witch Jadis, who has fled upon their encounter with Aslan. In Magician’s Nephew as in The Silver Chair, Lewis problematically conflates women and serpents, Eve and the snake. The red stain around Jadis’s mouth suggests carnality:

Digory was just turning to go back to the gates when he stopped to have one last look round. He got a terrible shock. He was not alone. There, only a few yards away from him stood the Witch. She was just throwing away the core of an apple which she had eaten. The juice was darker than you would expect and had made a horrid stain round her mouth. Digory guessed at once that she must have climbed in over the wall. And he began to see that there might be some sense in that last line about getting your heart’s desire and getting despair along with it. For the Witch looked stronger and prouder than ever, and even, in a way, triumphant: but her face was deadly white, white as salt.

Jadis tempts him, first by offering him immense power and immortal life and then, when that doesn’t work, invoking his seriously-ill mother:

“But what about this Mother of yours whom you pretend to love so?”

“What’s she got to do with it?” said Digory.

“Do you not see, Fool, that one bite of that apple would heal her? You have it in your pocket. We are here by ourselves and the Lion is far away. Use your Magic and go back to your own world. A minute later you can be at your Mother’s bedside, giving her the fruit. Five minutes later you will see the colorr coming back to her face. She will tell you the pain is gone. Soon she will tell you she feels stronger. Then she will fall asleep—think of that; hours of sweet natural sleep, without pain, without drugs. Next day everyone will be saying how wonderfully she has recovered. Soon she will be quite well again. All will be well again. Your home will be happy again. You will be like other boys.”

“Oh!” gasped Digory as if he had been hurt, and put his hand to his head. For he now knew that the most terrible choice lay before him.

Digory resists temptation, however, and in the end saves both his honor and his mother. Aslan, however, makes it clear that, had Digory taken the Witch’s power path, both he and his mother would have paid a price:

“I—I nearly ate one myself, Aslan,” said Digory. “Would I——”

“You would, child,” said Aslan. “For the fruit always works—it must work—but it does not work happily for any who pluck it at their own will…And the Witch tempted you to do another thing, my son, did she not?”

“Yes, Aslan. She wanted me to take an apple home to Mother.”

“Understand, then, that it would have healed her; but not to your joy or hers. The day would have come when both you and she would have looked back and said it would have been better to die in that illness.

The way to Heaven—or to Heaven on earth—is letting God rather than your ego guide your life.